![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

101 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

- 3rd side (hint)

|

Past questions were based on following topics |

1 Ageing 2 Organizing geriatric services 3 Clinical assessment of older people 4 Rehabilitation 5 Falls and funny turns 6 Drugs 7 Neurology 8 Stroke 9 Psychiatry 10 Cardiovascular 11 Chest medicine 12 Gastroenterology 13 Renal medicine 14 Homeostasis 15 Endocrinology 16 Haematology 17 Musculoskeletal system 18 Pressure injuries 19 Genitourinary medicine 20 Incontinence 21 Ears 22 Eyes 23 Skin 24 Infection and immunity 25 Malignancy 26 Death and dying 27 Ethics 28 Finances 29 Peri-operative medicine |

|

|

|

Ageing

|

2 |

|

|

|

2 Organizing geriatric services |

1 |

|

|

|

3 Clinical assessment of older people

|

1 |

|

|

|

4 Rehabilitation |

1 |

|

|

|

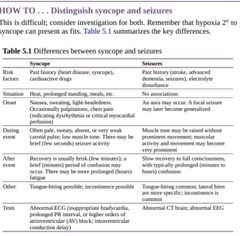

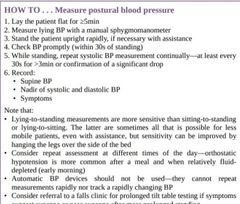

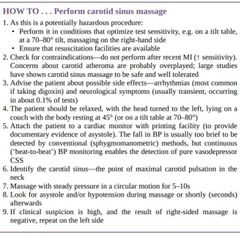

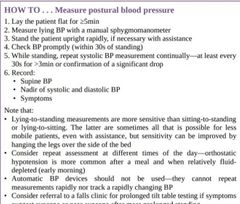

Falls and funny turns Falls and fallers▪︎Assessment following a fall▪︎Interventions to prevent falls▪︎Syncope and presyncope▪︎HOW TO Distinguish syncope and seizures▪︎Balance and disequilibrium▪︎Dizziness▪︎HOW TO Manage multifactorial dizziness—clinical example▪︎Drop attacks▪︎Orthostatic (postural) hypotension▪︎Situational hypotension▪︎HOW TO Measure postural blood pressure▪︎Carotid sinus syndrome▪︎HOW TO Perform carotid sinus massage▪︎Falls services |

1 falls causes 2 falls management -support 3 |

|

|

|

Falls and fallers► A fall is often a symptom of an underlying serious problem and is not a partof normal ageing.A fall is an event that results in a person non-intentionally coming to rest at alower level (usually the floor) with or without loss of consciousness. Falls arecommon and important, affecting one-third of older people living in their ownhomes each year. They result in fear, injury, dependency, institutionalization, and death. Many can be prevented and their consequences minimized. |

Factors influencing fall frequency ▪︎Intrinsic factors. Maintaining balance and avoiding a fall is a complex,demanding multisystem skill. It requires 1.muscle strength (power:weight ratio), 2.stable but flexible joints, 3.multiple sensory modalities (e.g. proprioception,vision, hearing), and a 4.functional peripheral and central nervous system. 5.Higher-level cognitive function permits risk assessment, giving insight into the danger that a planned activity may pose ▪︎Extrinsic factors. These include environmental factors, e.g. lighting, obstacles,the presence of grab rails, and the height of steps and furniture, as well as the softness and grip of the floor

Magnitude of ‘stressor’. All people have the susceptibility to fall, and thelikelihood of a fall depends on how close to a ‘fall threshold’ a person sits. Older people, especially with disease, sit closer to the threshold and are more easily and more often pushed over it by stressors. ▪︎ These can be internal (e.g.transient dizziness due to orthostatic hypotension) or ▪︎external (e.g. a gust ofwind or a nudge in a crowded shop); they may be minor or major (no one can avoid ‘falling’ during syncope) If insight is preserved, the older person can, to some extent, reduce risk by limiting hazardous behaviours and minimizing stressors (e.g. walking only inside, avoiding stairs or uneven surfaces, using walking aids, or asking for supervision).

▪︎Factors influencing fall severity In older people, the adverse consequences of falling are greater, due to: Multiple system impairments which lead to less effective saving mechanisms. Falls are more frightening and injury rates per fall are higher Osteoporosis and ↑ fracture rates 2° injury due to post-fall immobility, including pressure sores, burns,dehydration, and hypostatic pneumonia. Half of older people cannot get upagain after a fall Psychological adverse effects, including loss of confidence ▪︎Falls are almost always multifactorial. Think:‘Why today?’ Often because the fall is a manifestation of acute or subacuteillness, e.g. sepsis, dehydration, or drug adverse effect‘ Why this person?’ Usually because of a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that ↑ vulnerability to stressors. Banned terms The terms simple fall and mechanical fall are used commonly, but they are facile, imprecise, and unhelpful. ‘Simple’ usually refers to the approach adopted by the assessing doctor.For every fall, identify the intrinsic factors, extrinsic factors, and acute stressors that have led to it.Within each of these categories, think how their influence on the likelihood of future falls can be reduced. |

Assessment following a fall Think of fall(s) if a patient presents: ~Having ‘tripped’ With a fracture or non-fracture injury ~Having been found on the floor ~With 2° consequences of falling (e.g. hypothermia, pneumonia) Patients who present having fallen are often mislabelled as having ‘collapsed’,discouraging the necessary search for multiple causal factors. ▪︎Practise opportunistic screening—ask all older people who attend 1° or 2°care whether they have fallen recently. History Obtain a corroborative history, if possible. May often need to use very specific,detailed, and directed questions. In many cases, a careful history differentiates between falls due to: ▪︎Frailty and unsteadiness ▪︎Syncope or near-syncope ▪︎Acute neurological problems (e.g. seizures, vertebrobasilar insufficiency(VBI))

Gather information about: ▪︎Fall circumstances (e.g. timing, physical environment) ▪︎Symptoms before and after the fall ▪︎Clarification of symptoms, e.g. ‘dizzy’ may be vertigo or presyncope ▪︎Drugs, including alcohol ▪︎Previous falls, fractures, and syncope (‘faints’), even as a young adult ▪︎Previous ‘near-misses’ ▪︎Comorbidity (cardiac, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, seizures, cognitive impairment, diabetes, incontinence) ▪︎Functional performance (difficulties bathing, dressing, toileting) ▪︎Drugs associated with falls ~Falls may be caused by any drug that either is directly psychoactive or may lead to systemic hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion. ~Polypharmacy (>4 drugs,any type) is an independent risk factor. ~The most common drug causes are •Benzodiazepines and other hypnotics •Antidepressants (tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) •Antipsychotics •Opiates •Diuretics •Antihypertensives, especially ACE inhibitors and α-blockers •Antiarrhythmics •Anticonvulsants •Skeletal muscle relaxants, e.g. baclofen, tizanidine •Hypoglycaemics, especially long-acting oral drugs and insulin

Examination This can sometimes be focused if the history is highly suggestive of a particular pathology; ~perform at least a brief screening examination of each system. ~Functional. ▪︎Ask the patient to stand from a chair, walk, turn around, walkback, and sit back down (‘get up and go’ test). ▪︎Assess gait, use of walking aids, and hazard appreciation ▪︎Cardiovascular. ~ Always check lying and standing BP. ~Check pulse rate and rhythm. ~Listen for murmurs (especially of aortic stenosis) ▪︎Musculoskeletal. ~Assess foot wear (stability and grip). ~Remove footwear and examine the feet. ~ Examine the major joints for deformity, instability, or stiffness ▪︎Neurological. ~To identify stroke, peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease,vestibular disease, myelopathy, cerebellar degeneration, and cognitive impairment VisionTests

The following are considered routine: ECG FBC, B12, folate, U, C+E, glycosylated Hb (HbA1c), calcium, phosphate, TFT Vitamin D deficiency is common in older adults, and evidence suggests that replacing may reduce falls/harm from falls If a specific cause is suspected, then test for it, e.g.:24h ECG in a patient with frequent near-syncope and a resting ECG suggesting conducting system disease Echocardiogram in a patient with systolic murmur and other features suggesting aortic stenosis (e.g. slow-rising pulse, left ventricular hypertrophy(LVH) on ECG) Head-up tilt table testing (HUTT) in patients with unexplained syncope, normal resting ECG, and no structural heart disease However, all tests have false positive rates, and even a ‘true positive’ finding may have no bearing on the patient’s presentation. For example, a patient falling due to osteoarthritis and physical frailty will not benefit from an echocardiogram that reveals asymptomatic mild aortic stenosis. ► Use tests selectively, based on your judgement (following careful historyand examination) of the likely factors contributing to falls. |

|

|

Balance and disequilibrium Balancing is a complex activity, involving many systems. Input There must be awareness of the position of the body in space, which comes from:Peripheral input—information about body position comes from peripheral nerves (proprioception) and mechanoreceptors in the joints. This information is relayed via the posterior column of the spinal cord to the central nervous system (CNS) Eyes—provide visual cues as to position Ears—provide input at several levels. The otolithic organs (utricle and saccule) provide information about static head position. The semicircular canals inform about head movement. Auditory cues localize a person with reference to the environment Assimilation Information is gathered and assessed in the brainstem and cerebellum. Output Messages are then relayed to the eyes, to allow a steady gaze during head movements (the vestibulo-ocular reflex), and to the cortex and the cord to control postural (anti gravity) muscles. When all this functions well, balance is effortless. A defect(s) in any one contributing system can cause balance problems or disequilibrium: Peripheral nerves—neuropathy is more common. Specifically, it is believed that there is a significant age-related loss of proprioceptive function Eyes—age-related changes ↓ visual acuity. Disease (cataracts, glaucoma, etc.)is more common Ears—age-related changes ↓ hearing and lead to reduced vestibular function. The older vestibular system is more vulnerable to damage from drugs, trauma,infection, and ischaemia Joint receptors—degenerative joint disease (arthritis) is more common in older people CNS—age-related changes can slow processing. Disease processes(ischaemia, hypertensive damage, dementia, etc.) are more common with age Postural muscles—sarcopenia (a syndrome of reduced muscle mass with weakness) due to inactivity, disease, medication (e.g. steroids), or intrinsic ageing In the older person, one or more of these defects will occur commonly. In addition, skeletal changes may alter the centre of gravity, and cardiovascular changes may lead to arrhythmias or postural change in BP, exacerbated furtherby medications. An approach to disequilibrium ▪︎Aetiology is usually multifactorial ▪︎Consider each system separately, and optimize its function ▪︎Look at provoking factors (medication, cardiovascular conditions,environmental hazards, etc.) and minimize them ▪︎Work on prevention:Alter the environment (e.g. improve lighting) Develop safer ways to mobilize, and ↑ strength, stamina, and balance Small adjustments to multiple problems can make a big difference, e.g. when appropriate, combine cataract extraction, a walking aid, vascular 2°prevention, a second stair rail, brighter lighting, and a course of PT ► If falls persist, despite simple (but multiple) interventions, refer to a falls clinic. |

Dizziness A brain that has insufficient information to be confident of where it is in space generates a sensation of dizziness. This can be due to reduced sensory inputs or impairment of their integration. Dizziness is common, occurring in up to 30% of older people. However, the term dizziness can be used by patients and doctors to mean many different things, including: Movement (spinning) of the patient or the room—vertigo Light-headedness—syncope and presyncope Mixed—a combination of these sensations Other, e.g. malaise, general weakness, headache Distinguishing these is the first step in management, as it will indicate possible causal conditions. This relies largely on the history. Discriminatory questionsinclude: ‘Please try to describe exactly what you feel when you are dizzy’‘Does the room spin, as if you are on a roundabout?’ (vertigo) ‘Do you feel light-headed, as if you are about to faint?’ (presyncope)‘ Does it occur when you are lying down?’ (if so, presyncope is unlikely)‘ Does it come on when you move your head?’ (vertigo more likely)‘ Does it come and go?’ (chronic, constant symptoms are more likely to bemixed or psychiatric in origin) Causes The individual conditions most commonly diagnosed when a patient complains of dizziness are: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) Labyrinthitis Posterior circulation stroke Orthostatic hypotension Carotid sinus hypersensitivity VBI Cervical spondylosis Anxiety and depression In reality, much dizziness is multifactorial, with dysfunction in several systems.This means that precise diagnosis is more difficult (and often not done) and treatment is more complex. ► Making small improvements to each contributing problem can add up to abig overall improvement (perhaps making the difference between independent living or institutional care). |

Drop attacks This term refers to unexplained falls with no prodrome, no (or very brief) loss ofconsciousness, and rapid recovery. The proportion of falls due to ‘drop attack’ ↑with age. There are several causes, including: Cardiac arrhythmia Carotid sinus syndrome (CSS) Orthostatic hypotension Vasovagal syndrome VBI Weak legs (e.g. cauda equina syndrome) The first four causes listed usually lead to syncope or presyncope, with identifiable prior symptoms (e.g. dizziness, pallor); those episodes would not be termed ‘drop attacks’. However, such prior symptoms are not universal and maynot be recollected, leading to a ‘drop attack’ presentation. In most cases, following appropriate assessment, the cause(s) can be identified and effective treatment(s) begun. ► Making a diagnosis of ‘drop attack’ alone is not satisfactory; assess more completely and, where possible, determine the likely underlying cause(s) |

|

|

Interventions to prevent falls The complexity of treatment reflects the complexity of aetiology: Older people who fall more often have remediable medical causes Do not expect to make only one diagnosis or intervention—making minor changes to multiple factors is more powerful Tailor the intervention to the patient. Assess for relevant risk factors and workto modify each one ▪︎A multidisciplinary approach is key Reducing fall frequency ▪︎Drug review. Try to reduce the overall number of medications. ~For each drug,weigh the benefits of continuing with the benefits of reduction or stopping.Stop if risk is greater than benefit. ~Reduce if benefit is likely from the drug class, but the dose is excessive for that patient. ~ Taper to a stop if withdrawal effect likely, e.g. benzodiazepine Treatment of orthostatic hypotension ▪︎Strength and balance training. In the frail older person, by a PT, exercise classes, or disciplines such as t’ai chi ▪︎Walking aids. Provide an appropriate aid and teach the patient how to use it ▪︎Environmental assessment and modification (a simple checklist can help the family minimize risk; in some cases, a more detailed assessment by an OT isbeneficial) ▪︎Vision. Ensure glasses are appropriate (avoid vari- or bifocal lenses) ▪︎Reducing stressors. This involves decision-making by the patient or carers.The cognitively able patient can judge risk/benefit and usually modifies risk appropriately, e.g. limiting walking to indoors, using a walking aid properly and reliably, and asking for help if a task (e.g. getting dressed) is particularly demanding. However:Risk can never be abolished Enforced relative immobility has a cost to health Patient choice is paramount. Most will have clear views about risk and how much lifestyle should change ▪︎Institutionalization does not usually reduce risk Preventing adverse consequences of falls Despite risk reduction, falls may remain likely. In this case, consider: ▪︎Osteoporosis detection and treatment ▪︎Teaching patients how to get up. Usually by a PT ▪︎Alarms, e.g. pullcords in each room or a pendant alarm (worn around theneck/wrist). Often these alert a distant call centre, which summons more local help (home warden, relative, or ambulance) ▪︎Supervision. Continual visits to the home (by carers, neighbours, family,and/or voluntary agencies) reduce the duration of a ‘lie’ post-fall ▪︎Change of accommodation. This sometimes reduces risk but is not a panacea.A move from home to a care home may provide a more suitable physical environment, but it will be unfamiliar and staff cannot provide continuous supervision. Preventing falls in hospital Falls in hospital are common, a product of admitting acutely unwell older people with chronic comorbidity into an unfamiliar environment. Multifactorial interventions (such as FallSafe) have the best chance of reducing falls: Treat infection, dehydration, and delirium actively Stop incriminated drugs and avoid starting them Provide good-quality footwear and an accessible walking aid Provide good lighting and a bedside commode for those with urinary or faecal urgency or frequency Keep a call bell close to hand Care for the highest-risk patients in a bay under continuous staff supervision

Interventions that are rarely effective and may be harmful ▪︎Bedrails (cotsides). Injury risk is substantial limbs snag on unprotected metal bars and patients clamber over the rails, falling even greater distances onto the floor below ▪︎Restraints. These ↑ the risk of physical injury, including fractures, pressure sores, and death. Also ↑ agitation ▪︎Hip protectors are impact-absorptive pads stitched into undergarments. Evidence of efficacy is limited to care home residents and they cause more falls in community-dwelling trials. |

Syncope and presyncope ▪︎Syncope is a sudden, transient loss of consciousness due to reduced cerebral perfusion. The patient is unresponsive with a loss of postural control (i.e. slumpsor falls). ▪︎Presyncope is a feeling of light-headedness that would lead to syncope if corrective measures were not taken (usually sitting or lying down). These conditions:Are a major cause of morbidity (occurring in a quarter of institutionalized older people), recurrent in one-third. ▪︎Risk of syncope ↑ with advancing age and in the presence of cardiovascular disease ▪︎Accounts for up to 5% of hospital attendances and many serious injuries (e.g.hip fracture) ▪︎Cause considerable anxiety and can cause social isolation as sufferers limit activities in fear of further episodes. Causes These are many. Older people with ↓ physiological reserve are more susceptible to most. They can be subdivided as follows: ▪︎Peripheral factors. Hypotension may be caused by an upright posture, eating,straining, or coughing, and may be exacerbated by low circulating volume(dehydration), hypotensive drugs, or intercurrent sepsis. •Orthostatic hypotension is the most common cause of syncope •Vasovagal syncope (‘simple faint’). Common in young and old people. Vagal stimulation (pain, fright, emotion, etc.) leads to hypotension and syncope. Usually, an autonomic prodrome (pale, clammy, light-headed) is followed by nausea or abdominal pain, then syncope. Benign, with no implications for driving. Diagnose with caution in older people with vascular disease where other causes are more common •Carotid sinus hypersensitivity syndrome •Pump problem. MI or ischaemia, arrhythmia (tachy- or bradycardia, e.g.ventricular tachycardia (VT), supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), fast atrial fibrillation (AF), complete heart block, etc.) •Outflow obstruction, e.g. aortic stenosis. PE is also a type of out flow obstruction. The main differential is seizure disorder where loss of consciousness is due to altered electrical activity in the brain . Stroke and TIA very rarely cause syncope, as they cause a focal, not global,deficit. Brainstem ischaemia is the rare exception.► A significant proportion of patients referred to specialist clinics for assessment of ‘syncope’ or ‘blackout’ are found not to have lost consciousness,but to have had a fall 2° to gait or balance abnormalities. |

History The history often yields the diagnosis, but accuracy can be difficult to achieve the patient often remembers little. Witness accounts are valuable and should be sought. Ensure that the following points are covered: ︎Situation—was the patient ▪︎standing (orthostatic hypotension), ▪︎exercising(ischaemia or arrhythmia), ▪︎sitting, or lying down (likely seizure), ▪︎eating(postprandial hypotension), ▪︎on the toilet (defecation or micturition syncope), ▪︎coughing (cough syncope), or ▪︎in pain or frightened (vasovagal syncope)? Prodrome—was there any warning? ▪︎Palpitations suggest arrhythmia; ▪︎sweating with palpitations suggests vasovagal syndrome; ▪︎chest pain suggests ischaemia; ▪︎light-headedness suggests any cause of hypotension. ▪︎Gustatory or olfactory aura suggests seizures. However, associations are not absolute, e.g.arrhythmias often do not cause palpitations Was there loss of consciousness?—there is much terminology (fall, blackout,‘funny turn’, collapse, etc.), and different patients mean different things by each term. ☆Syncope has occurred if there is loss of consciousness with loss of awareness due to cerebral hypoperfusion; however, many (~30%) patients will have amnesia for the loss of consciousness and simply describe a fall Description of attack—ideally from an eye witness. ☆Was the patient deathly pale and clammy (likely systemic and cerebral hypoperfusion)? ☆Were there ictal features (tongue-biting, incontinence, twitching)? ☆Prolonged loss of consciousness makes syncope unlikely. A brain deprived of oxygen from any cause is susceptible to seizure; a fit does not necessarily indicate that a seizure disorder is the 1° problem. Assess carefully before initiating anticonvulsant therapy Recovery period—ideally reported by an eyewitness. □Rapid recovery often indicates a cardiac cause. □Prolonged drowsiness and confusion often follow aseizure Examination Full general examination is required. Ensure that the pulse is examined,murmurs sought, and a postural BP obtained.

Investigation Bloods—check for anaemia, sepsis, renal disease, myocardial ischaemia ECG—for all older patients with loss of consciousness or presyncope. Look specifically at PR interval, QT interval, trifascicular block (prolonged PR,right bundle branch block (RBBB), and left anterior fascicular block),ischaemic changes, and LVH Other tests depend on clinical suspicion, e.g. tilt test if symptoms sound orthostatic, but diagnosis is proving difficult (lying and standing BPs will usually suffice; tilt testing is a very labour-intensive test and should not be requested routinely); brain scan and electroencephalogram (EEG) if seizures suspected; prolonged ambulatory ECG monitoring or an implantable looprecorder if looking for arrhythmias

Treatment ◇Treat the cause ◇Often not found or multifactorial, so treat all reversible factors ◇Review medication (e.g. diuretics, vasodilators, cholinesterase inhibitors,tricyclic antidepressants) ◇Education about prevention and measures to abort an attack if there is a prodrome. ◇Advise against swimming or bathing alone, and inform abou tdriving restrictions. (Varies from no restriction to a 6-month ban, depending on the type of syncope; see details ► Transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) may be caused by syncope orseizure. |

|

Orthostatic (postural) hypotension •Orthostatic hypotension is common. •About 20% of community-dwelling and 50% of institutionalized older people are affected. •An important, treatable cause of dizziness, syncope, near-syncope, immobility,falls, and fracture. Less frequently leads to visual disruption, lethargy, neckache, or backache •Often most marked after meals, exercise, at night, and in a warm environment,and abruptly precipitated by ↑ intrathoracic pressure (cough, defecation, or micturition) •Often episodic (coincidence of precipitants) and covert (ask direct questions;walk or stand the patient and look for it). •May occur several minutes after standing

Diagnosis Thresholds are arbitrary. ▪︎A fall in BP of ≥20mmHg systolic or 10mmHg diastolic on standing from supine is said to be significant. ▪︎Severity of symptoms often does not correlate well with objective BP change. Causes ▪︎Drugs (including vasodilators, diuretics, negative inotropes or chronotropes(e.g. β-blockers, calcium channel blockers), antidepressants, antipsychotics,opiates, levodopa, alcohol) ▪︎Chronic hypertension (↓ baroreflex sensitivity and LV compliance) ▪︎Volume depletion (dehydration, acute haemorrhage) ▪︎Sepsis (vasodilation) ▪︎Autonomic failure (pure, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, etc.) ▪︎Prolonged bed rest ▪︎Adrenal insufficiency ▪︎Raised intrathoracic pressure (bowel or bladder evacuation, cough)

Treatment ▪︎Treat the cause. Stop, reduce, or substitute drugs incrementally ▪︎Reduce consequences of falls (e.g. pendant alarms) ▪︎Modify behaviour—stand slowly and stepwise; lie down at prodrome ▪︎If still salt- or water-deplete, supplement with:Sodium (liberal salting at table or sodium chloride (NaCl) tablets) Water (oral or intravenous fluids) ▪︎Consider starting drugs if non-drug measures fail: ~Fludrocortisone (0.1–0.2mg/day) ~α-agonists, e.g. midodrine (2.5mg three times daily (tds), titrated to a maximum of 40mg/day); unlicensed in the UK; contraindicated in vascular disease ~Desmopressin 5–20 micrograms nocte, intranasal (used rarely in older patients as causes electrolyte imbalances) ▪︎In all cases, monitor electrolytes and for heart failure and supine hypertension. Caution if supine BP rises >180mmHg systolic. Dependent oedema alone is not a reason to stop treatment ▪︎The following may help: ~Full-length compression stockings ~Head-up tilt to bed (↓ nocturnal natriuresis) ~Caffeine (strong coffee with meals) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatorydrugs (NSAIDs) with extreme caution (→ fluid retention) ~Erythropoietin or octreotide |

Situational hypotension Postprandial hypotension Significant when associated with symptoms and fall in BP ≥20mmHg within 75min of meals. A modest fall is normal (and usually asymptomatic) in older people Often more severe and symptomatic in hypertensive people with orthostatic hypotension or autonomic failure Measure BP before meals and at 30min and 60min after meal. Symptoms and causes overlap with orthostatic hypotension

Treatment ▪︎Avoid hypotensive drugs and alcohol with meals ▪︎Lie down or sit after meals ▪︎Reduce osmotic load of meals (small frequent meals, low simple carbohydrates, high fibre/water content) ▪︎Caffeine, fludrocortisone, NSAIDs, and octreotide are used rarely Others Collapse at initiation or during defecation or micturition are commonly due to hypotension, and a similar management approach should be adopted Hypotension in response to cough can also occur—direct management towards reducing cough and optimizing BP. |

Carotid sinus syndrome ▪︎CSS is episodic, symptomatic bradycardia and/or hypotension due to ahypersensitive carotid baroreceptor reflex, resulting in syncope or near-syncope. ▪︎It is an important and potentially treatable cause of falls. ▪︎CSS is common in older patients and rarely occurs under 50 years. Series report a prevalence of 2% in healthy older people, and up to 35% of fallers >80 years. It is a condition that has been identified recently, and not all physicians are convinced that we fully understand the normal responses of older people to carotid sinus massage or the significance of the spectrum of abnormal results. ▪︎Normally, in response to ↑ arterial BP, baroreceptors in the carotid sinus act via the sympathetic nervous system to slow and weaken the pulse, lowering the BP. •This reflex typically blunts with age, but in CSS, it is exaggerated, probably centrally. •This hypersensitivity is associated with ↑ age, atheroma, and the use of drugs that affect the sinoatrial node (e.g. β-blockers, digoxin, and calcium channel blockers).

Typical triggers ▪︎Neck turning (looking up or around) ▪︎Tight collars ▪︎Straining (including cough, micturition, and defecation) ▪︎Prolonged standing Often, however, no trigger is identified. Subtypes ▪︎Cardioinhibitory (sinus pause of >3s) ▪︎Vasodepressor (BP fall of >50mmHg) ▪︎Mixed (both sinus pause and BP fall)

Diagnosis The diagnosis is made when all three of the following factors are present: 1》Unexplained attributable symptoms 2》A sinus pause of >3s and/or systolic BP fall of >50mmHg in response to 5s of carotid sinus massage. 3》Symptoms are reproduced by carotid sinus massage

CSS is often associated with other disorders (vasovagal syndrome and orthostatic hypotension), probably due to shared pathogenesis (autonomicdysfunction). This makes management more challenging.

Treatment Stop aggravating drugs where possible Pure cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity responds well to AV sequential pacing, resolving symptoms in up to 80% Vasodepressor-related symptoms are harder to treat (pathogenesis is less well understood) but may respond to ↑ circulating volume with fludrocortisone ormidodrine (not licensed), as for orthostatic hypotension. |

|

|

Falls services The assessment and 2° prevention of falls are multifactorial processes requiring a systematic approach. This is frequently appropriate in 1° and 2° care settings and can be delivered effectively by any trained member of the MDT. Morecomplex cases may benefit from assessment within a specialist setting such as a geriatric or falls clinic. Referral criteria Falls are so common that health services would be swamped if all who had fallen were referred. Instead, refer those with more sinister features suggesting a likelihood of recurrent falls, injury, or an underlying remediable cause. Referralcriteria might include: Recurrent (≥2) falls Loss of consciousness, syncope, or near-syncope Injury, especially fracture or facial injury (the latter suggesting poor saving mechanisms or loss of consciousness) Polypharmacy (≥4 drugs) Sources of patients include: ED (assess most people with non-operatively managed fractures) Acute orthopaedic units (hip and other operatively managed fractures) GP or community nurse Medical wards Self-presenting. Some services advertise directly, via posters and other media Service structure The team structure, diagnostic approach, and delivery of care vary enormously.Falls clinics are often led and delivered by non-physician health professionals such as experienced nurses, OTs, and PTs. A systematic review of possible contributing factors is essential and will usually include: Cardiovascular examination (including postural BP) Neurological examination Cognitive assessment Gait assessment Frailty assessment Environmental assessment Medication review Routine bloods (including FBC, U, C+E, haematinics, vitamin D) Screening for modifiable medical factors should be a routine part of allassessments, with referral to a medical specialist (e.g. GPSI or geriatrician) if such factors are identified. |

|

|

|

|

Drugs ▪︎Pharmacology in older patients ▪︎Prescribing ‘rules’ ▪︎Taking a drug history ▪︎HOW TO . . . Improve concordance/adherence ▪︎Drug sensitivity ▪︎Adverse drug reactions ▪︎ACE inhibitors HOW TO . . . Start ACE inhibitors ▪︎Analgesia HOW TO . . . Manage pain in older patients ▪︎Steroids ▪︎Warfarin HOW TO . . . Initiate warfarin ▪︎Direct oral anticoagulants ▪︎Proton pump inhibitors ▪︎HOW TO . . . Manage drug-induced skin rashes ▪︎Herbal medicines ▪︎Breaking the rules |

1 warfarin drug interactions Action increased by 2Skin manifestations of drug reactions |

|

|

|

Pharmacology in older patients Perhaps the most common intervention performed by physicians is to write aprescription. Older patients will have more conditions requiring medication;polypharmacy is common.

In the developed world:The over 65s typically make up around 14% of the population yet consume 40% of the drug budget 66% of the over 65s and 87% of the over 75s are on regular medication 34% of the over 75s are on three or more drugs Care home patients are on an average of eight medications Good prescribing habits are essential for any medical practitioner, but especially for the geriatrician.

Administration challenges include ▪︎Packaging may make tablets hard to access—childproof bottles and tablets in blister packets can be impossible to open with arthritic hands or poor vision ▪︎Labels may be too small to read with failing vision ▪︎Tablets may be large and difficult to swallow (e.g. co-amoxiclav) or have an unpleasant taste (e.g. potassium supplements) ▪︎Liquid formulations can be useful, but accurate dosage becomes harder(especially where manual dexterity is compromised) ▪︎Any tablet needs around 60mL of water to wash it down and prevent adherence to the oesophageal mucosa large volume for a frail older person. ▪︎Some tablets (e.g. bisphosphonates) require even larger volumes ▪︎Multiple tablets, with different instructions (e.g. before/after food) are easily muddled up or taken in a suboptimal way ▪︎Some routes (e.g. topical to back) may be impossible without assistance ▪︎Absorption Many factors are different in older patients (↑ gastric pH, delayed gastric emptying, reduced intestinal motility and blood flow, etc.) Despite this, absorption of drugs is largely unchanged with age—exceptions include iron and calcium, which are absorbed more slowly ▪︎Distribution Some older people have a very low lean body mass, so if the therapeutic index for a drug is narrow (e.g. digoxin), the dose should be adjusted ▪︎There is often an ↑ proportion of fat, compared with water. ~This reduces the volume of distribution for water-soluble drugs, giving a higher initial concentration (e.g. digoxin). ~It also leads to accumulation of fat-soluble drugs,prolonging elimination and effect (e.g. diazepam) ~There is reduced plasma protein binding of drugs with age, which ↑ the free fraction of protein-bound drugs such as warfarin and furosemide.

~Hepatic metabolism Specific hepatic metabolic pathways (e.g. conjugation) are unaffected by age ~Reducing hepatic mass and blood flow can impact on overall function which slows metabolism of drugs (e.g. theophylline, paracetamol, diazepam,nifedipine) ~Drugs that undergo extensive first-pass metabolism (e.g. propranolol, nitrates)are the most affected by the reduced hepatic function ~Many factors interact with liver metabolism (e.g. nutritional state, acute illness, smoking, other medications, etc.)

~Renal excretion ~Renal function declines with age,which has a profound impact on the handling of drugs that are predominantly handled renally. Drugs, or drugs with active metabolites, that are mainly excreted in the urine include digoxin, gentamicin, lithium, furosemide, and tetracyclines. ~Where there is a narrow therapeutic index (e.g. digoxin, aminoglycosides),then dose adjustment for renal impairment is required ~Impaired renal function is exacerbated by dehydration and urinary sepsis both common in older patients. |

Prescribing ‘rules ■. Is it indicated? 2.Treatment of new symptom Some symptoms trigger a reflex prescription (e.g. constipation—laxatives;dizziness—prochlorperazine). Before starting a medication, consider: What is the diagnosis? (e.g. dizziness due to postural drop) Can something be stopped? (e.g. opioid analgesia causing constipation) Are there any non-drug measures? (e.g. ↑ fibre for constipation) Optimizing disease management For example: a diagnosis of cardiac failure should trigger consideration of loop diuretics, spironolactone, ACE inhibitors, and β-blockers. Ensure the diagnosis is secure before committing the patient to multiple drugs 3.Do not deny older patients disease-modifying treatments simply to avoid polypharmacy 4.Do not deny treatment because of potential side effects—while these may impact on functional ability or cause significant morbidity (e.g. low BP with β-blockade in cardiac failure) and need to be discontinued, this should usually be after a trial of treatment with careful monitoring. 5.Conversely, do not start treatment to improve mortality from a disease if the patient has limited life span for other reasons. 6.Preventative medication For example: BP and cholesterol lowering. Limited evidence base in older patients—be guided by biological fitness 7.Ensure the patient understands the rationale for treatment

■Are there any contraindications?▪︎Review past medical history (drug–disease interactions common) ▪︎Contraindications often relative, so a trial of treatment may be indicated, but warn the patient, document risk, and review impact (e.g. ACE inhibitors when there is renal impairment)

■Are there any likely interactions?Review the medication list Computer prescribing assists with drug–drug interactions, automatically flagging up potential problems ■ What is the best drug? •Choose the broad category of drug (e.g. which antihypertensive) by considering which will work best in this patient according to local and national guidelines,which is least likely to cause side effects (e.g. calcium channel blockers may worsen cardiac failure), and if there is any potential for dual action (e.g. a patient with angina could have a β-blocker for both angina and BP control). •Within each category of medication, there are many choices:Develop a personal portfolio of drugs with which you are very familiar •Guidelines and formularies will often dictate choices within hospital •Cost should be a consideration •Pharmaceutical companies will try to convince you of the benefits of a new brand. Unless this is a novel class of drug, it is likely that existing brands have a greater proven safety record with similar benefit. • Older patients have greater potential to suffer harm from new drugs and are unlikely to have been included in clinical trials. Time will tell if there are real advantages—in general, stick to what you know ► Never be the first (or last) of your peers to use a new drug. ■ What dose should be started? •‘Start low and go slow’In most cases, benefit is seen with drug initiation, further increments of benefit occurring with dose optimization (e.g. ACE inhibitors for cardiac failure where 1.25mg ramipril is better than 10mg with a postural drop) •However, do not undertreat—use enough to achieve the therapeutic goal (e.g.for angina prophylaxis, a β-blocker dose should be adequate to induce a mild bradycardia) ■. How will the impact be assessed?•Schedule follow-up, looking for:Efficacy of the drug (e.g. has bradykinesia improved with a dopamine agonist?). •Medication for less objective conditions (e.g. pain, cognition)requires careful questioning of the patient and family/carers •Any adverse events—reported by the patient spontaneously, elicited by direct questioning (e.g. headache with dipyridamole) or by checking blood tests where necessary (e.g. thyroid function on amiodarone) •Any capacity to ↑ the dose to improve the effect (e.g. ACE inhibitors in cardiac failure) ■ What is the time frame? •Many older patients remain on medication for a long time; 88% of all prescriptions in the over 65s are repeats; 60% of prescriptions are active for over 2 years, 30% over 5 years, and 6% over 10 years This may be appropriate (e.g. with antihypertensives) and if so, the patients hould be aware of this and seek an ongoing supply from the GP •Some drugs should never be prescribed long-term (e.g. prochlorperazine,night sedation) •Medication should be regularly reviewed and discontinued if ineffective or no longer indicated, e.g. some psychotropic medications (e.g. lithium, depot antipsychotics) were intended for long-term use at initiation, but the patient may have had no psychiatric symptoms for years (or even decades). They can contribute to falls, and cautious withdrawal may be indicated. An evidence-based comprehensive approach to medication review (e.g.STOPP START v2 criteria) can be useful. |

Taking a drug history 1]An accurate drug history includes the name, dose, timing, route, duration, and indication for all medication. Studies have suggested that patients will report their drug history accurately around half of the time, and this figure falls with ↑age. Reasons for problems arising ▪︎Inadequate information to the patient at the time of prescribing ▪︎Multiple medications ▪︎Multiple changes if side effects develop ▪︎Use of both generic and brand names ▪︎Variable doses over time (e.g. dopa agonists, ACE inhibitors) ▪︎Cognitive and visual impairment ▪︎Over-the-counter drugs ▪︎Useful sources of information The patient’s actual drugs—they will often bring them along in a bag to outpatients or when admitted.Many seasoned patients will carry a list of their current medication—written either by them or a healthcare professional.Computer-generated printouts of current medications from the GP.Increasingly available via shared electronic networksDosette® and Nomad® systems will incorporate information about the medication they containm A telephone call to the GP surgery will yield a list of active prescriptions (but not over-the-counter medication) Family members will often know about medication, especially if they help administer them Medical notes will often contain a list of medication at the last hospital attendance These can be extremely useful but have limitations. A prescription issued does not mean that it was necessarily dispensed or that the medication is being taken correctly and consistently. Previously prescribed medications may still be taken and patients may occasionally use another patient’s medication (e.g. a spouse). Good habits Every time a patient is seen (in clinic, day hospital, admission, etc.), take time. •Old drugs to be discarded (if necessary, retain them and return to pharmacy) •Concordance to be estimated (by looking at the date of dispensing and the number of tablets left) •Clarification of doses, timings, and rationale for treatment. •In a less-pressured setting (e.g. DH), it is useful to generate a list for the patient to carry with them. •Education of the patient and family where needed (e.g. reason for taking) |

|

|

Drug sensitivity •Altered sensitivity Many older patients will have altered sensitivity to some drugs, e.g.:Receptor responses may vary with age. ~Alterations in the function of the cellular sodium/potassium pumps may account for the ↑ sensitivity to digoxin seen in older people. ~↓ β-adrenoceptor sensitivity means that older patients mount less of a tachycardia when given agonists (e.g. salbutamol) and may become less bradycardic with β-blockers. ~Altered coagulation factor synthesis with age leads to an ↑ sensitivity to the effects of warfarin. ~The ageing CNS shows ↑ susceptibility to the effects of many centrally acting drugs (e.g. hypnotics, sedatives, antidepressants, opioid analgesia,antiparkinsonian drugs, and antipsychotics) •Adverse reactions Certain adverse reactions are more likely in older people, because of this altered sensitivity: Baroreceptor responses are less sensitive, making symptomatic hypotension more likely with antihypertensives. Thirst responses are blunted, making hypovolaemia due to diuretics more common. Thermoregulation is blunted, making hypothermia more likely with prolonged sedation. |

Drugs that may require dose adjustment in older patients ▪︎Despite the variations in drug handling, most drugs have a wide therapeutic index, and there is no clinical impact. Only drugs with a narrow therapeutic index or where older patients may show very marked ↑ sensitivity may require dose alteration: ACE inhibitors Aminoglycosides (dose determined by weight, and reduced if impaired renal function) Diazepam (start with 2mg dose) Digoxin (low-body-weight older patients rarely require >62.5 micrograms maintenance dose) Opiates (start with 1.25–2.5mg morphine to assess impact on CNS) Oral hypoglycaemics (↑ sensitivity to hypoglycaemia with ↓ awareness—avoid long-acting preparations such as glibenclamide, and start with lower doses of shorter-acting drugs, e.g. gliclazide 40mg) Warfarin (load more cautiously) |

Adverse drug reactions More common and complex with ↑ age—up to three times more frequent in theover 80s. Drug reactions account for considerable morbidity, mortality, and hospital admissions (1 in 25 hospital admissions may result from avoidable drug adverse reactions). Older people are not a homogeneous group, and many will tolerate medications as well as younger ones, but a number of factors contribute to the ↑frequency: •Altered drug handling and sensitivity occur with age, made worse by poor appetite, nutrition, and fluid intake. •Frailty and multiple diseases make drug–disease interactions more common,e.g.: ~Anticholinergics may precipitate urine retention in a patient with prostatic hypertrophy ~Benzodiazepines may precipitate delirium in a patient with dementia. These relationships become even more complex when the large numbers of drugs that are prescribed for multiple conditions interact with the diseases, as well as with each other, e.g. an osteoporotic patient is prescribed a bisphosphonate, then sustains a vertebral crush fracture and is given a non-steroidal which exacerbates gastric irritation and causes a gastrointestinal bleed. •Errors in drug taking make adverse reactions more likely. Mistakes ↑ with: □↑ age↑ numbers of prescribed drugs (20% of patients taking three drugs will make errors, rising to 95% when ten or more drugs are taken) □Cognitive impairment □Living alone Strategies to minimize adverse drug reactions □Consider possible drug–drug and drug–disease interactions when ever a new drug is started. Some drugs are associated with high rates of drug–drug interactions, e.g.warfarin, amiodarone, SSRIs, antifungals, digoxin, phenytoin, and erythromycin. □For every new problem, consider if an existing medication could be the cause. ~Try to avoid the so-called prescribing cascade where side effects are treated with a new prescription, rather than discontinuing the offending drug. □If multiple medications are possible culprits, then stop one at a time and watch for improvement. □Optimize concordance/adherence □Use extreme caution at times of care transfer medicines reconciliation is important. |

|

ACE inhibitors Common indications include ▪︎BP control, ▪︎vascular risk reduction, ▪︎heart failure,and ▪︎diabetic nephropathy. Cautions Renal disease ▪︎Use ACE inhibitors with extreme caution if there is a known history of renal artery stenosis, as renal failure can be precipitated. If the clinical suspicion of this is high (renal bruit, uncontrolled hypertension that is unexplained), then consider investigating for renal asymmetry with an ultrasound before starting treatment. Renal impairment per se is not a reason to withhold ACE inhibitors (indeed they are effective treatment for some types), although the dose may need to be reduced. Monitor renal function before and after treatment. Sudden deterioration may indicate renal artery stenosis, and the ACE inhibitor should be stopped pending investigation. If a patient becomes unwell (dehydrated, septic, etc.), they may need temporary withdrawal of the ACE inhibitor—provide your patient with ‘sickday rules’ Hypotension. ▪︎Older patients are more prone to postural hypotension. Check BP lying and standing, and ask about postural symptoms (e.g. light-headedness). The risk of hypotension is greater with volume depleted patients, e.g. those on high-dose diuretics, on renal dialysis, dehydrated from intercurrent illness, or in severe cardiac failure. □Correct dehydration before initiation, where possible. ACE inhibitor-induced hypotension is common in patients with severe aortic stenosis and, although beneficial in this condition, should be started slowly‘Start low and go slow.’ Monitor carefully •Cough Many ACE inhibitors cause a persistent dry cough. Always warn the patient about this, as it can cause considerable distress. Fore warned is forearmed, and many patients will be prepared to accept this side effect if the ACE inhibitor is the best choice for them. Changing to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) removes the cough in most cases. •Hyperkalaemia There is a risk of hyperkalaemia when ACE inhibitors are used with potassium-sparing diuretics, e.g. spironolactone.Be aware, and monitor electrolytes. Most tolerate a potassium level of up to5.5mmol/L. The tendency to hyperkalaemia can be useful in patients who are also on potassium-losing diuretics (e.g. furosemide), as the two may balance each other out overall hypokalaemia is more common in patients with heart failure. |

Analgesia Older patients are more likely to suffer chronic pain than younger ones, owing tothe ↑ frequency of conditions such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, etc.Pain management is more challenging, and a standard ‘pain ladder’ approachis not always useful because of the altered sensitivity of the older patient tocertain classes of analgesic medication.Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsIncludes aspirin (especially at analgesic doses).Potential problemsFluid retention causing worsening hypertension, cardiac failure, and ankleswellingRenal toxicity—risk of acute tubular necrosis (ATN), exacerbated byintercurrent infection or dehydrationPeptic ulceration and gastrointestinal bleeding—there is an ↑ risk with ↑ age,and the bleeds tend to be more significant► The number of older patients requiring hospitalization because of NSAID-induced deterioration in renal or cardiac function actually exceeds the numberwith gastrointestinal bleeds.Age itself is probably not an independent risk factor for most complications ofNSAID treatment, but factors such as comorbidities, co-medications,hydration, nutritional status, and frailty are linked to an ↑ risk, all of which aremore common with advancing ageGuidance for use in older patientsNSAIDs should be used with extreme caution in older patients and avoidedaltogether in the very frailShould be given for a short period onlyUse low-dose moderate potency NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen 0.6g/day)Avoid using two NSAIDs together (this includes low-dose aspirin)Consider co-prescription of a gastric-protective agent (e.g. omeprazole) forthe duration of the therapyAvoid using ACE inhibitors and NSAIDs together—they have opposingeffects on fluid handling and are likely to cause renal toxicity in combinationOpioid analgesia•••••Wide range of drugs sharing many common features, but with qualitative andquantitative differencesPotential problems include constipation, nausea and vomiting, anorexia,confusion, drowsiness, and respiratory depressionGuidance for use in older patientsMost of these are dose-dependent, and careful up-titration will obtain the rightbalance of analgesic effect and adverse effectsConstipation is common (worse in older people) but can be managed withgood bowel careMost adverse effects are reversible once the medication is reduced ordiscontinued |

•••••••••SteroidsOral steroids (usually prednisolone) are given for many conditions in olderpatients, commonly COPD exacerbation, PMR, rheumatoid arthritis, and colitis.Treatment may be long-term. Although the benefits of treatment usuallyoutweigh the risks, awareness of these can minimize harm. Discuss likely sideeffects with patients and carers.CautionsOsteoporosis—this is most marked in the early stages of treatment. Olderpeople will have diminishing bone reserves anyhow, and all steroid-treatedolder patients should be offered bone protection at the outset, unless thecourse is certain to be very short (e.g. <2 weeks). This should consist of dailycalcium and vitamin D, along with a bisphosphonate (weekly preparations,e.g. alendronate 70mg, improve concordance)Steroids can precipitate impaired glucose tolerance or frank diabetes. Monitorsugar levels periodically (e.g. weekly capillary blood sugar or urinalysis) in allsteroid users. Steroids worsen control in known diabetics, necessitating morefrequent monitoringHypertension may develop because of the mineralocorticoid effect ofprednisolone, and this should be checked for regularlySkin changes occur and are particularly noticeable in older patients with lessresilient skin. Purpura, bruising, thinning, and ↑ fragility are commonMuscle weakness occurs with prolonged use, predominantly proximal indistribution. This leads to problems rising from chairs, climbing stairs, etc.and may be the final straw for a frail older person with limited physicalreserve (see ‘Muscle symptoms’, pp. 480–481)There is an ↑ susceptibility to infections on steroids, and the presentation maybe less acute, making diagnosis more difficult. Candidiasis (oral and genital)is particularly common and should be treated promptlyHigh doses (as used in the treatment of giant cell arteritis (GCA)) can causeacute confusion and sleep disturbance, and older people are particularlyprone. Give steroids in the morning, if possibleCataracts may develop with long-term steroid use. If vision declines, look forcataracts with an ophthalmoscope and consider specialist referralPeritonitis may be masked by steroid use—the signs being less evidentclinically. Have a higher index of suspicion of occult perforation in a steroid-treated older patient with abdominal pain. There is also an association•••••between steroid use and peptic ulceration, particularly in hospitalized patientsAdrenocortical suppression means that the stress response will be diminishedin chronic steroid users. If such a patient becomes acutely unwell (e.g. septic),the exogenous steroid dose will need to be temporarily ↑ (e.g. double the usualoral dose, replace with intramuscular (im) hydrocortisone if unable to take bymouth). Counsel the patient with ‘sick day rules’. Suppression can continuefor months after stopping chronic steroids; have a low threshold for ‘covering’acute illnessStopping treatmentMany patients are on fairly low doses of steroids for a long period. It can bedifficult to completely tail the dose, as steroid withdrawal effects (fevers,myalgia, etc.) can often be mistaken for disease recurrence, and this often needsto be done very slowly (perhaps reducing by as little as 1mg a month). There isno such thing as a ‘safe’ dose of steroid so, for every patient you see on steroids,ask the following:Can the dose be reduced?Could a steroid-sparing agent (e.g. azathioprine) be used instead?Is the patient taking adequate bone protection?What is the BP and blood glucose? |

|

Warfarin Common indications range from ■absolute (PE, DVT, artificial heart valve replacement) to ■relative (stroke prophylaxis in AF). •Increasingly direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are being used instead, but warfarin remains in common use.

Cautions □Risk is ↑ if the patient is unable to take medications reliably, so it is not suitable without supervision for cognitively impaired patients or those who self-neglect. If there is an absolute indication, then consider supervised therapy (by spouse, family, or carers via a dispensing system) or (rarely) a course of low-molecular-weight heparin instead. □Risk is higher if there is a high probability of trauma, e.g. recurrent falls □Excess alcohol consumption is associated with poor concordance and falls. Liver enzymes are induced, making control of anticoagulation more difficult. Highly variable intake is especially problematic. □Comorbidity may ↑ sensitivity to warfarin (e.g. abnormal liver function,congestive cardiac failure) and should be screened for GPs will often be good judges of risk—consider discussing borderline cases. Side effects •Bleeding is the major adverse event, ranging from an ↑ tendency to bruise to major life-threatening bleeds. •The most significant include intracerebral haemorrhage and gastrointestinal blood loss. Warfarin does not cause gastric irritation but may accelerate blood loss from pre-existing bleeding sources. •Ask carefully about history of non-steroidal use (including aspirin) and gastrointestinal symptoms (upper and lower). If any are present, then quantify the risk with further testing—FBC and iron studies might indicate occult blood loss. If warfarin is not essential, then a full gastrointestinal work-up may be appropriate before starting in fitter patients. •Nose bleeds are common in older patients and may become more significant on warfarin. Often due to friable nasal vessels that are amenable to treatment by ENT surgeons, so reducing the risk of epistaxis on warfarin.

What to do when the INR is too high Always look for the reason why the INR became elevated, and correct this factor. If there is no sign of bleeding, then stop warfarin and monitor the INR as it falls. If the INR >8 but there is no bleeding, a small dose of vitamin K (0.5–2.5mg)can be given to partially reverse the INR. ■Do not give vitamin K routinely, as control of anticoagulation will be made more difficult for weeks afterwards. ■If there is bleeding, then warfarin needs reversing with vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma. ■For life-threatening bleeds (e.g. intracerebral haemorrhage), prothrombin complex concentrate can be used for rapid reversal. ► If a patient bleeds at target INR, always consider the possibility of an underlying serious disease, e.g. bladder or gastrointestinal malignancy. |

|

Direct oral anticoagulants This class of drugs (DOACs) is also known as novel/new oral anticoagulants(NOACs) and is increasingly being used in place of warfarin as evidence of non-inferiority emerges.Compared to warfarin, the main advantages are •Immediate onset of action •No need for INR monitoring •Reduced rates of bleeding (especially intracerebral) •No food or alcohol interactions The main disadvantages include •Harder to reverse—although short duration of action means that the drug clears from the system quickly, and reversal agents are in development •Dose needs adjustment for renal impairment •Some agents require twice-daily dosing •Short duration of action means that any missed doses render the patient unanticoagulated •Less familiar medications, and prescribers should note numerous drug interactions with commonly used drugs (e.g. tramadol, clarithromycin) •Limited long-term outcome data, particularly in the older patient •Not licensed for metallic heart valve thromboprophylaxis Higher cost ▪︎When to use?Patients who have been stable on warfarin should not be changed. Patients in whom it is unacceptable/very difficult to monitor INR, or who have an unstable INR, would be good candidates for a DOAC. When initiating anticoagulation, discuss options with patients and be guidedby local policy ► If a patient is not a candidate for warfarin, it is unlikely they will be ‘safe’ on a DOAC, and careful risk/benefit analysis is always needed (e.g. a frequent faller will be no safer on a DOAC than on warfarin). |

|

|

Proton pump inhibitors •PPIs (e.g. omeprazole, lansoprazole) are very effective in reducing gastric acid secretion and therefore in treating peptic ulcers and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). They are perceived as very safe drugs but are not without problems. The combination of effectiveness and safety has led to them being one of the most commonly prescribed drug classes. •However, PPIs are often prescribed without an appropriate indication, or are initiated appropriately but not discontinued after a treatment course. Overall, over 50% of PPI use is unnecessary.

Side effects Common side effects are Headache Nausea Diarrhoea Constipation Infrequent idiosyncratic reactions include acute interstitial nephritis, erythema multiforme, pancreatitis, and microscopic colitis Hyponatraemia and hypomagnesaemia can occur—consider checking in non-specific presentations. ▪︎Hydrochloric acid aids protein digestion and absorption of vitamin B12 and calcium and is active against pathogens. •PPI use is associated with: □Community and hospital incidence of CDAD and ↑ likelihood of recurrence □Enteric bacterial infections (e.g. Salmonella, Campylobacter) □Community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia □Long-term use is associated with higher rates of hip fracture, possibly caused by altered calciumabsorption ■Interactions There are a few important interactions: •The effects of phenytoin and warfarin are enhanced •The effects of clopidogrel are reduced •Plasma concentrations of digoxin are ↑ slightly

Appropriate prescribing •Always specify the indication for treatment and its intended duration In GORD, always first address non-drug factors (obesity, alcohol), and consider the use of less potent acid suppression (e.g. H2 antagonists such as ranitidine) •Transient dyspepsia or occasional heartburn are inadequate indications for long-term PPI treatment. In 1° care, review the need for the drug periodically. In 2° care, be careful not to extend an initial appropriate PPI prescription for prophylaxis against gastrointestinal bleeding. When antibiotics are prescribed in hospital, suspend the PPI prescription to reduce the risk of CDAD. In (confirmed or possible) CDAD, stop PPIs. |

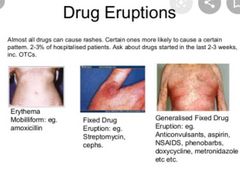

HOW TO . . . Manage drug-induced skin rashes Common side effect in older patients—thought to be due to altered immune function. Rarely life-threatening but cause considerable distress. Make the diagnosis Variable in appearance, but most commonly toxic erythema—symmetrical, erythematous, itchy rash, trunk > extremities, lesions may be measles-like or urticarial, or resemble erythema multiforme ▪︎Certain drugs may produce predictable eruptions: □Acneiform rash with lithium □Bullous lesions with furosemide □Target lesions with penicillins and phenytoin □Psoriasis-like rash with β-blockers □Urticaria with penicillin, opiates, and aspirin □Fixed drug eruption (round, purple plaques recurring in the same spot)with paracetamol, laxatives, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines □Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare, serious reaction to drugs such as non-steroidals, allopurinol, and phenytoin. The skin appears scalded, and large areas of the epidermis may shear off, causing problems with fluid and electrolyte balance, thermoregulation, and infection

▪︎Take a careful drug history to elicit a temporal relationship to medication administration, e.g. within 3 days of starting a new drug (may be as long as 3 weeks) or becoming worse every morning after a regular drug is given. ▪︎Stop the drug ▪︎Stop multiple medications one at a time (stop drugs started closest to the onset of the rash first), and watch for clinical improvement. ▪︎May get slightly worse before improving ▪︎Usually clears within 2 weeks ▪︎Advise the patient to avoid the drug in the future. ▪︎Soothe the skin Emollients, cooling agents (e.g. calamine), and weak topical steroids may help. ▪︎Oral anti histamines are often given, with variable success. ▪︎Sedating antihistamines (e.g. hydroxyzine) may help sleep. ▪︎Treat the complications •More likely if extensive and prolonged Risks include: Hypothermia Hypovolaemia 2° infection ► Consider dermatology referral if not improving after 2 weeks off the suspected drug. |

Breaking the rules A great deal of prescribing in geriatric practice relies on individually tailored assessment and pragmatic decision-making, as inter-individual variation ↑ with age. In addition, trials often exclude older subjects, making the evidence base an extrapolation. While what is described in the preceding pages is appropriate for many, there are times when ‘rules must be broken’ in the best interests of the individual patient. •This requires careful consideration of risks and benefits; the patient should usually be reviewed to assess the impact of the decision. ▪︎Polypharmacy can cause problems but is sometimes appropriate—depriving patients of beneficial treatments because they are old, or already on multiple other medications, can also be wrong. In a recent study of medication changes during a geriatric admission, the total number of drugs was the same at admission and discharge, but they had often been changed. • In other words, there was active evaluation of medications going on the goal being not just to limit the number of drugs, but also to optimize and individually tailor treatment. •Where side effects are very likely, but the drug is definitely indicated, then it may be appropriate to co-prescribe something to treat the expected adverse effect, e.g.: Steroids and bisphosphonates Opiates and laxatives Furosemide and a potassium-sparing diuretic (or an ACE inhibitor) Non-steroidals and a gastric protection agent While certain disease–drug interactions are very likely and should be avoided,others may be an acceptable risk. For example: ▪︎β-blockers:Are to be used with caution with asthma, yet they have such a good impacton cardiovascular risk reduction that these cautions are not absolute. Often‘asthma’ is, in fact, COPD with little β-receptor reactivity, so cautious β-blockade initiated in hospital while monitoring the lung function may be appropriate. ▪︎In patients with peripheral vascular disease, they can cause a small reduction in walking distance, but this risk is usually outweighed by the reduction in the risk of cardiac death. ▪︎Fludrocortisone (for postural hypotension) will worsen supine hypertension and cause ankle swelling. But if postural symptoms are severe, then it may be appropriate to accept hypertension and the associated risk •Amlodipine may worsen ankle swelling in a patient with chronic venous insufficiency, but if this is the best way of controlling hypertension, it may be appropriate to accept a cosmetic problem. |

|

|

Neurology ▪︎The ageing brain and nervous system ▪︎Tremor ▪︎Neuropathic pain/neuralgia ▪︎HOW TO . . . Treat neuralgia ▪︎Parkinson’s disease: presentation ▪︎Parkinson’s disease: management ▪︎HOW TO . . . Manage a patient with Parkinson’s disease who cannot take oral medication ▪︎HOW TO . . . Treat challenging symptoms in Parkinson’s disease ▪︎Diseases masquerading as Parkinson’s disease ▪︎Epilepsy ▪︎Epilepsy: drug treatment ▪︎Neuroleptic malignant syndrome ▪︎Motor neuron disease ▪︎Peripheral neuropathies ▪︎Subdural haematoma ▪︎Sleep and insomnia ▪︎HOW TO . . . Use benzodiazepines for insomnia ▪︎Other sleep disorders |

1Essential tremor Clinical features Management 2 PARKINSON'S poor prognostic features |

|

|

The ageing brain and nervous system As in other systems, intrinsic ageing (occurs in all) is often hard to distinguish from extrinsic ageing mechanisms (caused by disease processes). Histological changes in the brain include: Each neuron has fewer connecting arms (dendrites) Around 20% of brain volume and weight are lost by the age of 85 There is deposition of pigment (lipofuscin) in the cells and oxidative damage in mitochondria. The presence of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles ↑ with age, but they are not diagnostic of dementia. |

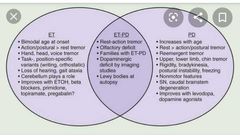

Tremor Tremor is more common with ↑ age. It can be disabling and/or socially embarrassing. It is important to try to make a diagnosis, as treatment is available in some cases. Examine the patient first at rest and distracted (relaxed with arms supported on the lap, count backwards from 10), then with outstretched hands, and finally during movement (pointing or picking up a small object). Tremors fall roughly into three categories: Rest tremor—disappears on movement and is exaggerated by movement of the contralateral side of the body. Most common cause—Parkinson’s disease. It is usually associated with ↑ tone Postural tremor—present in outstretched limbs, may continue during action but disappears at rest. Most common cause—benign essential tremor Action tremor—exaggerated with movement. When the tremor is maximal at extreme point of movement, it is called an intention tremor. Most common cause—cerebellar dysfunction Benign essential tremor The classic postural tremor of old age, worse on action (e.g. static at rest but spills tea from tea cup), may have head nodding (titubation) or jaw/vocal tremor, legs rarely affected. May be asymmetrical About half of the cases have a family history (autosomal dominant) Presents in middle age, occasionally earlier, and worsens gradually. Often more socially embarrassing than physically impairing. Improved by alcohol, gabapentin, primidone, and β-blockers, but these are often unacceptable treatments in the long term. Worth considering β-blockers as the first choice in treatment with coexistent hypertension. Weighted wristbands can reduce tremor and improve function. Cerebellar dysfunction The typical intention tremor is associated with ataxia. Acute onset is usually vascular in older patients. Subacute presentations occur with tumours (including paraneoplastic syndrome), abscesses, hydrocephalus, drugs (e.g. anticonvulsants) hypothyroidism, or toxins Chronic progressive course is seen with: ▪︎Alcoholism (due to thiamine deficiency always give thiamine 100mg once daily (od) orally (po) or iv preparation if in doubt; it might bereversible) ▪︎Anticonvulsant (e.g. phenytoin—may be irreversible if severe, more common with high plasma levels but can occur with long-term use at therapeutic levels) Paraneoplastic syndromes (anti-cerebellar antibodies can be found, e.g.anti-Yo and anti-Hu found in cancer of the ovary and bronchus) Multiple sclerosis Idiopathic cerebellar atrophy Many cases defy specific diagnosis. Consider multisystem atrophy |

|

|

|

Neuropathic pain/neuralgia This describes pain originating from nerve damage/inflammation. It is often very severe and debilitating and seems to be more common in older people. The pain is usually sharp/stabbing and is often intermittent, being precipitated by things like movement and cold.

1.Post-herpetic neuralgia Severe burning and stabbing pain in a division of nerve previously affected by shingles. Shingles and subsequent persisting neuralgia is much more common in older patients. Pain may be triggered by touch or temperature change. May go on for years, be difficult to treat, and have major impact on quality of life. Prevent by vaccination to reduce risk/severity of shingles. If shingles develops, starting antivirals within 72h reduces neuralgia incidence.

2.Trigeminal neuralgia Severe unilateral stabbing facial pain, usually V2 and V3, rather than V1. Triggers include movement, temperature change, etc. Time course—years with relapse/remission. Depression and weight loss can result. Differential diagnoses include temporal arteritis (TA), toothache, parotitis, and temporomandibular joint arthritis ▪︎Consider neuroimaging, especially if bilateral or if there are physical signs, i.e. sensory loss or other cranial nerve abnormality suggestive of 2° trigeminal neuralgia.

Neuralgia can also occur with 3.Malignancy 4.Cord compression 5.Neuropathy |

HOW TO Treat neuralgia ○This can be very debilitating, and treatment is difficult. There is often coexistent depression, so always think of this and treat appropriately. Simple measures include □Distraction □Relaxation techniques □Allaying fears (usually about a serious underlying pathology) □Acupuncture □Heat/cold treatment □Osteopathy/massage (to reduce associated muscle spasm) □Use of TENS machines Support groups, □Medications •Topical treatments, e.g. lidocaine, capsaicin •Traditional analgesics (paracetamol, NSAIDs, opiates), although these are usually not very effective. •Anti-spasticity drugs, e.g. baclofen. Used especially in trigeminal neuralgia,they treat any muscle spasm that exacerbates the pain. ■Mainstay of treatment is the neuromodulating drugs which may give superior pain control but often have important side effects. Examples include: □Antidepressants with neuroadrenergic modulating abilities, e.g.amitriptyline, duloxetine. Start with a low dose and titrate up slowly. Eventual doses may be similar to those used in younger patients. □Anticonvulsants, e.g. •gabapentin, pregabalin (post-herpetic neuralgia) or •carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproate (trigeminal neuralgia). Start witha low dose and titrate up slowly. The main side effects from these drugs are sedation and confusion, and reaching a therapeutic dose may be limited by this problem. Other options □Nerve blocks or spinal stimulation, which can usually be accessed via aspecialist pain clinic □ Surgery, e.g. nerve decompression, or treatment with heat or lasers. May provide relief but can result in scarring and numbness. |

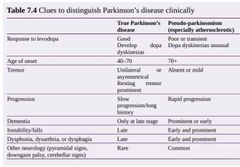

Parkinson’s disease: •A common idiopathic disease (prevalence 150/100 000) associated with inadequate dopamine neurotransmitter in the brainstem. •There is loss of neuronsand Lewy body formation in the substantia nigra. •The clinical syndrome is distinct from Lewy body dementia but they are extremes of a clinical spectrum of disease. Presentation The clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease is based on the UK Parkinson’sdisease brain bank criteria and should include: 1.Bradykinesia ~slow to initiate and carry out movements, ~expressionless face, ~fatigability of repetitive movement 2.Plus at least one of the following: ▪︎Rigidity (cogwheeling = tremor super imposed on rigidity) ▪︎Tremor (‘pin-rolling’ of hands—worse at rest) ▪︎Postural instability Other clinical features: ▪︎Gait disorder (small steps) ▪︎Usually an asymmetrical disease ▪︎No pyramidal or cerebellar signs, but reflexes are sometimes brisk. ▪︎Non-motor symptoms are common and should be asked about. |

|

|

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease ▪︎Depression (treat appropriately) ▪︎Anosmia (may be an early pre-motor feature) ▪︎Psychosis (may relate to medications; avoid typical antipsychotics, as they may worsen the motor features; atypicals such as quetiapine can be tried) ▪︎Dementia and hallucinations can occur in late stages, but drug side effects can cause similar problems. If features suggest Lewy body dementia, a trial of anticholinesterases may be warranted. ▪︎Sleep disturbance ~treat restless legs; ~review medications; ~advise about driving if sudden-onset sleep; ~daytime hypersomnolence may be treated with modafinil) ▪︎Falls (usually multifactorial; ▪︎Autonomic features are common in older patients. They should be sought and actively managed: ~Weight loss ~Dysphagia ~Constipation ~Erectile dysfunction ~Orthostatic hypotension ~Excessive sweating ~Drooling Investigations ▪︎Diagnosis is clinical and, once suspected, should be reviewed by a Parkinson’sdisease specialist. ▪︎Trials of treatment may be done, with review of the diagnosis if there is no improvement, but single-dose levodopa ‘challenge’ tests are no longer performed. ▪︎Brain imaging (e.g. CT) can be used to illustrate other conditions that may mimic Parkinson’s disease (e.g. vascular disease) ▪︎Specialist scans are becoming more widely used to assist diagnosis (e.g.consider123I-FP-CIT single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT),commonly known as DatSCAN™ after the radiolabelled solution used). ▪︎Patients with essential tremor, Alzheimer’s disease, or drug-induced Parkinsonism have normal scans. |

•Parkinson’s disease: management Should be overseen by a Parkinson’s disease specialist clinic. Drugs ▪︎It is not possible to identify a universal first-choice drug therapy for either early Parkinson’s disease or adjuvant drug therapy for later stages. ▪︎Consider the short- and long-term benefits and risks of each treatment, along with lifestyle and clinical factors. Discussion with the patient is key. ▪︎Initiation treatment is started with one of the following: 1.Levodopa plus a decarboxylase inhibitor (prevents peripheral breakdown of drug) (co-beneldopa/co-careldopa). Start low and titrate to symptoms 2.Dopamine agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole, rotigotine). Psychiatric side effects, postural hypotension, and nausea may limit therapy 3.MAOI (selegiline, rasagiline). These drugs have many interactions with antidepressants and should be used with care by a specialist. ■Adjuvant treatment may be needed as the disease progresses. ▪︎Firstly, ↑ doses or add a second agent from the list already given; ▪︎then consider: □Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor (entacapone). Will smoothe fluctuations in plasma levodopa concentrations. Must be given with levodopa. Stains urine orange □Amantadine—weak dopamine agonist which can reduce dyskinetic problems. □Apomorphine—s/c injections. Specialist treatment— rarely useful in older patients □Anticholinergics (trihexyphenidyl, orphenadrine) are mild antiparkinsonian drugs, rarely useful in elderly patients due to severe psychiatric side effects. They do have a beneficial effect on tremor and are possibly the drug of choice where tremor is more of a problem than bradykinesia. Surgery □Ablation (e.g. pallidotomy) and stimulation (electrode implants) used in highly selected populations. Older patients often excluded due to high operative risk and rigorous exclusion criteria (e.g. cognitive impairment). Other therapeutic options ▪︎Patients and carers benefit from regular review by a specialist doctor or nurse.Many services now have specialist Parkinson’s disease nurses. ▪︎A course of PT can be helpful to boost mobility and reduce falls. ▪︎OT plays a vital role in aids and adaptations for disability. ▪︎SALTs, along with dieticians, can help when swallowing becomes a problem. ▪︎Inpatient assessment is rarely helpful, as hospital routines can rarely match home treatment and some patients deteriorate in hospital. Parkinson’s UK ( http://www.parkinsons.org.uk) has plenty of information and advice for patients and carers |