![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

82 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

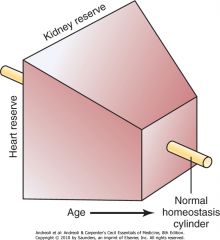

homeostenosis

|

Across cell types and organ systems, certain consistent age-related alterations in function exist.

Variability in tissue and organ function decreases, as evidenced by less fluctuation in heart rate or hormone secretion. Organ systems also exhibit predictable declines in function over time. These changes are most evident at times of stress, and ultimately these systems are slower to react and recover. The overall result is an impaired ability to deal with any demands beyond a narrow range outside the normal. This progressive narrowing in reserve, often termed "homeostenosis," can be depicted as a steady tapering in the reserve available in multiple organ systems as time progresses |

|

|

Scientific research provides a number of plausible theories of aging, which can be grouped into two major categories.

|

Error or damage theories

Program theories |

|

|

Error or damage theory of aging

|

propose that aging occurs because of persistent threats from damaging agents and an ever-declining ability to respond to or repair this damage.

|

|

|

Program theory of aging

|

postulate that genetic and developmental factors most significantly determine the biologic life course and the maximal age of the organism. In actuality, biologic aging may reflect a complex combination of many types of events.

|

|

|

The free radical theory of aging

|

proposes that oxidative metabolism results in an excess of highly reactive byproducts, called oxygen free radicals, which damage proteins, DNA, and lipids.

Molecular injury leads to cell dysfunction and ultimately to tissue and organ disrepair. Proponents of this hypothesis may argue that organisms with higher metabolic rates live shorter lives (presumably because of a more rapid accumulation of byproducts). Although the latter portion of the theory has been called into question, many still contend that limiting the production of oxidants can improve health and possibly extend life |

|

|

the only intervention that has been shown to reproducibly extend the maximal life span

|

Caloric restriction, or the purposeful reduction of food intake

In rats, life span increases an average of 20 months with a 40% reduction in calories. Rhesus monkeys enrolled in a trial of caloric restriction appear to have a lower disease burden and mortality than controls after 15 years. The mechanism is not well understood but may be metabolically mediated |

|

|

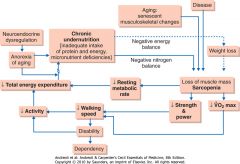

frailty

|

the increased vulnerability of humans to illness and functional decline in late life-a state

|

|

|

cycle of frailty

|

). Five key elements form the core of this cycle, including the following:

Weight loss Weakness Poor endurance Slowness Inactivity Frailty is defined as the presence of three or more of these conditions. |

|

|

frailty independently predicts

|

falls, declines in mobility, loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), hospitalization, and death.

|

|

|

define: function

|

a person's ability to perform tasks and fulfill social roles across a broad range of complexity

self-care capacity |

|

|

self-care capacity is most often divided into

|

basic, instrumental, and advanced ADLs

|

|

|

Basic ADLs

|

those actions that maintain personal health and hygiene, including transferring, bathing, toileting, dressing, and eating

|

|

|

Instrumental ADLs (IADLs)

|

include activities necessary for living independently, specifically driving, cooking, shopping, managing medications and finances, using the telephone (or other communication device), and doing housework.

|

|

|

Advanced ADLs

|

include social or occupational functions associated with activities such as hobbies, employment, or caregiving.

|

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Myocardial Infarction

|

Altered mental status

Fatigue Fever Functional decline |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Infection

|

Altered mental status

Functional decline Hypothermia |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Hyperthyroidism

|

Altered mental status

Anorexia Atrial fibrillation Chest pain Constipation Fatigue Weight gain |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Depression

|

Cognitive impairment

Failure to thrive Functional decline |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Electrolyte Disturbance

|

Altered mental status

Falls Fatigue Personality changes |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Malignancy

|

Altered mental status

Fever Pathologic fracture |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Pulmonary Embolism

|

Altered mental status

Fatigue Fever Syncope |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Vitamin Deficiency

|

Altered mental status

Ataxia Dementia Fatigue |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Fecal Impaction

|

Altered mental status

Chest pain Diarrhea Urinary incontinence |

|

|

Atypical Disease Presentations in Older Adults: Aortic Stenosis

|

Altered mental status

Fatigue |

|

|

Changes in pharmacokinetics in older adults

|

include changes in body composition, with increased fat stores and decreased body water.

|

|

|

effect of fat soluble medications in older adults

|

Fat-soluble medications, such as benzodiazepines, have a prolonged duration of effect because of this phenomenon

|

|

|

Pharmacodynamic changes in older adults

|

include decreased sensitivity to certain commonly prescribed drugs, such as β blockers, and increased sensitivity to other agents, such as narcotics and warfarin.

|

|

|

What are some evidence-based recommendations for older adults and medication management:

|

Maintain an up-to-date medication list, including over-the counter medications and herbal supplements.

Comprehensively review medications at least once annually (if not at every visit) and, in particular, at the time of transitions between care settings (e.g., after hospitalization). A clear indication for each medication, and documentation of response to therapy (particularly for chronic conditions), should be included. Assess for duplication and drug-drug or drug-disease interactions. Using a drug information database will help with this process. Assess adherence and affordability and inquire about the patient's system for administering medications (e.g., a pillbox). Assess for specific classes of medications commonly associated with adverse events: warfarin, analgesics (particularly narcotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), antihypertensives (particularly angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors and diuretics), insulin and hypoglycemic agents, and psychotropics. Minimize or avoid use of anticholinergic medications, which present specific risks. |

|

|

The most common forms of dementia include

|

Alzheimer disease, Lewy body dementia, and vascular dementia.

|

|

|

Dementia is most often characterized by

|

impairment in one or more cognitive domains severe enough to disrupt function or occupation.

|

|

|

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

|

present when an individual has discernible cognitive limitations without apparent functional impact.

Patients with MCI develop dementia at a rate of approximately 15% per year. |

|

|

In general, a diagnosis of dementia is associated with a higher risk

|

a higher risk of falls, functional impairment, institutionalization, and death.

|

|

|

Clinicians diagnose dementia through

|

symptom and functional history (often including the input of caregivers), cognitive assessment, and physical examination. A number of instruments, including the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), clock-drawing test (CDT), and the Mini-Cog, are validated screening tools. The time-tested MMSE offers an assessment of multiple cognitive domains but does not provide adequate measure of executive function and is prone to lack of sensitivity in individuals with high premorbid intelligence and lack of specificity in those with low levels of education. Validated assessments of executive function include the CDT, verbal fluency test, or the Trail B test. Instruments also exist for collecting data regarding patient function from a relative or caregiver.

|

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Onset

|

Delirum: Acute

Dementia: Insidious |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Course

|

Delirium- Flucuating, lucid at times

Dementia: Generally stable |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Duration

|

Delirium: hours to weeks

Dementia: Months to years |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Alertness

|

Delirium: Abnormally low or high

Dementia: usually normal |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Perception

|

Delirium: Illusions and hallucinations common

Dementia: Usually normal |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Memory

|

Delirium: immediate and recent impaired

Dementia: recent and remote impaired |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Thought

|

Delirium: Disorganized

Dementia: Impoverished |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Speech

|

Delirium: Incoherent, slow, or rapid

Dementia: Word-finding difficulty |

|

|

Features of Delirium versus Dementia: Physical illness or medication causative

|

Delirium: frequently

Dementia: usually absent |

|

|

Delirium is characterized by

|

by its acuity and alteration in global cognitive function

|

|

|

What is an example of a validated tool to diagnose delirium?

|

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Per the CAM, delirium is likely present if the patient has both an acute onset of confusion with fluctuating course and inattention and either disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness |

|

|

What are key risk factors of delirium?

|

older age, cognitive impairment, comorbid illness, and functional decline

|

|

|

What are precipitating factors for delirium?

|

to acute illness include hypoxia, electrolyte abnormalities, dehydration, and malnutrition as well as medications and alcohol withdrawal

|

|

|

Delirium: treatment

|

Although treatment of delirium is difficult and revolves around the underlying medical issues, controlled trials have demonstrated that a multi-modal intervention may be effective in preventing delirium in high-risk patients.

The evidence demonstrates that the use of restraints in combative or confused older adults leads to increased morbidity and mortality. Nonpharmacologic management strategies include reorientation and preservation of sleep patterns, family or caregiver presence at the bedside, and early mobilization. The use of pharmacologic agents, specifically neuroleptics or sedative hypnotics such as benzodiazepines, should be reserved for cases in which nonpharmacologic strategies do not help and the patient presents a risk of harm to himself or herself or others. |

|

|

Among older adults, depression can manifest

|

manifest atypically with cognitive, functional, or sleep problems as well as complaints of fatigue or low energy.

|

|

|

Risk factors for falls include

|

a history of falls, fear of falling, decreased vision, cognitive impairment, medications (particularly anticholinergic, psychotropic, and cardiovascular medications), diseases causing problems with strength and coordination, and environmental factors.

|

|

|

For patients who report falling, the assessment should include

|

review of circumstances of the fall(s), measure of orthostatic vital signs, visual acuity testing, cognitive evaluation, and gait and balance assessment.

|

|

|

"timed get up and go"

|

A brief physical examination maneuver called the "timed get up and go" has the patient arise from a sitting position, walk 10 feet, turn, and return to the chair to sit.

. A time of more than 16 seconds to complete the process, or observation of postural instability or gait impairment, suggests an increased risk of falling |

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling: Circumstances of previous falls

|

Change in environment and activity to reduce the likelihood of recurrent falls

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling: Medication use

High-risk medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, other sleep medications, neuroleptics, antidepressants, anticonvulsives, or class IA antiarrhythmics)*†‡ Four or more medications‡ |

Review and reduction of medications

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling:Vision*

Acuity <20/60 Decreased depth perception Decreased contrast sensitivity Cataracts |

Ample lighting without glare; avoidance of multifocal glasses while walking; referral to an ophthalmologist

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling:Postural blood pressure (after ≥5 min in a supine position, immediately after standing, and 2 min after standing)‡

≥20 mm Hg (or ≥20%) drop in systolic pressure, with or without symptoms, either immediately or after 2 min of standing |

Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; review and reduction of medications; modification of salt restriction; adequate hydration; compensatory strategies (e.g., elevating head of bed, rising slowly, or performing dorsiflexion exercises); pressure stockings; pharmacologic therapy if the above strategies fail

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling: Balance and gait†‡

Patient's report or observation of unsteadiness Impairment on brief assessment (e.g., the "get up and go" test or performance-oriented assessment of mobility) |

Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; reduction of medications that impair balance; environmental interventions; referral to physical therapist for assistive devices and for gait, balance, and strength training

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling:

Assessment and Risk Factor Management Circumstances of previous falls* Change in environment and activity to reduce the likelihood of recurrent falls Medication use High-risk medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, other sleep medications, neuroleptics, antidepressants, anticonvulsives, or class IA antiarrhythmics)*†‡ Four or more medications‡ Review and reduction of medications Vision* Acuity <20/60 Decreased depth perception Decreased contrast sensitivity Cataracts Ample lighting without glare; avoidance of multifocal glasses while walking; referral to an ophthalmologist Postural blood pressure (after ≥5 min in a supine position, immediately after standing, and 2 min after standing)‡ ≥20 mm Hg (or ≥20%) drop in systolic pressure, with or without symptoms, either immediately or after 2 min of standing Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; review and reduction of medications; modification of salt restriction; adequate hydration; compensatory strategies (e.g., elevating head of bed, rising slowly, or performing dorsiflexion exercises); pressure stockings; pharmacologic therapy if the above strategies fail Balance and gait†‡ Patient's report or observation of unsteadiness Impairment on brief assessment (e.g., the "get up and go" test or performance-oriented assessment of mobility) Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; reduction of medications that impair balance; environmental interventions; referral to physical therapist for assistive devices and for gait, balance, and strength training Targeted neurologic examinations Impaired proprioception* Impaired cognition* Decreased muscle strength†‡ |

Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; increase in proprioceptive input (with an assistive device or appropriate footwear that encases the foot and has a low heel and thin sole); reduction of medications that impair cognition; awareness on the part of caregivers of cognitive deficits; reduction of environmental risk factors; referral to physical therapist for gait, balance, and strength training

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling:

Assessment and Risk Factor Management Circumstances of previous falls* Change in environment and activity to reduce the likelihood of recurrent falls Medication use High-risk medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, other sleep medications, neuroleptics, antidepressants, anticonvulsives, or class IA antiarrhythmics)*†‡ Four or more medications‡ Review and reduction of medications Vision* Acuity <20/60 Decreased depth perception Decreased contrast sensitivity Cataracts Ample lighting without glare; avoidance of multifocal glasses while walking; referral to an ophthalmologist Postural blood pressure (after ≥5 min in a supine position, immediately after standing, and 2 min after standing)‡ ≥20 mm Hg (or ≥20%) drop in systolic pressure, with or without symptoms, either immediately or after 2 min of standing Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; review and reduction of medications; modification of salt restriction; adequate hydration; compensatory strategies (e.g., elevating head of bed, rising slowly, or performing dorsiflexion exercises); pressure stockings; pharmacologic therapy if the above strategies fail Balance and gait†‡ Patient's report or observation of unsteadiness Impairment on brief assessment (e.g., the "get up and go" test or performance-oriented assessment of mobility) Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; reduction of medications that impair balance; environmental interventions; referral to physical therapist for assistive devices and for gait, balance, and strength training Targeted neurologic examinations Impaired proprioception* Impaired cognition* Decreased muscle strength†‡ Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; increase in proprioceptive input (with an assistive device or appropriate footwear that encases the foot and has a low heel and thin sole); reduction of medications that impair cognition; awareness on the part of caregivers of cognitive deficits; reduction of environmental risk factors; referral to physical therapist for gait, balance, and strength training Targeted musculoskeletal examinations of legs (joints and range of motion) and examination of feet* |

Diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause, if possible; referral to physical therapist for strength, range-of-motion, and gait and balance training, and for assistive devices; use of appropriate footwear; referral to podiatrist

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling: Targeted cardiovascular examination†

Syncope Arrhythmia (if there is known cardiac disease, abnormal electrocardiogram, and syncope |

Referral to cardiologist; carotid-sinus massage (in case of syncope)

|

|

|

Recommended Components of Clinical Assessment and Management for Older Persons Living in the Community Who Are at Risk for Falling: Home-hazard evaluations after hospital discharge†‡

|

Removal of loose rugs and use of nightlights, nonslip bathmats, and stair rails; other interventions as necessary

|

|

|

Given the implications of vision loss for function and safety, a general ophthalmologic examination every _______ years is recommended for all older adults

|

1-2 years

|

|

|

Ideally, all older adults should undergo ________ hearing screen by questionnaire and handheld audiometry

|

annual

|

|

|

The impact of UI on health ranges from

|

from increased risk of skin irritation, pressure wounds, and falls to social isolation, functional decline, and depression.

|

|

|

It is important to first determine if the incontinence is

|

acute or chronic in nature

|

|

|

Acute causes of incontinence are often attributable to

|

specific medical problems, including infection, metabolic disturbance, or medication effects.

The pneumonic DIAPERS recalls the various potential acute causes of UI (D, delirium; I, infection; A, atrophic vaginitis; P, pharmaceuticals; E, excess urine output from congestive heart failure (CHF) or hyperglycemia; R, restricted mobility; and S, stool impaction). |

|

|

What is the most common cause of urinary incontinence

|

urge incontinence from detrusor overactivity

|

|

|

urge incontinence

|

from detrusor over activity

Patients with this problem will complain of urinary frequency, nocturia, and a sudden onset of urge to void. |

|

|

Stress incontinence

|

occurs with incompetence of pelvic musculature or urethral sphincter and is characterized by small amounts of leakage with laughing, sneezing, coughing, or even standing.

|

|

|

Overflow incontinence

|

results from urinary retention, often related to prostatic hyperplasia in men or bladder atony in patients with diabetes or spinal cord injury. Patients often have constant dribbling or leakage without a true sense of needing to void.

|

|

|

functional incontinence

|

results from comorbid conditions that limit a patient's ability to act on or interpret the need to void, mobility problems such as arthritis, and weakness or cognitive problems.

|

|

|

stress incontinence: definition

|

Leakage associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure (coughing, sneezing)

|

|

|

stress incontinence: cause

|

Hypermobility of the bladder base, frequently caused by lax perineal muscles

|

|

|

stress incontinence: treatment

|

Pelvic muscle exercise, timed voiding, α-adrenergic drugs, estrogens, surgery

|

|

|

urge incontinence: definition

|

Leakage associated with a precipitous urge to void

|

|

|

urge incontinence: cause

|

Detrusor hyperactivity (outflow obstruction, bladder tumor, detrusor instability), idiopathic (poor bladder), compliance (radiation cystitis), hypersensitive bladder

|

|

|

urge incontinence: treatment

|

Bladder training, pelvic muscle exercise, bladder-relaxant drugs (anticholinergics, oxybutynin, tolterodine, imipramine)

|

|

|

Overflow incontinence: definition

|

Leakage from a mechanically distended bladder

|

|

|

overflow incontinence: causes

|

Outflow obstruction, enlarged prostate, stricture, prolapsed cystocele, acontractile bladder (idiopathic, neurologic [spinal cord injury, stroke, diabetes])

|

|

|

overflow incontinence: treatment

|

Surgical correction of obstruction, intermittent catheter drainage

|

|

|

functional incontinence: definition

|

Inability or unwillingness to void

|

|

|

functional incontinence: causes

|

Cognitive impairment, physical impairment, environmental barriers (physical restraints, inaccessible toilets), psychological problems (depression, anger, hostility)

|

|

|

functional incontinence: treatment

|

Prompted voiding, garment and padding, external collection devices

|