![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

47 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

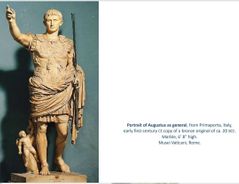

Augustus of Primaporta statue |

The Augustus of Primaporta statue conflates the heroic Greek Doryphoros and the indigenous Etruscan orator types. Augustus’ face is perpetually youthful and handsome, implying an eternally vigorous Rome, as well as a nod to Alexander the Great. Though not a military man, Augustus dons a cuirass featuring the defeated Parthians below the gods: divine favor mandating political victory. The statue further alludes to Augustus’ divine lineage: he is barefoot and accompanied by Cupid, son of Venus – as per Virgil’s Aeneid, Julius Caesar descends from Aeneas, thus Augustus is also a son of Venus. His toga and command baton complete the propagandistic message. This portrait becomes the prototype not only for all subsequent images of Augustus, but for each subsequent emperor wishing to bind themselves to the memory of the first emperor. Portraits of Augustus were often paired with images of his wife and political partner, Livia, first Empress of Rome. Both she and Augustus appeared as steadfast, eternally youthful emblems of Rome’s strength, stability and prosperity. |

|

|

Augustan monuments – A new Golden Age |

Augustus opens marble quarries in Carrara, and begins revamping Rome, styling himself a Roman Perikles, striving to evoke fifth-century Athens. |

|

|

Ara Pacis |

The Ara Pacis is the passion project of Livia. She urged Augustus to create a monument to commemorate the Augustan Peace (Pax Romana), which, as depicted in the relief decorations extends through time and space. The Procession of the Imperial Family, the allegory of Peace, the Sacrifice of Aeneas, as well as a meander and acanthus scrolls appear on the exterior screen of the altar, all evoking Classical Greece. The interior contains symbols of sacrifice. |

|

|

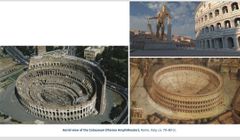

The Flavian Amphitheatre |

The Emperor Nero exploits the devastating fire of 64 CE to create and extravagant Domus Aurea. (following Nero’s (compelled) suicide) he erects the Flavian Amphitheatre, finished in 80 CE. Under his successor, Titus. Nicknamed the Colosseum after the colossal statue of Nero. Faced with sequential orders–Tuscan, Ionic and Corinthian. Socially stratified seating. A velarium shaded visitors. A network of cells, trap doors and platforms are housed beneath the arena. The entire space could be flooded for naumachia. |

|

|

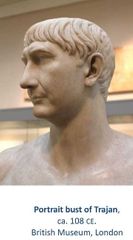

Trajan (98-117 CE) |

Is a general from Spain. Nerva chooses him for his administrative prowess, despite not even being Italian, much less a relative. |

|

|

The Basilica Ulpia |

An enormous clerestoried meeting house lies at the end of the forum, beyond which were two libraries, a posthumous temple to the Divine Trajan and a giant commemorative column with a tomb at its base. |

|

|

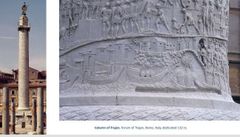

Column of Trajan 112 CE |

A continuous spiral of narrative reliefs depicts stock scenes from Trajan's two successful campaigns against the Dacians, including the Adlocutio, the fording of rivers, the building of fortifications, and pious sacrifices, in addition to battle imagery. Thus Roman organization and technical superiority are shown to be the causes of victory, not the ineptitude of the enemy, who is rendered with dignity. |

|

|

Hadrian (117-138 CE) |

Whom Trajan chooses as his successor, is also from Spain. A Grecophile, his portraiture brings back the beard as symbol of sophistication and scholarship. |

|

|

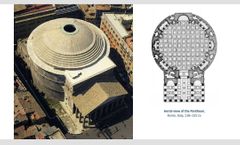

The Pantheon |

Hadrian’s most important building project, this temple dedicated to all the gods replaces an earlier temple built by Agrippa that was destroyed by fire. It features a standard Greek-style gabled portico, originally framed by a colonnaded forum. Behind the porch is a circular rotunda forming a perfect globe: it is a microcosm, enhanced by coffers containing bronze rosettes, meant to evoke the stars. The Dome’s concrete shell gets thinner at top, where it is pierced by an oculus, open to light, air and rain. Hadrian who often held court on the opulent pavement used the space for political theatrics. |

|

|

The High Empire continues (138-192 CE) |

However the run of “Good Emperors” will conclude with Marcus Aurelius’ disastrous decision to elevate his son Commodus to Co-Emperor. |

|

|

The Antonines (138-192 CE) |

Hadrian selects Antoninus Pius as his successor, with the condition that Antonius Pius in turn adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as successors to ensure the continued peaceful transfer of power. |

|

|

Equestrian Statue |

Marcus Aurelius’ gilded-bronze equestrian statue of shows the emperor clement and thoughtful. His massive figure dominates its steed and thus nature itself. Through a mistake of history, the statue becomes the prototype for Christian authority. |

|

|

Portrait as Hercules 190 CE |

Marcus Aurelius bucks the expectation of an un-related heir by raising his son Commodus to Co-Emperor. Upon Marcus Aurelius’ death, Commodus assumes full control of the empire, but proves to be more interested in self-indulgence than proper governance. His Portrait as Hercules exemplifies this abuse. Commodus will be assassinated, throwing Rome into chaos. |

|

|

The Empire at home and abroad |

The infrastructure of Rome defines the empire in Italy and abroad. Roads, bridges and Aqueducts unite the known world. As Rome expands in the east, its monuments take on an orientelizing character. |

|

|

Funerary Art |

As the empire expands, it absorbs several mystery cults from the east, and thus inhumation (burial) becomes the norm for Rome, replacing cremation. In Egypt, encaustic mummy portraits are fashionable. Throughout Europe, sarcophagi with relief panels are popular, and customizable to budget. |

|

|

Al-Khazneh (“Treasury"), Petra, Jordan, second century CE |

This provincial rock-hewn building utilizes standard Greek architectural vocabulary, but the elements are arranged in way that ignores Classical rules–the further from Rome, the more experimental and unorthodox the architecture. |

|

|

The Severans (193-235 CE) |

Septimius Severus emerges from the civil wars as Rome’s first African emperor. He bequeaths Rome to his sons Geta and Caracalla, but Caracalla murders Geta, along with thousands of Romans loyal to him. |

|

|

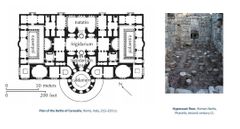

Baths of Caracalla |

Following Caracalla’s citywide purge, he dedicates a massive public bath complex. The structure is symmetrical. Constructed of concrete groin vaults, the baths include a Natatio—swimming pool; tepidarium—warm bath; caldarium—hot water bath; frigidarium—cold water bath. There are also palaestrae—exercise courts; lecture halls, libraries, vending areas and changing rooms, complete with amenities like saunas and steam rooms. The vaults are fully decorated with expensive coffering and marble; floors decorated with mosaics. |

|

|

Weary Herakles |

Colossal statues, including the Weary Herakles and the Diskobolos populate the space. All Romans may recreate here, regardless of statues. Understand that the entire project is a massive public bribe. |

|

|

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (284-306 CE) |

Rather than let Rome succumb to regional rivalry, Diocletian establishes the Tetrarchy--rule by four: two Augusti and two junior Caesars. The empire is thus divided into Eastern and Western realms, with four separate capitals in the North and South. |

|

|

Portraits of the four tetrarchs |

The porphyry statues depict the Tetrarchs devoid of individuality, each figure coexisting in peace, harmony and equanimity. Anticlassicism of the Late Imperial style is seen in abstraction and stylization of figures, conveying the complete unity of the Empire, despite rule by four. |

|

|

Constantine and Christianity (306-337 CE) |

After the immediate destabilization of the tetrarchy after Diocletian’s retirement and the ensuing civil war, Constantine begins to restore unified rule. Constantine attributed his defeat of his rival Maxentius to the intercession of the Christians’ god through the use of the Chi-Rho-Iota monogram. |

|

|

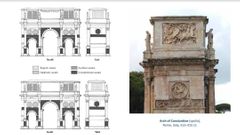

The Arch of Constantine |

The senate commemorated Constantine’s victory with an arch that appropriated Classical-styled reliefs from earlier monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, attempting to show a connection to the “good” emperors. Constantine’s own reliefs are hieratic, stiff and stylized- the images of largess are straight-forward and direct, with little classicizing metaphor. No Christian images are present, as not to offend the majority pagan population. |

|

|

Dura-Europos, Syria |

When the Synagogue at Dura-Europos was excavated in the 20th century, it was unique archaeological evidence – a fully decorated sanctuary for the Hebrew liturgy. The city also boasts one of the earliest surviving Christian community spaces. |

|

|

Synagogue (245-256) |

The long buried Hebrew temple contains wall-paintings with scenes from the Torah. These are significant, as Judaism was long thought to be aniconic (no icons/imagery). At Dura-Europos, images served to instruct, complimenting readings from the Hebrew scripture. The style borrows liberally from Greco-Roman naturalism and illusionism, but the main figures are stylized and abstracted and with hierarchical scale, consistent with the late antique style of the Tetrarchy. The Hebrew God only appears as a disembodied hand. |

|

|

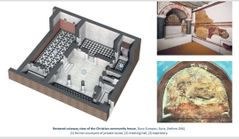

Christian Community House (domus ecclesiae) of Dura-Europos (before 270) |

A remodeled private residence accommodated a meeting hall, dining room and baptistery. This domus ecclesia, or house church, pre-dates the establishment of Christianity as the State Religion so the space is relatively modest. The baptistery carries wall painting that alludes to Original Sin, and Christ as the Good Shepherd. |

|

|

Sarcophagi (2nd-3rd centuries) |

Late antique coffins carry reliefs carved with Christian themes and biblical subject matter from both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. Stock poses such as the recumbent figure are fluid, appearing in Jewish (Jonah) as well as Pagan (Ariadne, Endymion) art. Freestanding statues are rarer, but do exist, most often depicting Jesus as the Good Shepherd. |

|

|

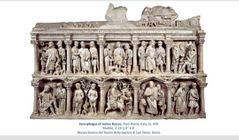

The Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (359) |

This coffin of an elite, Early-Christian convert features vignettes such as the Sacrifice of Abraham, and the Misery of Job, which Christians single out as Hebrew narratives that pre-figure Christ’s sacrifice. Also included are scenes of persecution from the New Testament such as the arrests of Christ Peter, and Paul. Together these scenes refer to an overall theme of suffering that, through faith, leads to salvation. |

|

|

The mosaics in Santa Costanza (337-351) |

Motifs adapted from the Greco-Roman world and modified for a new symbolic content. The mosaics in Santa Costanza (337-351) have vine, grape, and wine motifs typically associated with the pagan god Bacchus. Here they suggest the Eucharist, that is, the wine that Christ transforms into his blood at the Last Supper. According to the faith his priests subsequently transform bread and wine into the Corpus Christi during the mass through the miracle of Transubstantiation. |

|

|

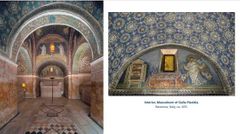

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (ca. 425) |

Features barrel-vaulted arms, and a domecovered crossing. The exterior is plain, but the interior is adorned with mosaics including an image of St. Lawrence the Martyr, and Christ as the Good Shepherd. Some Classical Greco-Roman naturalism lingers. Christ acquires more imperial attributes as Christianity becomes an Imperial cult: purple and gold robes, a halo, and a shepherd’s staff looking more like a scepter. |

|

|

The Suicide of Judas and Crucifixion of Christ |

Ivory plaques featured scenes carved in relief and painted. The Suicide of Judas and Crucifixion of Christ, is another response to the previously taboo image of Christ on the Cross: juxtaposition. Compared to Judas’ limp, impotent body, Christ defies both gravity and death. |

|

|

Byzantine Art and Architecture (313) |

In 313, the Edict of Milan ended persecution of Christians. Constantine subsequently moves his court from Italy to Byzantium, creating a new seat of power in the East, a “New Rome”, a Christian Rome, centered on the city he founded, Constantinople. In 395, the Roman Empire is divided between West and East (the Byzantine Empire). Rome’s capitals in the West are challenged and invaded; the empire disintegrates throughout the fifth century. Meanwhile New Rome (Constantinople) flourishes and expands, even periodically reasserting control in Italy. |

|

|

Early Byzantine Art and Architecture (527-726) Justinian as World Conqueror |

The Byzantine Empire is a theocracy: there is unity between military, state and church. Justinian’s reign sees the codification of civil and church law. This is best exemplified in the luxury item Justinian as World Conqueror, mid 6th c. The ivory plaques depict the Byzantine emperor as an equestrian, dominating the world, complete with personifications of Africa, Asia, Europe, and even the earth itself. This power is confirmed by Nike, but the true source of Justinian’s strength is Jesus Christ, appearing in a far more imperial guise. |

|

|

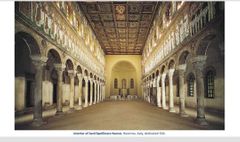

San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, 526-547 |

In an attempt to establish its connection to the Byzantine east, this Italian church is centrally-planned and octagonal (as opposed to the longitudinal basilica associated with the west), with an intricate interior featuring elaborate mosaics. The most politically important images symbolize Justinian’s piety–his divine right to rule is bolstered by the Church; the power of the state in turn legitimizes the Church. |

|

|

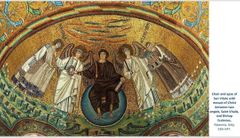

The Apse mosaic |

Depicts Christ with angels, Saint Vitalis and Bishop Ecclesius. Christ dons purple robes and enthroned on a blue sphere, showing dominion over the world. Vitalis the martyr receives a crown. Ecclesius offers a votive of the church. The scene takes place in paradise. |

|

|

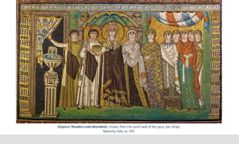

Emporer Justinian Bishop Maximanious and attendents (Mosaic on lower wall) |

Shows Justinian wearing crown, robes, and halo (the original use of the halo was to indicate the emperor); he bears instruments of the liturgy. State officials and army stand on one side and the clergy on the other (Bishop Maximianus). The figures are frontal and interlocked; with staring eyes they seem to float against a golden backdrop; they are heavenly, weightless and ethereal, casting no shadows. |

|

|

Empress Theodora and attendents (Mosaic across from Justinian) |

Shows Empress Theodora with chalice for the wine of the Eucharist, she wears a robe adorned with the magi, however she will not deliver her gift directly: even as the most powerful woman in the world, she will still be relegated to the gallery level of the church, as per gender norms of the culture. |

|

|

Lateral mosaics show |

Hebrew Bible scenes. From the Christian perspective, these are Old Testament prefigurations of the Eucharist. |

|

|

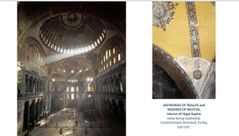

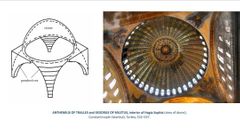

Hagia Sophia in Constantinople |

This gigantic, domed church is designed by Greek architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletius, who are in fact a mathematician and physicist, respectively. The plan combines centralized and longitudinal features. Like the Pantheon, the domed structure acts as a microcosm for creation itself, with the lower walls carrying stone revetments quarried from all over the empire. |

|

|

Pendentives |

Triangular pieces of masonry transition the rounded dome to a square base; carries weight of dome; transferring weight to one of four massive piers. Aided by clerestory windows, the pendentives create the illusion that dome floats above the nave. |

|

|

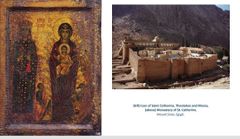

The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai in Egypt |

The church’s apse mosaic depicts the Transfiguration. Christ surrounded by a mandorla reveals his divinity in the presence of Moses and Elijah. The figures are flat, weightless, casting no shadows and are set against an otherworldly gold background. The scene represents the succession of Christianity over Judaism, a message particularly loaded at Mt. Sinai. |

|

|

Theotokos and Christ Child |

Icons of a religious figures painted on a portable wooden panel (Christ, Virgin Mary, saints). However, these objects were intended to be used as tools: conduits to the divine that focus prayer and often taken on holy lore of their own. From St. Catherine’s monastery produced a particularly famous Theotokos and Christ Child. Theotokos is an honorific title meaning Vessel of God. It is in this era that the Church elevates Mary to new heights: she is no longer seen as merely the mother of Jesus, but the Mother of God, and thus becomes the personification of the Church itself. The earliest icons are rare because of the iconoclast movement in 8th-9th centuries. |

|

|

Iconoclasm (726-843) Khludov Psalter |

iconoclasts (literally, the breakers of images) take the Second Commandment against idolatry literally. The State mandates bans on images, sanctioning their destruction. Iconophiles (lovers of images) see the pictures as didactic, and particularly useful in an era of rampant illiteracy. Iconophiles further compare the iconoclasts to the Pharisees and Romans who persecute and brutalize Christ, as in the Khludov Psalter. Iconophiles restore the veneration of icons for good by the tenth century. |

|

|

The motif of Christ as Pantocrator (Greek for “ruler of all”), Cathedral at Monreale |

The motif of Christ as Pantocrator (Greek for “ruler of all”) recurs in many Orthodox churches including: Katholikon of Hosios Loukas; Church of the Dormition at Daphni; Cathedral at Monreale, Sicily. The Pantocrator combines aspects of God the Father with Christ as the Last Judge of humankind. Conveys omnipotence with imposing, omniscient eyes. Like the dome at Hagia Sophia, the apse becomes the realm of heaven. Below, in each of these examples are senes depicting Christ’s life on earth, including the Annunciation, Nativity, Baptism and Transfiguration. |

|

|

Church of Dormition at Daphni |

Contains a revised image of the Crucifixion, 1090-1100, Christ is now visibly lifeless on the cross, subject to gravity. Below are the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist–situating the scene in gospel narrative, however other elements such as the skull at the base of the cross reference tradition: Christ dies to redeem Original Sin, thus it is Adam’s skull. The gestures of John and the Virgin suggest the larger metaphor for the Church on earth. The scene of course takes place amidst the now signature gold ground. |

|

|

St. Mark’s in Venice |

The Venetians plundered Constantinople and Greece during the Fourth Crusade. However before the betrayal, Venice was actually a protectorate of the Byzantine emperors and thus already embraced many eastern motifs: the plan of San Marco features a central dome over the crossing, with four domes clustered around to create a Greek cross shape, after the Constantinian Church of the Apostles in Constantinople. The interior walls are sheathed in gilded copper and decorated with rich mosaics. Weightless figures hover over the golden surface. Narrative scenes depict the crucifixion and Anastasis. |

|

|

Four different Roman wall style paintings |

1. illusionistic painting to simulate marble or expensive stone. 2. modeled figures and/or illusionistic scenes of architectural vistas or landscapes. The appearance of space is achieved through linear perspective and atmospheric perspective. Second style often incorporates figures who appear three-dimensional though modeling. This is probably the most influential style on later Renaissance era painters as it exemplifies the Roman interest in observing and celebrating the natural world. 3. Solid-colored backgrounds, thin decorative columns frame tiny landscapes that seem to float against background, acknowledging the wall and embracing the graphic, two-dimensional quality. 4. Combines elements from previous styles. Included Greek mythological scenes, “portraits”, landscapes and still-life. |