![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

78 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

Sudden sharp pain in the pelvis that becomes more generalised indicates |

rupture of an ectopic pregnancy or an ovarian cyst.

BE ECTOPIC MINDED |

|

|

Recurrent sharp self-limiting pain indicates |

ruptured Graafian follicle (mittelschmerz). |

|

|

A UK study1 of chronic lower abdominal pain in women showed the causes were |

adhesions (36%), no diagnosis (19%), endometriosis (14%), constipation (13%), ovarian cysts (11%) and PID (7%). An Australian study found that endometriosis accounted for 30% and adhesions 20% |

|

|

Why is their refered pain to lower back, buttocks and post. thigh? |

The principal afferent pathways of the pelvic viscera arise from T10–12, L1 and S2–4. Thus disorders of the bladder, rectum, lower uterus, cervix and upper vagina can refer pain to the low back, buttocks and posterior thigh. |

|

|

Probability diagnosis of lower abdo pain |

primary dysmenorrhoea, ruptured Graafi an follicle (mittelschmerz), endometriosis adhesions unknown |

|

|

Serious disorders not to be missed |

ruptured ectopic pregnancy PID neoplasm

|

|

|

Pitfalls |

haeommrage into the ovary torsion of ovary pedunculated fibroid constipation |

|

|

7 masqerades checklist |

UTIs spinal dysfunction |

|

|

Acute pain |

ectopic acute PID rupture or torsion of ovarian cyst acute appendix |

|

|

Chronic pain |

endometriosis, PID, an ovarian neoplasm and the irritable bowel syndrome.

|

|

|

Pelvic congestion syndrome |

- ovarian dysfn (similar to PCOS) with variable congestion |

|

|

Pelvic congestion syndrome clincal features |

Clinical features • Patient usually para 3 or 4 • Typical age 35–40 years • Unilateral pain, increased with standing and walking • Relief with lying down • Deep dyspareunia • Postcoital aching |

|

|

Ectopic pregnancy occurence rate |

1in 100 - rupture can be fatal rapidly |

|

|

Commonest cause of intraperitoneal haemorrhage |

ectopic pregnacy |

|

|

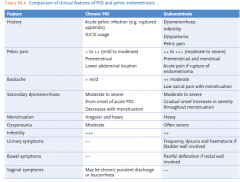

Differences between PID and endometriosis |

|

|

|

Clincal features of a ruptures ectopic pregnancy |

• Average patient in mid-20s • First pregnancy in one-third of patients • Pre-rupture symptoms (many cases): — abnormal pregnancy — cramping pains in one or other iliac fossa — vaginal bleeding • Rupture: — excruciating pain (see Fig. 94.2) — circulatory collapse Note: In 10–15% there is no abnormal bleeding. • Pain may radiate to rectum (lavatory sign), vagina or leg • Signs of pregnancy (e.g. enlarged breasts and uterus) usually not present |

|

|

RF for ectopic pregnancy |

— previous ectopic pregnancy — previous PID — previous abdominal or pelvic surgery, especially sterilisation reversal — IUCD use — in-vitro fertilisation/GIFT |

|

|

amenorrhoea (65–80%) + lower abdominal pain (95+%) + abnormal vaginal bleeding (65–85%) = |

ectopic pregancy |

|

|

Examinations results of an ectopic |

• Deep tenderness in iliac fossa • Vaginal examination: — tenderness on bimanual pelvic examination (pain on cervical provocation) — soft cervix • Bleeding (prune juice appearance) • Temperature and pulse usually normal early |

|

|

Diagnosis of an ectopic |

• Urine pregnancy test (positive in <50%) • Serum β-HCG assay >1500 IU/L (invariably positive if a signifi cant amount of viable trophoblastic tissue present)—may need serial quantitative tests to distinguish an ectopic from a normal intra-uterine pregnancy. If <1000 IU/L repeat every second day • Transvaginal ultrasound can diagnose at 5–6 weeks (empty uterus, tubal sac, fl uid in cul-de-sac) • Laparoscopy (the defi nitive diagnostic procedure) |

|

|

Mx of an ectopic |

This is a time-critical emergency. Organise blood and contacts, resuscitate as necessary. Treatment may be conservative (based on ultrasound and β-HCG assays); medical, by injecting methotrexate into the ectopic sac; laparoscopic removal; or laparotomy for severe cases. Rupture with blood loss demands urgent surgery. |

|

|

Post managment of an ectopic what are the chances of successful pregnancy vs subsequent ectopics |

• Successful pregnancy 60–65% • Subsequent risk of ectopic pregnancy 10–15% |

|

|

Ruptured ovarian (Graafian) follicle (mittelschmerz) |

When the Graafi an follicle ruptures a small amount of blood mixed with follicular fl uid is usually released into the pouch of Douglas. This may cause peritonism (mittelschmerz), which is different from the unilateral pain experienced just before ovulation due to distension of the ovarian capsule. |

|

|

Clinical features of a ruptured ovarian follicle |

• Onset of pain in mid-cycle • Deep pain in one or other iliac fossa (RIF > LIF) • Often described as a ‘horse kick pain’ • Pain tends to move centrally (see Fig. 94.3) • Heavy feeling in pelvis • Relieved by sitting or supporting lower abdomen • Pain lasts from a few minutes to hours (average 5 hours) • Patient otherwise well Note: Sometimes it can mimic acute appendicitis. |

|

|

Mx of ruptured ovarian follicle |

• Explanation and reassurance • Simple analgesics: aspirin or paracetamol • ‘Hot water bottle’ comfort if pain severe |

|

|

Types of ovarian neoplasms |

ovatian cysts |

|

|

Ovarian Cysts |

- may be assymptomatic but will cause pain if complicated - common <50yrs - defined on vaginal ultrasound |

|

|

Ovarian tumours Sx |

• Pain (usually torsion or haemorrhage) • Pressure symptoms • Menstrual irregularity |

|

|

Ruptured ovarian cyst Clinically |

- occurs after coitus or prior to ovulation • Patient usually 15–25 years • Sudden onset of pain in one or other iliac fossa • May be nausea and vomiting • No systemic signs • Pain usually settles within a few hours |

|

|

Examination signs of ruptured ovarian cyst |

• Tenderness and guarding in iliac fossa • PR: tenderness in rectovaginal pouch |

|

|

Investigating a ruptured ovarian cyst |

• Ultrasound ± colour Doppler (for enhancement) |

|

|

Mx a ruptured ovarian cyst |

• Appropriate explanation and reassurance • Conservative: — simple cyst <4 cm — internal haemorrhage — minimal pain • Needle vaginal drainage by ultrasonography for a simple larger cyst • Laparoscopic surgery: — complex cysts — large cysts — external bleeding |

|

|

Acute torsion of ovarian cyst pathophysiology |

Torsions are mainly from dermoid cysts and, when right-sided, may be diffi cult to distinguish from acute pelvic appendicitis. |

|

|

Acute torsion of ovarian cyst clincally |

• Severe cramping lower abdominal pain • Diffuse pain • Pain may radiate to the fl ank, back or thigh • Repeated vomiting • Exquisite pelvic tenderness • Patient looks ill |

|

|

Signs of acute torsion of ovarian cyst |

• Smooth, rounded, mobile mass palpable in abdomen • May be tenderness and guarding over the mass, especially if leakage |

|

|

Tx of acute torsion of ovarian cyst |

laparotomy and surgical correction |

|

|

Malignant ovarian tumours incidence |

1 in 1000 cases 5% of cancers in women peaks 60-65 years (up fro 45) |

|

|

Prognosis of ovarian tumours |

most gynaecological deaths because usually well advanced before clinical presentation |

|

|

RF for ovarian cancer |

age family hx nulliparity |

|

|

Protective factors for ovarian cancer |

pregancy COC |

|

|

Clinical features of ovarian cancer |

• Constitutional symptoms: fatigue, anorexia • Ache or discomfort in lower abdomen or pelvis • Abdominal bloating and ‘fullness’ • Gastrointestinal dysfunction (e.g. epigastric discomfort, diarrhoea, constipation, wind) • Sensation of pelvic heaviness • Genitourinary symptoms (e.g. frequency, urgency, prolapse) • ± Abnormal uterine bleeding • Postmenopausal bleeding • Dyspareunia and/or dysmenorrhoea (10–20%) • A combined vaginal–rectal bimanual examination assists diagnosis. Look for mass, ascites, pleural effusion • ±Weight loss Note: Any ovary that is easily palpable is usually abnormal (normal ovary rarely >4 cm). |

|

|

Dx ovarian cancer |

• Ultrasound ± colour Doppler • Tumour markers such as CA-125, β-HCG (choriocarcinoma) and alpha-fetoprotein are becoming more important in diagnosis and management Refer urgently to gynaecologist. |

|

|

Dysmennorrhoea |

primary is from the onset of mensese (menarche) secondary is when it starts later on in life |

|

|

Primary Dysmenorrhoea affects _____ % of when and starts within ____ years till ____ years old |

commences within 1–2 years after the menarche and becomes more severe with time up to about 20 years. It affects about 50% of menstruating women and up to 95% of adolescents |

|

|

Clincal features of 1o dysmenorrhoea |

• Low midline abdominal pain • Pain radiates to back or thighs (see Fig. 94.5) • Varies from a dull dragging to a severe cramping pain • Maximum pain at beginning of the period • May commence up to 12 hours before the menses appear • Usually lasts 24 hours but may persist for 2–3 days • May be associated with nausea and vomiting, headache, syncope or fl ushing • No abnormal fi ndings on examination |

|

|

Mx of primary dysmenorrhea - lifestyle |

• Full explanation and appropriate reassurance • Promote a healthy lifestyle: — regular exercise — avoid smoking and excessive alcohol • Recommend relaxation techniques such as yoga • Avoid exposure to extreme cold • Place a hot water bottle over the painful area and curl the knees onto the chest |

|

|

Mx of 1o dysmenorrhea Medications |

• simple analgesics (e.g. aspirin or paracetamol) • prostaglandin inhibitors (e.g. mefenamic acid 500 mg tds) or NSAIDs (e.g. naproxen, ibuprofen 200–400 mg (o) tds) at fi rst suggestion of pain (if simple analgesics ineffective) • Vitamin B1 (thiamine) 100 mg daily • COC (low-oestrogen triphasic pills preferable) • progestogen-medicated IUCD |

|

|

Cochrane review of effectiveness of meds |

A Cochrane review found that the most beneficial medication was the NSAIDs, and also vitamin B1 and magnesium proved effective. There was no evidence so far that the vitamin B6, vitamin E or herbal remedies were effective. Spinal manipulation was unlikely to be benefi cial |

|

|

Secondary dysmenorrhoea |

Secondary dysmenorrhoea is menstrual pain for whichan organic cause can be found. It usually begins after the menarche after years of pain-free menses; the patient is usually over 30 years of age. The pain begins as a dull pelvic ache 3–4 days before the menses and becomes more severe during menstruation. |

|

|

Commonest causes of secondary dysmenorrhoea |

• endometriosis (a major cause) • PID (a major cause) • IUCD • submucous myoma • intra-uterine polyp • pelvic adhesions |

|

|

Investigations into 2ndary Dysmenorrhoea |

laparoscopy, ultrasound and (less commonly) assessment of the uterine cavity by dilation and curettage, hysteroscopy or hysterosalpingography. |

|

|

Pelvic adesions |

Pelvic adhesions may be the cause of pelvic pain, infertility, dysmenorrhoea and intestinal pain. They can be diagnosed and removed laparoscopically when the adhesions are well visualised and there are no intestinal loops fi rmly stuck together. |

|

|

Endometriosis |

ectopically located endometrial tissue (usually in dependent parts of the pelvis and in the ovaries) responds to female sex hormone stimulation by proliferation, haemorrhage, adhesions and ultimately dense scar tissue changes. The average time to diagnosis is 10 years. The diagnosis is marked by taking NSAIDs and the COC |

|

|

Clincal features of endometriosis |

• 10% incidence7 • Puberty to menopause, peak 25–35 years • Secondary dysmenorrhoea • Infertility • Dyspareunia • Non-specifi c pelvic pain • Menorrhagia • Acute pain with rupture of endometrioma • Premenstrual spotting - dyschacexia |

|

|

dysmenorrhoea + menorrhagia + abdominal/pelvic pain = |

endometriosis |

|

|

dysmenorrhae + dyspareunia + dyschaexia |

endometriosis |

|

|

Signs on examining for endometriosis |

• Fixed uterine retroversion • Tenderness and nodularity in the pouch of Douglas/retrovaginal septum • Uterine enlargement and tenderness |

|

|

Adenomyosis |

Adenomyosis: this is endometriosis of the myometrium affecting the endometrial glands and stroma. The symptoms are similar to endometriosis plus an enlarging tender uterus. |

|

|

Differential dx of endometriosis |

- PID - ovarian cysts or tumours - uterine myomas |

|

|

Dx of endometriosis |

• Usually by direct visual inspection at laparoscopy (the gold standard) or laparotomy • Ultrasound scanning helpful |

|

|

Tx of endometrisosis |

• Careful explanation • Basic analgesics • Treatment can be surgical or medical Medical:8 To induce amenorrhoea (only two-thirds respond to drugs): — danazol (Danocrine)—current treatment of choice — COC: once daily continuously for about 6 months — progestogens (e.g. medroxyprogesterone acetate —Depo-Provera) or orally 10 mg bd for up to 6 months — GnRH analogues (e.g. goserelin, 3.6 mg SC implant every 28 days for up to 6 months, nafarelin) In young teenagers an initial trial of ovarian suppression may be tried. Surgical: Surgical measures depend on the patient’s age, symptoms and family planning. Laser surgery and microsurgery can be performed via either laparoscopy or laparotomy. |

|

|

PID serious consequences |

tubal obstruction, infertility and ectopic pregnancy |

|

|

PID can be ______ or ________. |

acute, which causes sudden severe symptoms, or chronic, which can gradually produce milder symptoms or follow an acute episode. Acute PID is a major public health problem and is the most important complication of STIs among young women. The majority are young (less than 25 years), sexually active women who are also nulliparous |

|

|

Clinical features ACUTE vs CHRONIC |

Acute PID • Fever ≥38°C • Moderate to severe lower abdominal pain Chronic PID • Ache in the lower back • Mild lower abdominal pain Both acute and chronic • Dyspareunia • Menstrual problems (e.g. painful, heavy or irregular periods) • Intermenstrual bleeding • Abnormal, perhaps offensive, purulent vaginal discharge • Painful or frequent urination |

|

|

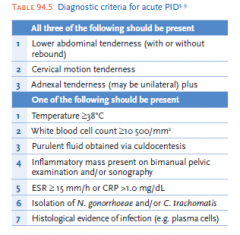

Diagnostic criteria for acute PID |

|

|

|

Examination of PID |

• In acute PID there may be lower abdominal tenderness ± rigidity. • Pelvic examination: in acute PID there is unusual vaginal warmth, cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness. Inspection usually reveals a red inflamed cervix and a purulent discharge. |

|

|

Causative agents in PID 3 groups |

1. Exogenous organisms 2. endogenous 3. actinomycosis |

|

|

Exogeneous PID causes |

: those which are community acquired and initiated by sexual activity. They include the classic STIs, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. This usually leads to salpingitis. |

|

|

Endogenous PID causes |

Endogenous infections: these are normal commensals of the lower genital tract, especially Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis. They become pathogenic under conditions that interrupt the normal cervical barrier, such as recent genital tract manipulation or trauma (e.g. abortion, presence of an IUCD, recent pregnancy or a dilatation and curettage). The commonest portals of entry are cervical lacerations and the placental site. These organisms cause an ascending infection and can spread direct or via lymphatics to the broad ligament, causing pelvic cellulitis |

|

|

Actinomycosis PID |

due to prolonged IUCD use. look for actinomyces israeli on culture |

|

|

Ix PID |

- definitive is laproscopy BUT hardly ever done

• Cervical swab for Gram stain and culture, PCR ( N. gonorrhoeae) • Cervical swab and special techniques (e.g. PCR for C. trachomatis) • Blood culture • Pelvic ultrasound |

|

|

Treatment of PID |

Any IUCD or retained products of contraception should be removed at or before the start of treatment. Sex partners of women with PID should be treated with agents effective against C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae |

|

|

Treating the STI in PID - mild to moderate infection |

azithromycin 1 g (o), as 1 dose plus (for gonorrhoea) ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or IV, as 1 dose plus (in all patients) doxycycline 100 mg (o) 12 hourly for 14 days plus either metronidazole 400 mg (o) 12 hourly for 14 days or tinidazole 500 mg (o) daily for 14 days |

|

|

Treating the STI in PID - severe infection |

Severe infection (treated in hospital): cefotaxime 1 g IV 8 hourly or ceftriaxone 1 g IV once daily plus doxycycline 100 mg (o) or IV 12 hourly plus metronidazole 500 mg IV 12 hourly until there is substantial clinical improvement, when the oral regimen above can be used for the remainder of the 14 days. If the patient is pregnant or breastfeeding, doxycycline should be replaced by roxithromycin 300 mg (o) daily for 14 days |

|

|

Treating infections that are non-sexually acquire due to gential manipulation (PID) |

Mild to moderate infection: amoxycillin + clavulanate (875 mg/125 mg) (o) 12 hourly for 14 days plus doxycycline 100 mg (o) 12 hourly for 14 days Severe infection (including septicaemia): use the same regimen as for severe sexually acquired infection. |

|

|

Actinomycosis Tx |

amoxycillin 500 mg tds + metronidazole 400 mg bd for 14 days. Ensure IUCD is removed |

|

|

When to refer |

• All cases of ‘unexplained infertility’ • All teenagers with dysmenorrhoea suffi cient to interfere with normal school, work or recreational activities, and not responding to prostaglandin inhibitors • Patients with dysmenorrhoea reaching a crescendo mid-menses • Patients with dysmenorrhoea and unexplained bowel or bladder symptoms • Patients with positional dyspareunia • Patients with cyclic pain or bleeding in unusual sites |

|

|

MOA of NSAIDs in dysmennorhea |

analgesic INHIBITS PGs |