![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

19 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

Praxis (origin)

|

the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted or practiced

background: In Ancient Greek the word praxis (πρᾱξις) referred to activity engaged in by free men. Aristotle held that there were three basic activities of man: theoria, poiesis and praxis. There corresponded to these kinds of activity three types of knowledge: theoretical, to which the end goal was truth; poietical, to which the end goal was production; and practical, to which the end goal was action. Aristotle further divided practical knowledge into ethics, economics and politics. He also distinguished between eupraxia (good praxis) and dyspraxia (bad praxis, misfortune) - Marx felt that philosophy's validity was in how it informed action. |

|

|

Allostasis

|

the process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological or behavioral change

|

|

|

Charge

|

Q = V*C

Charge?? - Q - is the (forces from elements in the buckets/on the plates) V is the force difference of different heights Capacitance - C is - area amt, loss on sides |

|

|

Jacques Derrida

|

(July 15, 1930 – October 8, 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher, known as the founder of deconstruction. His voluminous work has had a profound impact upon literary theory and continental philosophy. His best known work is Of Grammatology.

Derrida's method consisted in demonstrating all the forms and varieties of this originary complexity, and their multiple consequences in many fields. His way of achieving this was by conducting thorough, careful, sensitive, and yet transformational readings of philosophical and literary texts, with an ear to what in those texts runs counter to their apparent systematicity (structural unity) or intended sense (authorial genesis). By demonstrating the aporias and ellipses of thought, Derrida hoped to show the infinitely subtle ways that this originary complexity, which by definition cannot ever be completely known, works its structuring and destructuring effects.[9] |

|

|

Jürgen Habermas

|

born June 18, 1929 is a German philosopher and sociologist in the tradition of critical theory and American pragmatism. He is perhaps best known for his work on the concept of the public sphere, the topic (and title) of his first book. His work focused on the foundations of social theory and epistemology, the analysis of advanced capitalistic societies and democracy, the rule of law in a critical social-evolutionary context, and contemporary politics -- particularly German politics.

|

|

|

H-Bridge

|

1 0 0 1 Motor moves right

0 1 1 0 Motor moves left 0 0 0 0 Motor free runs 0 1 0 1 Motor brakes |

|

|

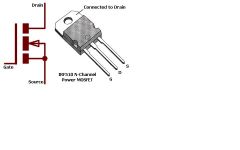

MOSFET

|

|

|

|

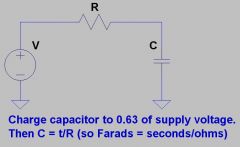

Measure Capacitance

|

|

|

|

BJT

|

bipolar junction transistor

Unlike the FET, the BJT is a low–input-impedance device Also, as the base–emitter voltage (Vbe) is increased the base–emitter current and hence the collector–emitter current (Ice) increase exponentially according to the Shockley diode model and the Ebers-Moll model. Because of this exponential relationship, the BJT has a higher transconductance than the FET. *** Bipolar transistors can be made to conduct by exposure to light, since absorption of photons in the base region generates a photocurrent that acts as a base current; the collector current is approximately beta times the photocurrent. Devices designed for this purpose have a transparent window in the package and are called phototransistors. |

|

|

Transconductance

|

Transconductance, also known as mutual conductance, is a property of certain electronic components. Conductance is the reciprocal of resistance and transconductance is the ratio of the current at the output port and the voltage at the input ports and is written as gm:

|

|

|

Horowitz

|

Horowitz, Paul & Hill, Winfield (1989). The Art of Electronics

|

|

|

Transistor

|

1. As switch in saturated region

2. As amplifier in active region Current flows with arrow in (BJT symbol - bipolar junction transistor) |

|

|

JFET

|

junction gate field-effect transistor (JFET or JUGFET) is the simplest type of field effect transistor.

|

|

|

MOSFET

|

metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET, MOS-FET, or MOS FET) is a device used to amplify or switch electronic signals. It is by far the most common field-effect transistor in both digital and analog circuits. The MOSFET is composed of a channel of n-type or p-type semiconductor material (see article on semiconductor devices), and is accordingly called an NMOSFET or a PMOSFET (also commonly nMOSFET, pMOSFET).

|

|

|

CMOS

|

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) is a major class of integrated circuits.

Two important characteristics of CMOS devices are high noise immunity and low static power consumption. Significant power is only drawn when the transistors in the CMOS device are switching between on and off states. Consequently, CMOS devices do not produce as much waste heat as other forms of logic, for example transistor-transistor logic (TTL) or NMOS logic, |

|

|

Aporia

|

Aporia (Ancient Greek: ἀπορία: impasse; lack of resources; puzzlement; embarrassment ) denotes, in philosophy, a philosophical puzzle or state of puzzlement, and, in rhetoric, a rhetorically useful expression of doubt.

Philosophy In philosophy, an aporia is a philosophical puzzle or a seemingly insoluble impasse in an inquiry, often arising as a result of equally plausible yet inconsistent premises. It can also denote the state of being perplexed, or at a loss, at such a puzzle or impasse. The notion of an aporia is principally found in Greek philosophy, but it also plays a role in Derrida's philosophy. Plato's early dialogues are often called his 'aporetic' dialogues because they typically end in aporia. In such a dialogue, Socrates questions his interlocutor about the nature or definition of a concept, for example virtue or courage. Socrates then, through elenctic testing, shows his interlocutor that his answer is unsatisfactory. After a number of such failed attempts, the intelocutor admits he is in aporia about the examined concept, concluding that he does not know what it is. In Plato's Meno (84a-c), Socrates describes the purgative effect of reducing someone to aporia: it shows someone who merely thought he knew something that he does not in fact know it and instills in him a desire to investigate it. In Aristotle's Metaphysics aporia plays a role in his method of inquiry. In contrast to a rationalist inquiry that begins from a priori principles, or an empiricist inquiry that begins from a tabula rasa, Aristotle begins his inquiry in the Metaphysics by surveying the various aporiai that exist, drawing in particular on what puzzled his predecessors. Aristotle claims that 'with a view to the science we are seeking (i.e. metaphysics), it is necessary that we should first review the things about which we need, from the outset, to be puzzled' (995a24). Book Beta of the Metaphysics is a list of the aporiai that preoccupy the rest of the work. [edit] Rhetoric Aporia is also a rhetorical device whereby the speaker expresses a doubt - often feigned - about his position or asks the audience rhetorically how he or she should proceed. It is also called dubitatio. For example (Demosthenes On The Crown, 129): |

|

|

Alterity

|

Alterity is a philosophical term meaning "otherness", strictly being in the sense of the other of two (Latin alter).

*** It is generally now taken as the philosophical principle of exchanging one's own perspective for that of the "other." The concept was established by Emmanuel Lévinas in a series of essays, collected under the title Alterity and Transcendence. The term is also deployed outside of philosophy, notably in anthropology by scholars such as Nicholas Dirks, Johannes Fabian, Michael Taussig and Pauline Turner Strong to refer to the construction of cultural others. The term has gained further use in seemingly somewhat remote disciplines, e. g. historical musicology where it is effectively employed by John Michael Cooper in a study of Goethe and Mendelssohn. |

|

|

Extimity

|

extimity, or in its French original, extimite´. Extimity is a term from the

Lacanian tradition of psychoanalysis, which I have found to be quite useful in understanding the dynamics of Sufi tradition in Muslim societies. It is the result of mixing two terms: ‘‘exteriority’’ and ‘‘intimacy’’. And it is employed to refer to the existence of the ‘‘Other’’ in the very heart of the ‘‘Self ’’, or the existence, at the very center of a system, of that which is supposed to be the most foreign to that system. By ‘‘that system’’ one may intend the individual self, the collective symbolic network, or the meaning and power systems that hold together a religion or a society (for more detailed discussion of systems and the notion of extimity see for example Miller, 1994; or Shepherdson, 1996). *** Lacan dot com - Jacques-Alain Miller: "The term extimacy (extimité), coined by Lacan from the term “intimacy” (intimité), occurs two or three times in the Seminar, - translate? |

|

|

etiology

|

The study of the causes. For example, of a disorder. (mostly medicine)

1: cause, origin ; specifically : the cause of a disease or abnormal condition 2: a branch of knowledge concerned with causes ; specifically : a branch of medical science concerned with the causes and origins of diseases |