![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

37 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

Where is Sherry Country located, in Spain?

|

(p322)

This winemaking region is situated in the province of Cádiz, around Jerez de la Frontera in the southwest of Spain. |

|

|

What is the climate like in Sherry Country?

|

(p322)

This is the hottest wine region in Spain. Generally, the climate is Mediterranean, but toward the Portugese border, the Atlantic influence comes into play and, farther inland, around Montilla-Moriles, it becomes more continental. It is the Atlantic-driven "poniente" wind that produces the flor yeast of fino sherry. |

|

|

What is the aspect of Sherry Country?

|

(p322)

Vines are grown on all types of land, from the virtually flat coastal plains producing manzanilla, through the slightly hillier sherry vineyards rising to 330 feet (100 meters), to the higher gentle inland slopes of Montilla-Moriles and the undulating Antequera plateau of Málaga at some 1,640 feet (500 meters). |

|

|

What is the soil like in Sherry Country?

|

(p322)

The predominant soil in Jerez is a deep lime-rich variety known as albariza, which soaks up and retains moisture. Its brilliant white color also reflects sun on to the lower parts of the vines. Sand and clay soils also occur but, although suitable for vine-growing, they produce second-rate Sherries. The equally bright soil to the east of Jerez is not albariza, but a schisto-calcareous clay. |

|

|

How important is vinification in Sherry Country?

|

Vinification is the key to the production of the great fortified wines for which this area is justly famous. Development of a flor yeast and oxidation by deliberately underfilling casks are vital components of the vinification, as, of course, is the solera system that ensures a consistent product over the years. The larger the solera the more efficient it is, because there are more butts. Montilla is vinified using the same methods as for sherry, but is naturally strong in alcohol, and so less often fortified.

|

|

|

What are the grape varieties in Sherry Country?

|

Grape Varieties in Sherry Country:

Palomino Pedro Ximénez Moscatel |

|

|

When did sherry regain exclusive use in Europe of its own name, which had suffered decades of abuse by producers of so-called "sherry" in other countries, especially Great Britain and Ireland?

|

On January 1, 1996. The governments of these countries had shamelessly vetoed the protection of sherry's name when Spain joined the Common Market in 1986. Such are the blocks and checks of the European Union (EU) that it took 10 years for this legislation, ensuring that the name sherry (also known as Jerez or Xèrés) may now be used only for the famous fortified wines made around Cádiz and Jerez de la Frontera in the south of Spain. Due to the sherry industry's own folly in trying to compete with these cheaper, fortified ripoffs, the vineyards of Jerez got into massive overproduction problems, but this was recognized in the early 1990s, when lesser-quality vineyards were uprooted, reducing the viticultural area from 43,000 acres (17,500 ha) to the current 26,000 acres (10,600 ha).

|

|

|

What is the history of wine production in sherry prior to the introduction of true sherry itself?

|

The vinous roots of sherry penetrate three millennia of history, back to the Phoenicians who founded Gadir (today called Cádiz), in 1100 BC. They quickly deserted Gadir because of the hot, howling levante wind that is said to drive people mad, and they established a town farther inland called Xera, which some historians believe may be the Xérès or Jerez of today. It was probably the Phoenicians who introduced viticulture to the region. If they did not, then the Greeks certainly did, and it was the Greeks who brought with them their hepsema, the precursor of the arropes and vinos de color that add sweetness, substance, and color to modern-day sweet or cream sherries. In the Middle Ages, the Moors introduced to Spain the alembic, a simple pot-still with which the people of Jerez were able to turn their excess wine production into grape spirit, which they added, along with arrope and vino de color, to their new wines each year to produce the first crude but true sherry.

|

|

|

How did the reputation of true sherry first spread?

|

The repute of these wines gradually spread throughout the Western world, helped by the English merchants who had established wine-shipping businesses in Andalucia at the end of the 13th century. After Henry VIII broke with Rome, Englishmen in Spain were under constant threat from the Inquisition. The English merchants were rugged individualists and they survived, as they also did, remarkably, when Francis Drake set fire to the Spanish fleet in the Bay of Cádiz in 1587. Described as the day he singed the King of Spain's beard, it was the most outrageous of all Drake's raids, and when he returned home, he took with him a booty of 2,900 casks of sherry. The exact size of these casks is not known, but the total volume is estimated to be in excess of 150,000 cases, which makes it a vast shipment of one wine for that period in history. It was, however, eagerly consumed by a relatively small population that had been denied its normal quota of Spanish wines during the war. England has been by far the largest market for sherry ever since.

|

|

|

Why is sherry from Spain so special?

|

It is the combination of Jerez de la Frontera's soil and climate that makes this region uniquely equipped to produce sherry, a style of wine attempted in many countries around the world but never truly accomplished outside Spain. Sherry has much in common with champagne, as both regions are inherently superior to all others in their potential to produce a specific style of wine. The parallel can be taken further: both sherry and champagne are made from neutral, unbalanced base wines that are uninspiring to drink before they undergo the elaborate process that turns them into high-quality, perfectly balanced, finished products.

|

|

|

What is the famous albariza soil of sherry made of?

|

Jerez's albariza soil, which derives its name from its brilliant white surface, is not chalk but a soft marl of organic origin formed by the sedimentation of diatom algae during the Triassic period.

|

|

|

What color is albariza soil?

|

While having a brilliant white surface, the albariza begins to turn yellow at a depth of about 3 feet (1 meter) and turns bluish after 16 feet (5 meters).

|

|

|

What are the properties of albariza soil?

|

It crumbles and is super-absorbent when wet, but extremely hard when dry. This is the key to the exceptional success of albariza as a vine-growing soil. Jerez is a region of baking heat and drought; there are about 70 days of rain each year, with a total precipitation of some 20 inches (50 centimeters). The albariza soaks up the rain like a sponge and, with the return of the drought, the soil surface is smoothed and hardened into a shell that is impermeable to evaporation. The winter and spring rains are imprisoned under this protective cap, and remain at the disposal of the vines, the roots of which penetrate some 13 feet (4 meters) beneath the surface. The albariza supplies just enough moisture to the vines, without making them too lazy or over-productive. Its high active-lime content encourages the ripening of grapes with a higher acidity level than would otherwise be the norm for such a hot climate. This acidity safeguards against unwanted oxidation prior to fortification.

|

|

|

What is the levante wind?

|

The hot, dry levante is one of Jerez de la Frontera's two alternating prevailing winds. This easterly wind blow-dries and vacuum-cooks the grapes on their stalks during the critical ripening stage. This results in a dramatically different metabolization of fruit sugars, acids, and aldehydes, which produces a wine with an unusual balance peculiar to Jerez.

|

|

|

What is the poniente wind?

|

Alternating with the levante is the wet Atlantic poniente wind. This is of fundamental importance, as it allows the growth of several Saccharomyces strains in the microflora of the Palomino grape. This is the poetically named sherry "flor," without which there would be no fino in Jerez.

|

|

|

What are sherry's classic grape varieties?

|

Palomino

Pedro Ximénez Moscatel Fino British sherry expert Julian Jeffs believes that as many as 100 different grape varieties were once traditionally used to make sherry and, in 1868, Diego Parada y Barreto listed 42 then in use. Today only three varieties are authorized: Palomino, Pedro Ximénez, and Moscatel Fino. The Palomino is considered the classic sherry grape and most sherries are, in fact, 100% Palomino, though they may be sweetened with Pedro Ximénez for export markets. |

|

|

What is the traditional method of harvesting grapes in sherry?

|

Twenty or more years ago, it was traditional to begin the grape harvest in the first week of September. After picking, Palomino grapes were left in the sun for 12-24 hours, Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel for 10-21 days. Older vines were picked before younger ones, and Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel were picked first of all because they required longer sunning than Palomino. At night, the grapes were covered with "esparto" grass mats as a protection against dew. This sunning is called the "soleo," and its primary purpose is to increase sugar content, while reducing the malic acid and tannin content. Although some producers still carry out the "soleo," most harvest in the second week of September and forgo the "soleo" for all grapes but Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel, used in the sweetest sherry. The grapes are now left in the sun for far fewer than the traditional 10-21 days.

|

|

|

What is "yeso"?

(Sherry) |

Traditionally, prior to pressing the grapes, the stalks are removed and a small proportion of "yeso" (gypsum) is added to precipitate tartrate crystals. This practice, which is dying out, may have evolved when growers noticed that grapes covered by albariza dust produced better wine than clean ones. Albariza has a high calcium carbonate content that would crudely accomplish the task.

|

|

|

What is the traditional method of pressing grapes in sherry?

|

Traditionally, four laborers called "pisadores" were placed in each "lagar" (open receptacle) to tread the grapes, not barefoot but wearing "zapatos de pisar," heavily nailed cowhide boots to trap the seeds and stalks undamaged between the nails. Each man tramped 36 miles (58 kilometers) in place during a typical session lasting from midnight to noon. Automatic horizontal, usually pneumatic, presses are now in common use.

|

|

|

What is the traditional method of fermentation in sherry?

|

Some sherry houses still ferment their wine in small oak casks purposely filled to only 90% capacity. After 12 hours, the fermentation starts and continues for between 36 and 50 hours at 77-86°F (25-30°C), by which time as much as 99% of available sugar is converted to alcohol; after a further 40 or 50 days, the process is complete. Current methods often use stainless-steel fermentation vats, and yield wines that are approximately 1% higher in alcohol than those fermented in casks due to an absence of absorption and evaporation.

|

|

|

What is the most traditional and most important sweetening agent in the production of sherry? How is it made?

|

Although gradually giving way to other less expensive ones, it is that made from pure, overripe, sun-dried Pedro Ximénez grapes, also known as PX. After the "soleo," or sunning, of the grapes, the sugar content of the PX increases from around 23% to between 43 and 54%. The PX is pressed and run into casks containing pure grape spirit. This process, known as muting, produces a mixture with an alcohol level of about 9% and some 430 grams of sugar per liter. This mixture is tightly bunged and left for four months, during which time it undergoes a slight fermentation, increasing the alcohol by about one degree and reducing the sugar by some 18 grams per liter. Finally, the wine undergoes a second muting, raising the alcoholic strength to a final 13% but reducing the sugar content to about 380 grams per liter.

|

|

|

Describe Moscatel, as a sweetening agent in sherry.

|

Moscatel:

This is prepared in exactly the same way as PX, but the result is not as rich and its use, which has always been less widespread than PX, is technically not permitted under DO regulations. |

|

|

What is "dulce pasa"?

|

Dulce Pasa:

Preparation is as for PX and Moscatel, but using Palomino, which achieves up to a 50% sugar concentration prior to muting. Its use is on the increase. This must not be confused with "dulce racimo" or "dulce apagado," sweetening agents that were once brought in from outside the region and are now illegal. |

|

|

What is "dulce de alimbar" or "dulce blanco"?

|

Dulce Alimbar, Dulce Blanco:

A combination of glucose and levulose blended with fino and matured, this agent is used to sweeten pale-colored sherries. |

|

|

What is "sancocho"?

|

A dark-colored, sweet, and sticky nonalcoholic syrup that is made by reducing unfermented local grape juice to one-fifth of its original volume by simmering over a low heat. It is used in the production of "vino de color" - a "coloring wine."

|

|

|

What is "arrope"?

|

This dark-colored, sweet, and sticky nonalcoholic syrup, made by reducing unfermented local grape juice to one-fifth of its original volume, is also used in the production of "vino de color."

|

|

|

What is "color de macetilla"?

|

Color de Macetilla:

This is the finest "vino de color" and is produced by blending two parts "arrope" or "sancocho" with one part unfermented local grape juice. This results in a violent fermentation and, when the wine falls bright, it has an alcoholic strength of 9% and a sugar content of 235 grams per liter. Prized stocks are often matured by "solera." |

|

|

What is "color remendado"?

|

Color Remendado:

This is a cheap, commonly used "vino de color," which is made by blending "arrope" or "sancocho" with local wine. |

|

|

How can you tell whether a cask will develop a good flor?

|

The larger bodegas like to make something of a mystery of the flor, declaring that they have no idea whether or not it will develop in a specific cask. There is some justification for this - one cask may have a fabulous froth of flor (looking like dirty soap suds), while the cask next to it may have none. Any cask with good signs of dominant flor will invariably end up as fino, but others with either no flor or ranging degrees of it may develop into one of many different styles. There is no way of guaranteeing the evolution of the wines, but it is well known that certain zones can generally be relied on to produce particular styles.

|

|

|

Which zones of sherry can generally be relied upon to produce particular styles of sherry?

|

(p322)

Typical Styles of Sherry Zones: Añina - fino Balbaina - fino Carrascal - oloroso Chipiona - Moscatel/sweet Los Tercios - fino Macharnudo - amontillado Madroñales - Moscatel/sweet Miraflores - fino/manzanilla Rota - Moscatel/sweet Sanlúcar - fino/manzanilla Tehigo - colouring wines Torrebreba - manzanilla |

|

|

What is flor?

|

For the majority of sherry drinkers, fino is the quintessential sherry style. It is a natural phenomenon called flor that determines whether or not a sherry will become a fino. Flor is a strain of Saccharomyces yeast that appears as a gray-white film floating on a wine's surface, and it occurs naturally in the microflora of the Palomino grape grown in the Jerez district. It is found to one degree or another in every butt or vat of sherry and manzanilla, but whether or not it can dominate the wine and develop as a flor depends upon the strength of the Saccharomyces and the biochemical conditions. The effect of flor on sherry is to absorb remaining traces of sugar, diminish glycerine and volatile acids, and greatly increase esters and aldeydes.

|

|

|

What does flor require in order to flourish?

|

For flor to flourish, it requires:

An alcoholic strength of between 13.5 and 17.5%. The optimum is 15.3%, the level at which vinegar-producing acetobacter is killed. A temperature of between 59 and 86°F (15 and 30°C). A sulfur dioxide content of less than 0.018%. A tannin content of less than 0.01%. A virtual absence of fermentable sugars. |

|

|

Describe the cask classification and fortification of sherry.

|

The cellarmaster's job is to sniff all the casks of sherry and mark on each one in chalk how he believes it is developing, according to a recognized cask-classification system. At this stage, lower-grade wines (those with little or no flor) are fortified to 18% to kill any flor, thus determining their character once and for all and thereafter protecting the wine from the dangers of acetification. The flor itself is a protection against the acetobacter that threaten to turn the wine into vinegar, but it is by no means invincible and will be at great risk until it is fortified to 15.3%, or above, the norm for fino, and is not truly safe until it is bottled.

|

|

|

What is usually used for the fortification of sherry?

|

A fifty-fifty mixture known as "mitad y mitad," "miteado," or "combinado" (half pure alcohol, half grape juice) is usually used for fortification. However, some producers prefer to use mature sherry for fortification instead of grape juice.

|

|

|

What further cask classification takes place in sherry?

|

The wines are often racked prior to fortification, and always after. Two weeks later, they undergo a second, more precise classification, but no further fortification, or other action, will take place until nine months have elapsed, after which they will be classified regularly over a period of two years to determine their final style.

|

|

|

What is the solera blending system?

|

Once the style of a sherry has been established, the wines are fed into fractional-blending systems called "soleras." A "solera" consists of a stock of wine in cask, split into units of equal volume but different maturation. The oldest stage is called the "solera"; each of the younger stages that feed it is a "criadera," or nursery. There are up to seven "criaderas" in a sherry "solera," and up to 14 in a "manzanilla solera." Up to one-third (the legal maximum) of the "solera" may be drawn off for blending and bottling, although some bodegas may restrict their very high-quality, old "soleras" to one-fifth. The amount drawn off from the mature "solera" is replaced by an equal volume from the first "criadera," which is topped off by the second "criadera," and so on. When the last "criadera" is emptied of its one-third, it is refreshed by an identical quantity of "añada," or new wine. This comprises like-classified sherries from the current year's production, aged up to 36 months, depending on the style and exactly when they are finally classified.

|

|

|

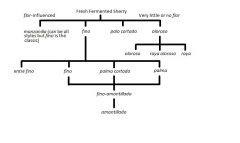

What is the evolution of sherry styles?

|

The Evolution of Sherry Styles

|