![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

46 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

- 3rd side (hint)

|

Barrett Esophagus Is Replacement of Esophageal Squamous Epithelium by Columnar Epithelium

Barrett esophagus is a result of chronic gastroesophageal reflux. Its incidence has been increasing in recent years, particularly among white men. This disorder occurs in the lower third of the esophagus but may extend higher. There is a slight male predominance and a more than twofold increased risk for Barrett esophagus among smokers. Patients with Barrett esophagus are placed in a regular surveillance program to detect early microscopic evidence of dysplastic mucosa. |

A. The presence of the tan tongues of epithelium interdigitating with the more proximal squamous epithelium is typical of Barrett esophagus. B. The specialized epithelium has a villiform architecture and is lined by cells that are foveolar gastric type cells and intestinal goblet type cells.

|

|

Esophagus and upper stomach

|

Achalasia Features Impaired Function of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter

Achalasia, at one time termed cardiospasm, is characterized by failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax in response to swallowing and absence of peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. As a result of these defects in both the outflow tract and the pumping mechanisms of the esophagus, food is retained within the esophagus and the organ hypertrophies and dilates conspicuously. Achalasia is associated with loss or absence of ganglion cells in the esophageal myenteric plexus. Degenerative changes in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and extraesophageal vagus nerves have also been described. Ganglion cell loss may be accompanied by chronic inflammation. In Latin America, achalasia is a common complication of Chagas disease, in which the ganglion cells are destroyed by the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi. Dysphagia, occasionally odynophagia, and regurgitation of material retained in the esophagus are common symptoms of achalasia. Squamous carcinoma is also a complication. Treatment is by dilation or surgical myotomy, which can lead to gastroesophageal reflux. |

Esophagus and upper stomach of a patient with advanced achalasia. The esophagus is markedly dilated above the esophagogastric junction, where the lower esophageal sphincter is located. The esophageal mucosa is redundant and has hyperplastic squamous epithelium.

|

|

Esophagus--Barium Swallow

|

Schatzki mucosal ring

|

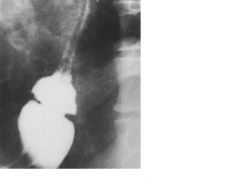

Schatzki mucosal ring. A contrast radiograph illustrates the lower esophageal narrowing.

|

|

Esophagus

|

Esophageal varices are dilated veins immediately beneath the mucosa (Fig. 13-6) that are prone to rupture and hemorrhage (also see Chapter 14). They arise in the lower third of the esophagus, virtually always in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. The lower esophageal veins are linked to the portal system through gastroesophageal anastomoses. If portal system pressure exceeds a critical level, these anastomoses become prominent in the upper stomach and lower esophagus. When varices are greater than 5 mm in diameter, they are prone to rupture, leading to life-threatening hemorrhage. Reflux injury or infective esophagitis can contribute to variceal bleeding.

|

Esophageal varices. A. Numerous prominent blue venous channels are seen beneath the mucosa of the everted esophagus, particularly above the gastroesophageal junction. B. Section of the esophagus reveals numerous dilated submucosal veins.

|

|

Esophagus

|

The most common presenting complaint is dysphagia, but by this time most tumors are unresectable. Patients with esophageal cancer are almost invariably cachectic, owing to anorexia, difficulty in swallowing, and the remote effects of a malignant tumor. Odynophagia occurs in half of patients and persistent pain suggests mediastinal extension of the tumor or involvement of spinal nerves. Compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve produces hoarseness and tracheoesophageal fistula is manifested clinically by a chronic cough. Surgery and radiation therapy are useful for palliation, but the prognosis remains dismal. Many patients are inoperable and of those who undergo surgery, only 20% survive for 5 years.

|

Esophageal carcinoma. A. Squamous cell carcinoma. There is a large ulcerated mass present in the squamous mucosa with normal squamous mucosa intervening between the carcinoma and the stomach. B. Adenocarcinoma. There is a large exophytic ulcerated mass lesion just proximal to the gastroesophageal junction. The well-differentiated adenocarcinoma was separated from the most proximal squamous epithelium by a tan area representing Barrett esophagus.

|

|

Endoscopic Stomach

|

Acute hemorrhagic gastritis is characterized grossly by widespread petechial hemorrhages in any portion of the stomach or regions of confluent mucosal or submucosal bleeding (Fig. 13-10). Lesions vary from 1 to 25 mm across and appear occasionally as sharply punched-out ulcers. Microscopically, patchy mucosal necrosis, which can extend to the submucosa, is visualized adjacent to normal mucosa. Fibrinous exudate, edema and hemorrhage in the lamina propria are present in early lesions. Necrotic epithelium is eventually sloughed, but deeper erosions and hemorrhage may be present. In extreme cases, penetrating ulcers may reach the serosa.

Symptoms of acute hemorrhagic gastritis range from vague abdominal discomfort to massive, life-threatening hemorrhage, or clinical manifestations of gastric perforation. Patients with gastritis induced by aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents may be seen with hypochromic, microcytic anemia caused by undetected chronic bleeding. However, in patients with a severe underlying illness, the first sign of stress ulcers may be exsanguinating hemorrhage. Treatment with antacids and histamine-receptor antagonists has proved useful. |

Erosive gastritis. This endoscopic view of the stomach in a patient who was ingesting aspirin reveals acute hemorrhagic lesions.

|

|

Stomach

|

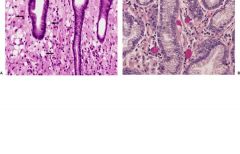

ATROPHIC GASTRITIS: This condition is characterized by prominent chronic inflammation in the lamina propria. Occasionally, lymphoid cells are arranged as follicles, an appearance that has led to an erroneous diagnosis of lymphoma, especially in patients with H. pylori infection (see below). Involvement of gastric glands leads to degenerative changes in their epithelial cells and ultimately to a conspicuous reduction in the number of glands (thus the name atrophic gastritis; Fig. 13-11). Eventually, inflammation may abate, leaving only a thin atrophic mucosa, in which case the term gastric atrophy is applied.

INTESTINAL METAPLASIA: This lesion is a common and important histopathologic feature of both autoimmune and multifocal types of atrophic gastritis. In response to injury of the gastric mucosa, the normal epithelium is replaced by one composed of cells of the intestinal type (see Fig. 13-11C). Numerous mucin-containing goblet cells and enterocytes line cryptlike glands. Paneth cells, which are not normal inhabitants of the gastric mucosa, are present. Intestinal-type villi may occasionally form. The metaplastic cells also contain enzymes characteristic of the intestine but not of the stomach (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, aminopeptidase). |

Autoimmune gastritis. A. Normal gastric antrum. B. In autoimmune gastiritis, the gastric mucosa shows chronic inflammation within the lamina propria. The diminished number of antral glands indicates atrophy. C. The atrophic glands show goblet cells (arrows), and there is chronic inflammation in the lamina propria.

|

|

Stomach

|

H. pylori gastritis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the antrum and body of the stomach caused by H. pylori and occasionally by Helicobacter heilmannii. It is the most common type of chronic gastritis in the United States. The organism causes one of the most frequent chronic infections. H. pylori infection is also strongly associated with peptic ulcer disease of the stomach and duodenum (see below).

Helicobacter species are small, curved, gram-negative rods (Proteobacteria) with polar flagella and display a corkscrew-like motion. H. pylori has been isolated from diverse populations throughout the world. The prevalence of infection with this organism increases with age: by age 60 years, half the population has serologic evidence of infection. Twin studies have shown genetic influences in susceptibility to infection with H. pylori. Intrafamilial clustering of H. pylori infection suggests that these bacteria may spread from person to person. Two thirds of those who have been infected with H. pylori show histologic evidence of chronic gastritis. H. pylori is considered to be the pathogen responsible for chronic antral gastritis rather than as a commensal that colonizes injured gastric mucosa because: (1) gastritis develops in healthy persons after ingesting the organism, (2) H. pylori attaches to the epithelium in areas of chronic gastritis and is absent from uninvolved areas of the gastric mucosa, (3) eradicating the infection with bismuth or antibiotics cures the gastritis, (4) antibodies against H. pylori are routinely found in persons with chronic gastritis, and (5) the increasing prevalence of H. pylori infection with age parallels that of chronic gastritis. H. pylori is found only on the epithelial surface and does not invade. Its pathogenicity is related to the cag pathogenicity island in its genome—a horizontally acquired locus of 40 kb that contains 31 genes. This virulence marker is putatively associated with duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. A separate region of the genome contains the gene for vacuolating cytotoxin (vac A), which is also associated with duodenal ulcer disease. Chronic infection with H. pylori also predisposes to the development of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach. |

FIGURE 13-12. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. A. The antrum shows an intense lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate which tends to be heaviest in the superficial portions of the lamina propria. B. The microorganisms appear on silver staining as small, curved rods on the surface of the gastric mucosa.

|

|

Stomach

|

Ménétrier disease (hyperplastic hypersecretory gastropathy) is an uncommon gastric disorder characterized by enlarged rugae. It is often accompanied by a severe loss of plasma proteins (including albumin) from the altered gastric mucosa. A childhood form is due to cytomegalovirus infection; an adult form is attributed to overexpression of transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α).

|

FIGURE 13-13. Ménétrier disease. The folds of the stomach are increased in height and thickness, forming a convoluted surface that has been likened to those of the cerebrum.

|

|

|

Gastric ulcers (Fig. 13-16) are usually single and smaller than 2 cm in diameter. Ulcers on the lesser curvature are commonly associated with chronic gastritis, whereas those on the greater curvature are often related to NSAIDs. Edges tend to be sharply punched out, with overhanging margins. Deeply penetrating ulcers produce a serosal exudate that may cause adherence of the stomach to surrounding structures. Scarring of ulcers in the prepyloric region may be severe enough to produce pyloric stenosis. Grossly, chronic peptic ulcers may closely resemble ulcerated gastric carcinomas. Thus, the endoscopist must take multiple biopsies from the edges and bed of any gastric ulcer.

|

FIGURE 13-16. Gastric ulcer. There is a characteristic sharp demarcation from the surrounding mucosa, with radiating gastric folds. The base of the ulcer is gray owing to fibrin deposition.

|

|

Duodenum

|

Duodenal ulcers (Fig. 13-17) are ordinarily on the anterior or posterior wall of the first part of the duodenum, close to the pylorus. Lesions are usually solitary, but it is not uncommon to find paired ulcers on both walls, so-called kissing ulcers.

|

FIGURE 13-17. Duodenal ulcer. There are two sharply demarcated duodenal ulcers surrounded by inflamed duodenal mucosa. The gastroduodenal junction is in the mid portion of the photograph.

|

|

Stomach

|

Microscopically, gastric and duodenal ulcers are similar (Fig. 13-18). From the lumen outward, the following are noted: (1) a superficial zone of fibrinopurulent exudate; (2) necrotic tissue; (3) granulation tissue; and (4) fibrotic tissue at the base of the ulcer, which exhibits variable degrees of chronic inflammation. Ulceration may penetrate the muscle layers, causing them to be interrupted by scar tissue after healing. Blood vessels on the margins of the ulcer are often thrombosed. The mucosa at the margins tends to be hyperplastic, and with healing grows over the ulcerated area as a single layer of epithelium. Duodenal ulcers are usually accompanied by peptic duodenitis, with Brunner gland hyperplasia and gastric mucin cell metaplasia.

|

FIGURE 13-18. Gastric ulcer. A. There is full thickness replacement of the gastric muscularis with connective tissue. B. Photomicrograph of a peptic ulcer with superficial exudate over necrosis, granulation tissue and fibrosis.

|

|

Stomach

|

Stromal Tumors in the Stomach Tend to Be NonAggressive

Nearly all gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are derived from the pacemaker cells of Cajal and include the vast majority of mesenchymal derived stromal tumors of the entire gastrointestinal tract. The pacemaker cells and the tumor cells express the c-kit oncogene (CD117) that encodes a tyrosine kinase that regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis. The criteria to evaluate aggressive behavior in all GISTs include size, necrosis, and the number of mitotic figures. Interestingly, many of gastric GISTs, independently of size, tend to behave in a nonaggressive fashion, as opposed to small and large bowel tumors, which more commonly behave in a malignant manner. Gastric GISTs are usually submucosal (Fig. 13-19) and covered by intact mucosa or, when they project externally, by peritoneum. The cut surface is whorled. Microscopically, the tumors are variably cellular, and are composed of spindle-shaped cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles embedded in a collagenous stroma. The cells are disposed in whorls and interlacing bundles. Bizarre and giant nuclei do not necessarily suggest malignancy. GISTs P.569 can also appear more epithelioid, with cells that are polygonal and have eosinophilic cytoplasm. With few exceptions, GISTs are considered tumors of low malignant potential. Treatment of GISTs consists mainly of surgical resection. |

FIGURE 13-19. A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach. The resected tumor is submucosal and covered by a focally ulcerated mucosa. B. Microscopic examination of the tumor shows spindle cells with vacuolated cytoplasms.

|

|

Stomach

|

Ulcerating adenocarcinomas comprise another third of all gastric cancers. They have shallow ulcers of variable size (Fig. 13-20). Surrounding tissues are firm, raised and nodular. Characteristically, the lateral margins of the ulcer are irregular and the base is ragged. This appearance stands in contrast to that of the usual benign peptic ulcer, which exhibits punched-out margins and a smooth base. Despite these differences, radiologic differentiation of ulcerating cancer from peptic ulcer is occasionally difficult.

|

FIGURE 13-20. Ulcerating gastric carcinoma. In contrast to the benign peptic ulcer the edges of this lesion are raised and firm. Note the atrophy of the surrounding mucosa.

|

|

Stomach

|

Diffuse or infiltrating adenocarcinoma accounts for one tenth of all stomach cancers. No true tumor mass is seen; instead, the wall of the stomach is thickened and firm (Fig. 13-21). If the entire stomach is involved, it is called a linitis plastica tumor. In the diffuse type of gastric carcinoma, invading tumor cells induce extensive fibrosis in the submucosa and muscularis. Thus, the wall is stiff and may be more than 2 cm thick.

|

FIGURE 13-21. Infiltrating gastric carcinoma (linitis plastica). Cross section of gastric wall thickened by tumor and fibrosis.

|

|

Stomach

|

Tumor cells may contain cytoplasmic mucin that displaces the nucleus to the periphery of the cell, resulting in the so-called signet ring cell (Fig. 13-22).

|

FIGURE 13-22. Infiltrating gastric carcinoma. A. Numerous signet ring cells (arrows) infiltrate the lamina propria between intact crypts. B. Mucin stains highlight the presence of mucin within the neoplastic cells.

|

|

Stomach

|

Early gastric cancer is defined as a tumor limited to the mucosa or submucosa (Fig. 13-23). The older term, superficial spreading carcinoma, is synonymous with early gastric cancer. In Japan, early gastric cancer accounts for one third of all stomach cancers, but only 5% in the United States and Europe.

Early gastric cancer is strictly a pathologic diagnosis based on depth of invasion; the term does not refer to the duration of the disease, its size, presence of symptoms, absence of metastases or curability. Up to 20% of early gastric cancers have already metastasized to lymph nodes at the time of detection. |

FIGURE 13-23. Early gastric cancer. Gastric adenocarcinoma showing malignant glands infiltrating into the submucosa.

|

|

Stomach

|

Primary lymphoma of the stomach accounts for about 5% of all gastric malignancies, and 20% of all extranodal lymphomas. Clinically and radiologically, it mimics gastric adenocarcinoma. Presenting symptoms, as with gastric adenocarcinoma, are usually weight loss, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain. The age at diagnosis is usually 40 to 65 years and there is no sex predominance. The tumors grossly resemble carcinomas, because they may be polypoid, ulcerating or diffuse (Fig. 13-25). Most gastric lymphomas are low-grade B-cell neoplasms of the MALToma type and arise in the setting of chronic H. pylori gastritis with lymphoid hyperplasia. Some of actually regress after eradication of the H. pylori infection. Other histopathologic varieties are similar to those in primary nodal lymphomas.

|

FIGURE 13-25. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. A. There is loss of detail within the gastric mucosa as a MALT lymphoma infiltrates the mucosa over a large surface area, although a discrete mass was not formed. B. Microscopically, there is a monotonous population of lymphoid cells expands the lamina propria.

|

|

Stomach

|

Bezoars are foreign bodies made of food or hair altered by the digestive process.

PHYTOBEZOAR: These vegetable concretions are unusual, except in persons who eat many persimmons or swallow unchewed bubble gum. Phytobezoars are usually seen in persons with delayed gastric emptying, as in the peripheral neuropathy of diabetes or gastric cancer, and in people undergoing therapy with anticholinergic agents. Recently, phytobezoars have been found principally in patients who display delayed gastric emptying and hypochlorhydria after partial gastrectomy, particularly when surgery includes vagotomy. Plant bezoars contain vegetable or fruit fibers. Most patients with persimmon bezoars have bleeding from an associated gastric ulcer. The preferred treatment of phytobezoars is chemical attack with cellulase; in some cases, manual disruption by endoscopic techniques, including jets of water, has been successful. However, enzymatic therapy is usually not effective for persimmon bezoars, and surgery is required. TRICHOBEZOAR: This mass is a hairball within a gelatinous matrix, usually seen in long-haired girls or young women who eat their own hair as a nervous habit. Trichobezoars may grow by accretion to form a complete cast of the stomach, potentially reaching 3 kg |

FIGURE 13-26. Trichobezoar (hairball). A mass of hair in a gelatinous matrix forms a cast of the stomach.

|

|

|

Meckel diverticulum, caused by persistence of the vitelline duct, is an outpouching of the gut on the antimesenteric ileal border, 60 to 100 cm from the ileocecal valve in adults. It is the most common and the most clinically significant congenital anomaly of the small intestine (Fig. 13-28). Two thirds of patients are younger than 2 years.

Meckel diverticulum is a true diverticulum. It possesses all the coats of normal intestine; the mucosa is similar to that of the adjoining ileum. Most Meckel diverticula are asymptomatic and discovered only as incidental findings at laparotomy for other causes or at autopsy. Of the minority that becomes symptomatic, about half contain ectopic gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, biliary, or colonic tissue. |

FIGURE 13-28. Meckel diverticulum. A contrast radiograph of the small intestine shows a barium-filled diverticulum of the ileum (arrow).

|

|

|

ARTERIAL OCCLUSION: Sudden occlusion of a large artery by thrombosis or embolization leads to small bowel infarction before collateral circulation comes into play. Depending on the size of the artery, infarction may be segmental or may lead to gangrene of virtually the entire small bowel (Fig. 13-29). Occlusive intestinal infarction is most often caused by embolic or thrombotic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery. A lesser number are the result of vasculitis, which often involves small arteries. In addition to intrinsic vascular lesions, volvulus, intussusception and incarceration of the intestine in a hernial sac may all lead to arterial as well as venous occlusion.

|

FIGURE 13-29. Infarct of the small bowel. This infant died after an episode of intense abdominal pain and shock. Autopsy demonstrated volvulus of the small bowel that had occluded the superior mesenteric artery. The entire small bowel is dilated, gangrenous, and hemorrhagic.

|

|

small intestine

|

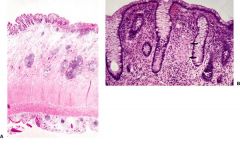

GENETIC FACTORS: Celiac sprue is caused by an interplay of complex genetic factors plus an abnormal immune response to ingested cereal antigens. Overt and latent celiac disease run in families. Concordance for celiac disease in first-degree relatives ranges between 8% and 18% and reaches 70% in monozygotic twins. About 90% of patients with celiac disease carry the histocompatibility antigen human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B8 and a comparable frequency has been reported for HLA DR8 and DQ2.

IMMUNOLOGIC FACTORS: The intestinal lesion in celiac disease is characterized by damage to the epithelial cells and a marked increase in the number of T lymphocytes within the epithelium and of plasma cells in the lamina propria. Gliadin challenge of persons with treated celiac sprue stimulates local immunoglobulin synthesis. ASSOCIATION WITH DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS: Celiac disease is occasionally associated with dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), a vesicular skin disease that typically affects extensor surfaces and exposed parts of the body. In DH, subepidermal neutrophil infiltration leads to local edema and blister formation. Basement membrane IgA deposits are detected. Almost all patients with DH have a small bowel mucosal lesion similar to that of celiac disease, although only 10% have overt malabsorption. Treatment with a strict gluten-free diet leads to improvement in both gastrointestinal symptoms and skin lesions. The histocompatibility antigen HLA-B8 is much more frequent in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis than in normal persons. Malabsorption in celiac disease probably results from multiple factors, including reduced intestinal mucosa surface area (due to blunting of villi and microvilli) and impaired intracellular metabolism within damaged epithelial cells. A probable aggravating factor is secondary disaccharidase deficiency, related to damage to microvilli. A hypothetical mechanism for the pathogenesis of celiac disease is presented in Figure 13-31. |

FIGURE 13-32. Celiac disease. A. Normal proximal small intestine shows tall slender villi with crypts present at the base. B. Normal surface epithelium shows an occasional intraepithelial lymphocyte as well as an intact brush border. C. A mucosal biopsy from a patient with advanced celiac disease shows complete loss of the villi with infiltration of the lamina propria by lymphocytes and plasma cells. The crypts are increased in height. D. At higher power the surface epithelium is severely damaged with large numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes and loss of the brush border.

|

|

jejunum

|

Whipple disease typically shows infiltration of the small bowel mucosa by macrophages packed with small, rod-shaped bacilli. The causative organism is one of the actinomycetes, Tropheryma whippelii. Interestingly, T. whippelii is distantly related to mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, both of which have been associated with illnesses resembling Whipple disease. The results of several studies suggest that host susceptibility factors, possibly defective T-lymphocyte function, may be important in predisposing to the disease. Macrophages from patients with Whipple disease exhibit decreased ability to degrade intracellular microorganisms. Circulating cells expressing CD11b, a cell-adhesion and complement-receptor molecule on macrophages, are reduced. CD11b is involved in activating macrophages to kill intracellular pathogens. Dramatic clinical remissions occur with antibiotic therapy.

The bowel wall is thickened and edematous, and mesenteric lymph nodes are usually enlarged. Villi are flat and thickened villi, and the lamina propria is extensively infiltrated with large foamy macrophages (Fig. 13-33A) whose cytoplasm is filled with large glycoprotein granules that stain strongly with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) (see Fig. 13-33B). The other normal cellular components of the lamina propria (i.e., plasma cells and lymphocytes) are depleted. The lymphatic vessels in the mucosa and submucosa are dilated and large lipid droplets abound within lymphatics and in extracellular spaces, a finding that suggests lymphatic obstruction. In contrast to the striking distortion of the villous architecture, epithelial cells show only patchy abnormalities, including attenuation of microvilli and accumulation of lipid droplets within the cytoplasm. Electron-microscopic examination reveals numerous small bacilli within macrophages and free in the lamina propria (see Fig. 13-33C). The PAS-positive granules seen by light microscopy correspond to lysosomes engorged with bacilli in various stages of degeneration. Many bacilli cluster immediately beneath the epithelial basement membrane. Mesenteric lymph nodes draining affected segments of small bowel reveal similar microscopic changes. A characteristic infiltration by macrophages containing bacilli may also be found in most other organs. Heart lesions may include valvular vegetations which contain bacilli-laden macrophages, sometimes with superimposed streptococcal endocarditis. Treatment of Whipple disease is with appropriate antibiotics. |

FIGURE 13-33. Whipple disease. A. A photomicrograph of a section of jejunal mucosa shows distortion of the villi. The lamina propria is packed with large, pale-staining macrophages. Dilated mucosal lymphatics are prominent. B. A periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction shows numerous macrophages filled with cytoplasmic granular material. C. An electron micrograph shows small bacilli in a macrophage.

|

|

small intestine

|

INTUSSUSCEPTION: In this form of intraluminal small bowel obstruction a segment of bowel (intussusceptum) protrudes distally into a surrounding outer portion (intussuscipiens) (Fig. 13-34). Intussesception usually occurs in infants or young children, in whom it occurs without a known cause. In adults, the leading point of an intussusception is usually a lesion in the bowel wall, such as Meckel diverticulum or a tumor. Once the leading point is entrapped in the intussuscipiens, peristalsis drives the intussusceptum forward. In addition to acute intestinal obstruction, intussusception compresses the blood supply to the intussusceptum, which may become infarcted. If the obstruction is not relieved spontaneously, treatment requires surgery.

|

FIGURE 13-34. Intussusception. A cross section through the area of the obstruction shows “telescoped” small intestine surrounded by dilated small intestine.

|

|

intestinal epithelium

|

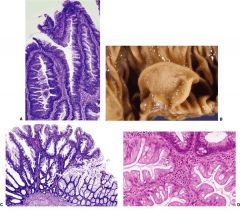

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant hereditary disorder characterized by intestinal hamartomatous polyps and mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation, which is particularly evident on the face, buccal mucosa, hands, feet, and perianal and genital areas. Except for the buccal pigmentation, the frecklelike macular lesions usually fade at puberty. The polyps occur mostly in the proximal small intestine but are sometimes seen in the stomach and the colon. Patients usually have symptoms of obstruction or intussusception; in as many as one fourth of cases, however, the diagnosis is suggested by pigmentation in an otherwise asymptomatic person.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is associated with inactivating mutations of a gene (LKB1) on chromosome 19p that encodes a protein kinase. Carriers of the defective gene are also at increased risk for cancers of the breast, pancreas, testis, and ovary. P.587 Peutz-Jeghers polyps are hamartomas, with branching networks of smooth muscle fibers continuous with the muscularis mucosae supports the glandular epithelium of the polyp (Fig. 13-35). Peutz-Jeghers polyps are generally considered benign, but 3% of patients develop adenocarcinoma, although not necessarily in the hamartomatous polyps. |

FIGURE 13-35. Peutz-Jegher polyps. The intestinal epithelium has peculiar shapes but unremarkable nuclear and cytoplasmic features. Arborizing large bundles of smooth muscle are characteristic.

|

|

distal ileum

|

The term carcinoid tumor has been largely replaced by the term neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). These tumors are all considered malignant, but usually with low metastatic potential. The gut is the most common site for NETs (the bronchus is the next most common site). The site of origin is a major determinant of behavior. Other important considerations include size, depth of invasion, hormonal responsiveness, and presence or absence of function.

The appendix is the most common gastrointestinal site of origin, followed by the rectum. Tumors of these sites are usually small and rarely aggressive. The next most common site is ileum, where they are often multiple, and more aggressive. NETs account for about 20% of all small intestinal malignancies. They are also seen in association with the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes, usually type I. Macroscopically, small carcinoid tumors present as submucosal nodules covered by intact mucosa. Large carcinoids may grow in a polypoid, intramural, or annular pattern (Fig. 13-37A) and often undergo secondary ulceration. The cut surface is firm and white to yellow. As they enlarge, carcinoid tumors invade the muscular coat and penetrate the serosa, often causing a conspicuous desmoplastic reaction. This fibrosis is responsible for peritoneal adhesions and kinking of the bowel, which may lead to intestinal obstruction. Microscopically, these neoplasms appear as nests, cords and rosettes of uniform small, round cells (see Fig. 13-37B). Occasional glandlike structures are also seen. Nuclei are remarkably regular and mitoses are rare. Abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm contains cytoplasmic granules, which by electron microscopy are typically of the neurosecretory type. Goblet cell carcinoids or adenocarcinoid tumors have glandular differentiation. These tumors have a higher rate of aggressive behavior than do typical carcinoids. NETs metastasize first to regional lymph nodes. Subsequently, hematogenous spread produces metastases at distant sites, particularly the liver. |

FIGURE 13-37. Neuroendocrine tumor of small intestine. A. A resected segment of distal ileum shows multiple neuroendocrine tumors (arrows). B. A photomicrograph of the lesion in A demonstrates cords of uniform small, round cells.

|

|

rectosigmoid colon

|

Hirschsprung disease is a disorder in which colon dilation (Fig. 13-38) results from a defect in colorectal innervation: congenital absence of ganglion cells, in most cases in the wall of the rectum (Fig. 13-39). In one fourth of cases, ganglion cells are deficient in moreproximal portions of the colon and in unusual instances, the lesion may extend as far as the small intestine. The incidence of the disorder is estimated to be 1 in 5000 live births, and 80% of patients are male.

The large intestine in Hirschsprung disease has a constricted and spastic segment that is the aganglionic zone. Proximal to this, the bowel is very dilated. The definitive diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease is made on the basis of absence of ganglion cells in a rectal biopsy specimen (see Fig. 13-39B). There is also a striking increase in nonmyelinated cholinergic nerve fibers in the submucosa and between the muscle coats (neural hyperplasia). The absence of ganglion cells leads to accumulation of acetylcholine and acetylcholinesterase. Histochemical demonstration of this enzyme, which is not visualized in normal rectal mucosa, enhances the reliability of a diagnosis based on rectal biopsy. Interestingly, like achalasia, which is caused by destruction of esophageal ganglion cells, Chagas disease may cause aganglionic megacolon. |

FIGURE 13-38. Hirschsprung disease. A contrast radiograph shows marked dilation of the rectosigmoid colon proximal to the narrowed rectum.

|

|

rectum

|

Hirschsprung disease is the most common cause of congenital intestinal obstruction. The clinical signs are delayed passage of meconium by a newborn and development of vomiting in the first few days of life. In some cases, complete intestinal obstruction requires immediate surgical relief. In children who have short rectal segments lacking ganglion cells and who have only partial obstruction, constipation, abdominal distention, and recurrent fecal impactions are characteristic.

The most serious complication of congenital megacolon is an enterocolitis, in which necrosis and ulceration affect the dilated proximal segment of the colon and may extend into the small intestine. The treatment for Hirschsprung disease is surgical removal of the aganglionic segment and reconstruction. |

FIGURE 13-39. Hirschsprung disease. A. A photomicrograph of ganglion cells in the wall of the rectum (arrows). B. A rectal biopsy specimen from a patient with Hirschsprung disease shows a nonmyelinated nerve in the mesenteric plexus and an absence of ganglion cells.

|

|

|

Macroscopically, the colon, particularly the rectosigmoid region, shows raised yellowish plaques up to 2 cm in diameter that adhere to the underlying mucosa (Fig. 13-40). The intervening mucosa appears congested and edematous but is not ulcerated. In severe cases, plaques coalesce into extensive pseudomembranes. Necrosis of the superficial epithelium is believed to be the initial pathologic event. Subsequently, crypts become disrupted and expanded by mucin and neutrophils. The pseudomembrane consists of the debris of necrotic epithelial cells, mucus, fibrin, and neutrophils. In milder cases, well formed pseudomembranes may be absent, and the pathology is more subtle, with focal damage to the surface epithelium.

When both small and large bowel are involved, the condition is referred to as pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Pseudomembranes occur occasionally in other enteric infections, involving Staphylococcus aureus, Candida, invasive bacteria, and verotoxin-producing E. coli. Ischemic bowel disease may also show pseudomembranes. Antibiotic-associated infections with C. difficile are virtually always accompanied by diarrhea, but in most cases, the disorder does not progress to colitis. In patients with pseudomembranous colitis, fever, leukocytosis, and abdominal cramps are superimposed on the diarrhea. Before there were antibiotics, many patients with this form of colitis died within hours or days from ileus and irreversible shock. Today, pseudomembranous colitis, although still serious, is usually controlled with antibiotics and supportive fluid and electrolyte therapy. Milder cases can be confused with an array of diarrheal diseases. |

FIGURE 13-40. Pseudomembranous colitis. A. The colon shows variable involvement ranging from erythema to yellow-green areas of pseudomembrane. B. Microscopically, the pseudomembrane consists of fibrin, mucin and inflammatory cells (largely neutrophils).

|

|

colon

|

Diverticulosis is generally asymptomatic, and 80% of affected persons remain symptom free. Many patients complain of episodic colicky abdominal pain. Both constipation and diarrhea, sometimes alternating, may occur, and flatulence is common. Sudden, painless and severe bleeding from colonic diverticula is a cause of serious lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the elderly, occurring in as many as 5% of persons with diverticulosis. Chronic blood loss may lead to anemia.

Diverticulitis presumably results from irritation caused by retained fecal material. In 10% to 20% of patients with diverticulosis, diverticulitis supervenes at some point. |

FIGURE 13-41. Diverticulosis of the colon. A. The colon was inflated with formalin. The mouths of numerous diverticula are seen between the taenia (arrows). There is a blood clot seen protruding from the mouth of one of the diverticula (arrowhead). This was the source of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. B. Sections show mucosa including mucularis mucosae which has herniated through a defect in the bowel wall producing a diverticulum.

|

|

terminal ileum

|

Two major characteristics of Crohn disease differentiate it from other gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases. First, the inflammation usually involves all layers of the bowel wall and is, therefore, referred to as transmural inflammatory disease. Second, the involvement of the intestine is discontinuous; that is, segments of inflamed tissue are separated by apparently normal intestine.

It is convenient to classify Crohn disease into four broad macroscopic patterns, although many patients do not fit any one of them precisely. The disease involves (1) mainly the ileum and cecum in about 50% of cases, (2) only the small intestine in 15%, (3) only the colon in 20%, and (4) mainly the anorectal region in 15%. Disease of the ileum and cecum is more frequent in young persons; colitis is common in older patients. Crohn disease is occasionally seen in the duodenum and stomach as focal acute inflammation with or without granulomas. More rarely, it occurs in the esophagus and oral cavity, almost always in association with small intestinal disease. In women with anorectal Crohn disease, the inflammation may spread to involve the external genitalia. |

FIGURE 13-42. Crohn disease. A. The terminal ileum shows striking thickening of the wall of the distal portion with distortion of ileocecal valve. A longitudinal ulcer is present (arrows). B. Another longitudinal ulcer is seen in this segment of ileum. The large rounded areas of edematous damaged mucosa give a “cobblestone” appearance to the involved mucosa. A portion of the mucosa to the lower right is uninvolved.

|

|

colon

|

The clinical manifestations and natural history of Crohn disease are highly variable and relate to the anatomical sites involved by the disease. The most frequent symptoms are abdominal pain and diarrhea, which are seen in over 75% of patients, and recurrent fever, evident in 50%. When disease mainly involves the ileum and cecum, sudden onset may mimic appendicitis, and the diagnosis is occasionally first made at the time of abdominal surgery. If the disease predominantly involves the ileum, the major clinical features are right lower quadrant pain, intermittent diarrhea and fever, and frequently a tender mass in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. When the small intestine is diffusely involved, malabsorption and malnutrition may be major features. Lipid malabsorption may also result from interruption of enterohepatic cycle of bile salts because of ileal disease. Crohn disease of the colon leads to diarrhea and sometimes colonic bleeding. In a few patients, the major site of involvement is the anorectal region and recurrent anorectal fistulas are the presenting sign.

Intestinal obstruction and fistulas are the most common intestinal complications of Crohn disease. Occasionally, free perforation of the bowel occurs. Small bowel cancer is at least threefold more common in patients with Crohn disease, and the disease also predisposes to colorectal cancer. When Crohn disease begins in childhood, it may lead to retardation of growth and physical development. Systemic complications also include liver disease (sclerosing cholangitis), cholelithiasis, renal oxalate stones, and amyloidosis. The most frequent extraintestinal inflammatory features are in the eye (episcleritis or uveitis), medium-sized joints (arthritis), and skin (erythema nodosum). No cure is available. Several medications suppress the inflammatory reaction, including corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, metronidazole, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, and anti-TNF antibodies. Surgical resection of obstructed areas or of severely involved portions of intestine and drainage of abscesses caused by fistulas are required in some cases. Preanastomotic or prestomal recurrences after construction of an enterostomy is a hallmark of Crohn disease, a feature that makes clinical management difficult. The need for repeated resections can lead to short-bowel syndrome in some patients. Microscopically, Crohn disease appears as a chronic inflammatory process. During early phases of the disease, the inflammation may be confined to the mucosa and submucosa. Small, superficial mucosal ulcerations (aphthous ulcers) are seen, together with mucosal and submucosal edema and an increase in the number of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. Destruction of mucosal architecture, with regenerative changes in crypts and villous distortion, are frequent. Pyloric metaplasia and Paneth cell hyperplasia is common in the small intestine and colorectum. Later, long, deep, fissurelike ulcers are seen, and vascular hyalinization and fibrosis become apparent. The microscopic hallmark of Crohn disease is transmural nodular lymphoid aggregates, accompanied by proliferative changes of the muscularis mucosae and nerves of submucosal and myenteric plexuses (Fig. 13-43). Discrete, noncaseating granulomas, mostly in the submucosa, may be present. These granulomas are like those of sarcoidosis and consist of focal aggregates of epithelioid cells, vaguely limited by a rim of lymphocytes. Multinucleated giant cells may be present. The centers of the granulomas usually display hyaline material and only very rarely necrosis. |

FIGURE 13-43. Crohn disease. A. The colon involved with Crohn disease shows an area of mucosal ulceration, an expanded submucosa with lymphoid aggregates, and numerous lymphoid aggregates in the subserosal tissues immediately adjacent to the muscularis externa. B. This mucosal biopsy in Crohn disease shows a small epithelioid granuloma (arrows) between two intact crypts.

|

|

colon

|

Three major pathologic features characterize ulcerative colitis and help to differentiate it from other inflammatory conditions:

Ulcerative colitis is a diffuse disease. It usually extends from the most distal part of the rectum for a variable distance proximally (Fig. 13-45). When it involves the rectum alone, it is called ulcerative proctitis. When the process extends toward the splenic flexure, the terms proctosigmoiditis and left-sided colitis are used. Sparing of the rectum or involvement of the right side of the colon alone is rare and suggests the possibility of another disorder, such as Crohn disease. Inflammation in ulcerative colitis is generally limited to the colon and rectum. It rarely involves the small intestine, stomach, or esophagus. If the cecum is affected, the disease ends at the ileocecal valve, although minor inflammation of the adjacent ileum is sometimes noted (backwash ileitis). Ulcerative colitis is essentially a mucosal disease. Deeper layers are uncommonly involved, mainly in fulminant cases, usually in association with toxic megacolon. |

FIGURE 13-45. Ulcerative colitis. Prominent erythema and ulceration of the colon begin in the ascending colon and are most severe in the rectosigmoid area.

|

|

colon

|

The clinical course and manifestations are very variable. Most patients (70%) have intermittent attacks, with partial or complete remission between attacks. A small number (<10%) have a very long remission (several years) after their first attack. The remaining 20% have continuous symptoms without remission.

MILD COLITIS: Half of patients with ulcerative colitis have mild disease. Their major symptom is rectal bleeding, sometimes accompanied by tenesmus (rectal pressure and discomfort). The disease in these patients is usually limited to the rectum but may extend to the distal sigmoid colon. Extraintestinal complications are uncommon, and in most patients in this category, disease remains mild throughout their lives. MODERATE COLITIS: About 40% of patients have moderate ulcerative colitis. They usually have recurrent episodes of loose bloody stools, crampy abdominal pain, and frequently low-grade fever, lasting days or weeks. Moderate anemia is a common result of chronic fecal blood loss. SEVERE COLITIS: About 10% of patients have severe or fulminant ulcerative colitis, sometimes from its onset but often during a flare of activity. They may have more than 6 and sometimes more than 20, bloody bowel movements daily, often with fever and other systemic manifestations. Blood and fluid loss rapidly leads to anemia, dehydration, and electrolyte depletion. Massive hemorrhage may be life-threatening. A particularly dangerous complication is toxic megacolon, which is characterized by extreme dilation of the colon. Patients with this condition are at high risk for perforation of the colon. Fulminant ulcerative colitis is a medical emergency requiring immediate, intensive medical therapy, and, in some cases, prompt colectomy. About 15% of patients with fulminant ulcerative colitis die of the disease. The medical treatment of ulcerative colitis depends on the sites involved and the severity of the inflammation. The 5-aminosalicylate–based compounds are the mainstays of treatment for patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive and immunoregulatory agents (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) are used in patients who have severe and refractory disease. |

FIGURE 13-46. Ulcerative colitis. A. A full thickness section of colon resected for ulcerative colitis shows inflammation affecting the mucosa with sparing of the submucosa and muscularis propria. B. Sections of a mucosal biopsy from a patient with active ulcerative colitis shows expansion of the lamina propria and several crypt abscesses (arrows). C. Chronic ulcerative colitis shows significant crypt distortion and atrophy.

|

|

colon

|

PROGRESSIVE COLITIS: As the disease continues, mucosal folds are lost (atrophy). Lateral extension and coalescence of crypt abscesses can undermine the mucosa, leaving areas of ulceration adjacent to hanging fragments of mucosa. Such mucosal excrescences are termed inflammatory polyps (Fig. 13-47). Tissue destruction is accompanied by manifestations of tissue repair. Granulation tissue develops in denuded areas. Importantly, the strictures characteristic of Crohn disease are absent. Microscopically, colorectal crypts may appear tortuous, branched, and shortened in the late stages and the mucosa may be diffusely atrophic.

|

FIGURE 13-47. Inflammatory polyps of the colon in ulcerative colitis. Nodules of regenerative mucosa and inflammation surrounded by denuded areas provide a diffuse polypoid appearance of the mucosa.

|

|

colon

|

Colorectal epithelial dysplasia is a neoplastic epithelial proliferation and precursor to colorectal carcinoma in patients with long-term ulcerative colitis (Fig. 13-49). The histopathologic criteria include (1) alteration of mucosal architecture, (2) epithelial abnormalities (hypercellularity and stratification of nuclei), and (3) epithelial dysplasia (variation in the size, shape, and staining qualities of nuclei). Dysplasia is divided into low-grade and high-grade dysplasia. High-grade epithelial dysplasia reflects a high risk for the development of colorectal cancer and when identified in a biopsy, it is a strong indication for colectomy. Routine surveillance by colonoscopic biopsy of all patients with ulcerative colitis is, therefore, recommended.

|

FIGURE 13-49. Dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. The colonic mucosa shows the chronic changes of ulcerative colitis (see Fig. 13-46). The crypts to the left are dysplastic.

|

|

colon

|

Collagenous colitis is an inflammatory disorder of the colon characterized clinically by chronic watery diarrhea and pathologically by a thickened subepithelial collagen band. The disorder mainly afflicts middle-aged and elderly women.

The colonic mucosa appears grossly normal. The histopathologic diagnosis of collagenous colitis is made by demonstrating a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the mucosa and a band of collagen immediately beneath the surface epithelium that measures up to 80 µm (Fig. 13-50). The surface epithelium shows flattened or cuboidal cells and even separation of epithelial cells from underlying structures. Intraepithelial lymphocytes are common. The lamina propria contains increased numbers of chronic inflammatory cells and neutrophils are also found in some patients. Lymphocytic colitis also features prominent infiltration of the damaged colonic epithelium by lymphocytes but lacks the collagen table and has an equal sex distribution. Patients with lymphocytic colitis have more than 10 lymphocytes for every 100 epithelial cells. |

FIGURE 13-50. Collagenous colitis. A trichrome stainhighlights the characteristic thickening of the collagen table (blue, note arrows) with entrapment of capillaries. The intercryptal surface epithelium is flattened and contains an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes.

|

|

|

Some patients with symptoms and complications of bowel infarction require immediate surgical intervention. However, in most patients, the acute signs stabilize, and radiographic examination shows only the pattern associated with intramural hemorrhage and edema. On endoscopy, multiple ulcers, hemorrhagic nodular lesions, or a pseudomembrane is seen. Biopsy reveals ischemic necrosis of the bowel: mucosal ulceration, crypt abscesses, edema, and hemorrhage (Figure 13-51). Such patients may recover completely or may develop a colonic stricture, in which case, surgical removal of the obstructed segment is necessary. Segments of ischemic stricture show variable mucosal ulceration and inflammation, as well as submucosal widening by granulation tissue and fibrosis. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages may be noted, and patchy fibrosis of the muscular coats also may be present.

Ischemic disease of the rectosigmoid area typically manifests as abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and a change in bowel habits. On clinical grounds alone, ischemic colitis often cannot be distinguished from some forms of infective colitis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn colitis. Prognosis and treatment depend on the primary cause and extent of involvement. The goal is to improve blood supply to the colon by treating patients' overall cardiovascular status. Acute interruption of blood supply to the colon can be fatal in neonates and elderly persons. |

FIGURE 13-51. Ischemic colitis. A mucosal biopsy shows coagulative necrosis with “ghostly” outlines the preexisting crypts. Only a small portion of the base of several crypts remain.

|

|

colon

|

TUBULAR ADENOMAS: These constitute two thirds of the benign large bowel adenomas. Tubular adenomas are typically smooth-surfaced lesions, usually less than 2 cm in diameter, which often have a stalk (Fig. 13-52). Some tubular adenomas, particularly the smaller ones, are sessile.

Microscopically, tubular adenoma has closely packed epithelial tubules, which may be uniform or irregular and excessively branched (see Fig. 13-52C). Tubules are embedded in a fibrovascular stroma similar to the normal lamina propria. |

FIGURE 13-52. Tubular adenoma of the colon. A. The adenoma shows a characteristic stalk and bosselated surface. B. The bisected adenoma shows the stalk covered by the adenomatous epithelium. The ashen white color is cautery at the polypectomy resection margin from the polypectomy. C. Microscopically, the adenoma shows a repetitive pattern that is largely tubular. The stalk, which is in continuity with the submucosa of the colon, is not involved and is lined by normal colonic epithelium.

|

|

colon?

|

Although most tubular adenomas show little epithelial dysplasia, one fifth (particularly larger tumors) may have dysplastic features, which vary from mild nuclear pleomorphism to frank invasive carcinoma (Fig. 13-53).

|

FIGURE 13-53. Adenocarcinoma arising in a pedunculated adenomatous polyp. A. Both low-grade dysplasia and high-grade dysplasia are present. The latter is characterized by a cribriform pattern and increased nuclear pleomorphism (arrows). B. Trichrome stain showing tumor invading the stalk (blue). Since there was a margin of resection of over 1 mm, polypectomy was sufficient therapy.

|

|

colon

|

VILLOUS ADENOMAS: These polyps constitute one tenth of colonic adenomas and are found predominantly in the rectosigmoid region. They are typically large, broad-based, elevated lesions with a shaggy, cauliflower-like surface (Fig. 13-54A), but they can be small and pedunculated. Most are over 2 cm in diameter. On occasion, they reach 10 to 15 cm across. Microscopically, villous adenomas are composed of thin, tall, fingerlike processes that superficially resemble the villi of the small intestine. They are lined externally by neoplastic epithelial cells and are supported by a core of fibrovascular connective tissue corresponding to the normal lamina propria (Fig. 13-54B).

The histopathology of dysplasia in villous adenomas is comparable to that in tubular adenomas. However, villous adenomas contain foci of carcinoma more often than tubular adenomas. In polyps less than 1 cm across, the risk is 10 times higher than that for comparably sized tubular adenomas. Of greater importance is the fact that 50% of villous adenomas larger than 2 cm harbor invasive carcinoma. Given that most villous adenomas measure more than 2 cm in greatest dimension, more than one third of all resected villous adenomas contain invasive cancer. |

FIGURE 13-54. Villous adenoma of the colon. A. The colon contains a large, broad-based, elevated lesion that has a cauliflower-like surface. A firm area near the center of the lesion proved on histologic examination to be an adenocarcinoma. B. Microscopic examination shows fingerlike processes with fibrovascular cores line by hyperchromatic nuclei.

|

|

colon?

|

Hyperplastic polyps are believed to arise due to a defect in proliferation and maturation of normal mucosal epithelium. In a hyperplastic polyp, proliferation occurs at the base of the crypt, and upward migration of the cells is slowed. Thus, epithelial cells differentiate and acquire absorptive characteristics lower in the crypts. Moreover, cells persist at the surface longer do than normal cells.

Pathology Hyperplastic polyps are small, sessile, raised mucosal nodules, up to 0.5 cm in diameter but occasionally larger. They are almost always multiple and have even been mistaken for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Histologically, the crypts of hyperplastic polyps are elongated and may show cystic dilation (Fig. 13-56). The epithelium contains goblet cells and absorptive cells, with no dysplasia. The surface cells are elongated giving a tufted appearance; this accounts for the serrated contour of the glands near the surface. |

FIGURE 13-56. Hyperplastic polyp. A. This hyperplastic polyp is small, sessile and pale. There are smaller adjacent hyperplastic polyps. B. Microscopically, there is a “sawtooth” appearance to the surface.

|

|

colon

|

There is debate over current nomenclature of these variants. One form has a serrated configuration like that of hyperplastic polyps but with nuclear features of adenomas, and is termed serrated adenoma (Fig. 13-57A). Another type is called sessile serrated adenoma, and resembles classic hyperplastic polyps, but does not show adenomatous features, and often appear as a large deformed mucosal fold (Fig. 13-57B and C). Yet a third variant exhibits juxtaposed areas of hyperplastic polyp and adenoma, referred to as mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps (Fig. 13-57D). Unlike classic hyperplastic polyps, patients with these variants have an increased risk for the development of carcinoma. These lesions have a high incidence of microsatellite instability. The carinomas that arise from them tend to be bulky, mucinous, and right-sided.

|

FIGURE 13-57. Variants of hyperplastic polyps. A. Serrated adenoma. The epithelium shows contours typical of hyperplastic polyp with adenomatous nuclear features. B. Sessile serrated adenoma. A polypoid lesion appears to be an enlarged flattened fold. C. Microscopically, sessile serrated adenoma features irregular, asymmetric crypts that are often dilated by mucin. D. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyp. Two adenomatous crypts in the upper right contrast with the three hyperplastic crypts.

|

|

colon

|

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) is an Autosomal Dominant Trait that Invariably Leads to Cancer

Also termed adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), FAP accounts for less than 1% of colorectal cancers. It is caused by a mutation of the APC gene on the long arm of chromosome 5 (5q21-22) (see below). Most cases are familial, but 30% to 50% reflect new mutations. FAP is characterized by hundreds to thousands of adenomas carpeting the colorectal mucosa, sometimes throughout its length, but particularly in the rectosigmoid area (Fig. 13-58). The adenomas are mostly of the tubular variety, although tubulovillous and villous adenomas are also present. Microscopic adenomas, sometimes involving a single crypt, are numerous. A few polyps are usually present by age 10, but the mean age for occurrence of symptoms is 36 years, by which time cancer is often already present. Carcinoma of the colon and rectum is inevitable, the mean age of onset being 40 years. Total colectomy before onset of cancer is curative, but some patients also have tubular adenomas in the small intestine and stomach that have the same malignant potential as those in the colon. Genetic testing for FAP is available, but mutations are found in only 75% of familial cases. Subtypes of FAP include: |

FIGURE 13-58. Familial polyposis. The colon containes thousands of adenomatous polyps with only several exceeding 1 cm in diameter.

|

|

colon

|

juvenile polyps

|

FIGURE 13-59. Juvenile polyp. A. The resected specimen shows a rounded surface which is dark because of hemorrhage and ulceration. The cut surface (left) is cystic. B. Microscopically, the polyp displays cystically dilated glands.

|

|

colon

|

The vast majority of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas (see Fig. 13-61B) that are microscopically similar to their counterparts in other parts of the digestive tract. Some 10% to 15% secrete large quantities of mucin; these are called mucinous adenocarcinomas. The degree of differentiation influences the prognosis; better-differentiated tumors tend to have a more favorable outlook.

|

FIGURE 13-61. Adenocarcinoma of the colon. A. A resected colon shows an ulcerated mass with enlarged, firm, rolled borders. B. Microscopically, this colon adenocarcinoma consists of moderately differentiated glands with a prominent cribriform pattern and frequent central necrosis.

|