![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

45 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

Jewish Catacomb, Villa Torlonia, Rome, Late Antiquity, 3rd century CE

|

The conspicuous

representation on the Arch of Titus of the menorah looted from the Second Temple in Jerusalem kept the memory of these treasures alive in Rome. |

|

Good Shepherd, Orants, and the Story of Jonah, Catacomb of SS. Peter and Marcellinus, Rome, Late Antiquity, Late 3rd-Early 4th century

|

Derived from many biblical sources, including the 23rd Psalm, this kind of image is the most popular in the Christian art of this period. The "Good Shepherd" as an image of Jesus persisted in Christian art until about 500 AD.

|

|

The Parting of the Red Sea, Torah Niche, House Synagogue, Dura Europos, Late Antiquity, 244-45 CE.

|

In paintings on the walls, the story of

Moses unfolds in a continuous narrative around the room, employing the Roman tradition of epic historical representation. The frontal poses, strong outlines, and flat colors are pictorial devices associated with Near Eastern art. |

|

St. Michael the Archangel, Ivory Panel, Constantinople, Byzantine, 6th Century CE

|

Standing beneath an ornate arch, at the top of a flight of steps, the archangel holds and orb and a staff. The Greek inscription, which would have continued on the other leaf read: Receive the suppliant before you, despite his sinfulness.

This is the largest surviving Byzantine ivory panel and probably represents an imperial commission originating from Constantinople. It has been suggested that the angel was presenting the orb to an emperor, perhaps Justinian I (527-565 AD), who was depicted on the other lost leaf. |

|

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Church of Hagia Sophia, (Interior), Byzantine, 532-537.

|

it embodies both imperial power and Christian glory.

Anthemius was a specialist in geometry and optics, and Isidorus was a specialist in physics who had studied vaulted construction. Their crowning achievement was the dome of Hagia Sophia, which provided a golden, light-filled canopy high above a processional space. Procopius of Caesarea, who chronicled Justinian’s reign, claimed poetically that the dome seemed to hang suspended on a “golden chain from heaven.” It was rumored that Hagia Sophia was constructed by angels; in fact, mortal builders achieved the feat in only five years (532–537). |

|

Justinian as defender of the faith, (Barberini Ivory), Byzantine, mid-sixth century CE

|

The emperor is accompanied in the main panel by a conquered barbarian in trousers at left, a crouching allegorical figure, probably representing territory conquered or reconquered, who holds his foot in thanks or submission, and an angel or victory, crowning the emperor with the traditional palm of victory (which is now lost). Although the barbarian is partly hidden by the emperor's huge spear, this does not pierce him, and he seems more astonished and over-awed than combative. Above, Christ, with a fashionable curled hair-style, is flanked by two more angels in the style of pagan victory figures; he reigns above, while the emperor represents him below on earth. In the bottom panel barbarians from West (left, in trousers) and East (right, with ivory tusks, a tiger and a small elephant) bring tribute, which includes wild animals. The figure in the left panel, apparently not a saint but representing a soldier, carries a statuette of Victory; his counterpart on the right is lost.

|

|

Emperor Justinian and his Attendants, San Vitale, Ravenna, Byzantine, c.546-548.

|

The rulers present

these as precious offerings to Christ—emulating most immediately Bishop Ecclesius who offers a model of the church to Christ in the apse, as well as the Magi, wise men from the East, who brought valuable gifts to the infant Jesus, embroidered at the bottom of Theodora’s purple cloak. In fact, the chalice and paten offered by the royal couple will be used by this church to offer Eucharistic bread and wine to the local Christian community during the liturgy. At the core of this central ceremony of Christian worship is the identification of the sacrificial body and blood of Christ with the substances of bread and wine, which Jesus had instructed his followers to eat and drink in remembrance of him, and which became emblematic of his offering of himself on the cross for their redemption. In this way the entire program of mosaic decoration revolves around the theme of offering, extended into the theme of the Eucharist itself. |

|

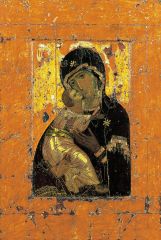

Vladimir Virgin, Constantinople, Byzantine, 12th Century

|

“The Vladimir Madonna” – is one of the most venerated Orthodox icons and a typical example of Eleusa Byzantine iconography. The Theotokos (Greek word for Virgin Mary, literally meaning “Birth-Giver of God”) is regarded as the holy protectress of Russia.

|

|

Virgin and Child with Saints and Angels, St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai, Byzantine, second half of the 6th century.

|

Perhaps the earliest iconic image of the subject to survive. The Madonna enthroned is a type of image that dates from the Byzantine period and was used widely in Medieval and Renaissance times. These representations of the Madonna and Child often take the form of large altarpieces. They also occur as frescoes and apsidal mosaics.

|

|

The Crucifixion and Iconoclasts whitewashing an icon of Christ, Khludov Psalter, Byzantine, 850-75.

|

This page and its illustration of Psalm 21, made soon after the end

of the iconoclastic controversy in 843, records the iconophiles’ harsh judgment of the iconoclasts. Painted in the margin at the right, a scene of the Crucifixion shows a soldier tormenting Christ with a vinegar-soaked sponge. In a striking visual parallel, two named iconoclasts—identified by inscription—in the adjacent picture along the bottom margin employ a whitewash-soaked sponge to obliterate an icon portrait of Christ, thus linking their actions with those who had crucified him. |

|

Andrey Rublyov, The Old Testament Trinity (Three Angels Visiting Abraham), Byzantine, 1410-1425.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Hinged Clasp, Sutton Hoo, England, Anglo-Saxon, 7th century CE.

|

Metalworking is one of the glories of Anglo-Saxon art. References

to splendid jewelry and military equipment decorated with gold and silver fill Anglo-Saxon literature, such as the epic poem Beowulf. An early seventh-century burial mound, excavated in the English region of East Anglia at a site called Sutton Hoo (hoo means “hill”), concealed a hoard of such treasures, representing the broad cultural heritage that characterized the British Isles at this time— Celtic, Scandinavian, and Classical Roman, as well as Anglo-Saxon. There was even a Byzantine silver bowl. The grave’s still unidentified occupant was buried in a 90-foot-long ship. The vessel held weapons, armor, and other equipment for the afterlife, and such luxury items as an exquisite clasp of pure gold that once secured over his shoulder the leather body armor of its wealthy and powerful owner |

|

Gold Belt Buckle, Sutton Hoo, Mound 1, Anglo-Saxon, 7th century CE.

|

take a look at the intricate craftwork on this gold belt buckle

|

|

Jewelry of Queen Arnegunde, excavated from her tomb at St. Denis, Merovingian, Paris, 580-590 CE.

|

intricate craftwork

|

|

Ship, Oseberg Ship Burial, Oseberg, Norway, Norse, 815-820 CE.

|

Oseberg Ship

|

|

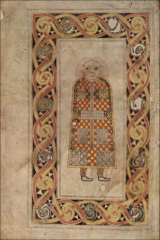

St. Matthew from the Book of Durrow, Hiberno-Saxon, 7th Century CE.

|

St. Matthew from the Book of Durrow

|

|

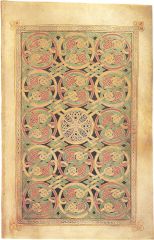

Carpet Page, Book of Durrow, Hiberno-Saxon, 7th Century CE.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

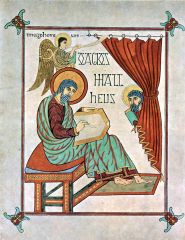

The Evangelist Matthew, Lindisfarne Gospels, Hiberno-Saxon, 710-725 CE.

|

The Lindisfarne Gospels is a Christian manuscript, containing the gospels of Matthew, Luke, Mark, and John and the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The manuscript was used for ceremonial purposes to promote and celebrate the Christian religion and the word of God (BBC Tyne 2012). Because the body of Cuthbert was buried in Lindisfarne, Lindisfarne became an important pilgrimage destination in the 7th and 8th centuries and the Lindisfarne Gospels would have contributed to the cult of Saint Cuthbert (BBC Tyne 2012).

|

|

Chi-Rho Page, Book of Kells, Hiberno-Saxon, 9th Century.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Carvings, Stave Church, Urnes, Norway, Norse, 12th Century CE.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Equestrian portrait of Charles the Bald (grandson of Charlemagne), Carolingian, Ninth century.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Interior of the Palace Chapel of Charlemagne. Aachen, Carolingian, 792-805.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

St. Matthew, Coronation Gospels, Carolingian, Early 9th Century (after 800).

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

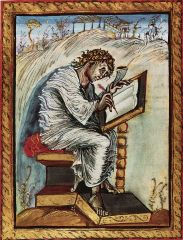

Saint Matthew. Folio 18. Ebbo Gospels, from Hautevillers, Carolingian, c.816-835.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

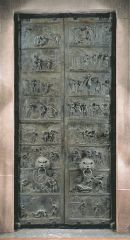

Doors, commissioned by Bishop Bernward for Saint Michael’s, Ottonian, 1015.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Exterior, Saint-Martin-du-Canigou, French Pyrenees, Romanesque, 1001-1026.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Reconstruction Drawing of the Third Abbey Church at Cluny, Looking East, Romanesque, 1088-1130.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

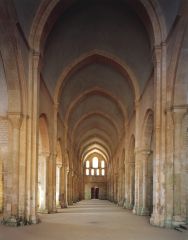

Nave, Abbey Church of Notre-Dame, Fontenay, Romanesque, 1139-1147.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Christ in Majesty, South Portal, Priory Church Moissac, Romanesque, 1115.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Hildegard and Volmar, from Liber Scivias of Hildegard of Bingen, Romanesque, 1150-1175.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Reliquary statue of Sainte Foy (St. Faith), Conques, France, Romanesque, 9th-10th centuries.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

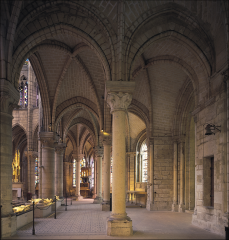

Transept, Cathedral, Santiago de Compostela, Romanesque, 1078-1122.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Giselbertus (?), Last Judgment Tympanum, Autun Cathedral, Romanesque, 1120-1130, or 1130-1145.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Tympanum, Ste. Madeleine, Vezelay, France, Romanesque, 1120-1132.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

The Bayeux Embroidery, Bayeux, France, Romanesque, 1070-1080.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Ambulatory and Radiating Chapels, St. Denis, Paris, France, Early Gothic, 1140-1144.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

West Façade, Chartres Cathedral, Early Gothic, 1134-1260.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Jambs, Royal Portal West Façade, Chartres Cathedral, Early Gothic, 1145-1155.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Rose Window and Lancets, Chartres Cathedral, High Gothic, 1230-1235.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Annunciation and Visitation, Jambs, West Portal, Reims Cathedral, High Gothic, 1230-1250.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Upper Chapel Ste. Chapelle, Paris, High Gothic, 1239-1248.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Virgin and Child, originally from St. Denis, Late Gothic, c. 1324-1339.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

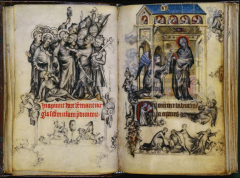

Jean Pucelle, Betrayal of Judas and the Annunciation, the Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Late Gothic, 1325-1328.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

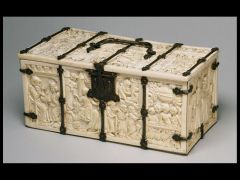

Small Ivory Chest with Scenes of Courtly Romances, Late Gothic, 1330-1350.

|

Cultural Significance.

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Virgin and Child Enthroned, Late Gothic, 1305-1310.

|

Cultural Significance.

|