![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

36 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

- 3rd side (hint)

|

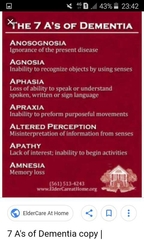

What are the cognitive deficits seen in dementia |

Amnesia Apraxia Aphasia Agnosia

|

|

|

|

What are the reversible causes of dementia |

Alcohol or drug abuseTumorsSubdural hematomas, blood clots beneath the outer covering of the brainNormal-pressure hydrocephalus, a buildup of fluid in the brainMetabolic disorders such as a vitamin B12 deficiencyhypothyroidism hypoglycemiaHIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) |

|

|

|

What are the irreversible causes of dementia |

Alzheimer disease Vascular dementia Lewybody dementia Frontotemporal dementia Parkinsons dementia |

|

|

|

What are the domains of cognitive function |

Attention Decision making General fund of knowledge Judgment Language Memory Perception Planning Reasoning Visuospatial |

|

|

|

Dementia causes |

VANISHED MnemonicV: vitamin deficiency: B1, B6, B12, folateA: autoimmune: cerebral vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosusN: normal pressure hydrocephalus, neoplasiaI: infection: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, herpes simplex encephalitis, prion diseases, tertiary syphilis, HIV/AIDS, PMLS: substance abuse, serum abnormalities e.g. hyperammonaemia, uraemia, Wilson diseaseH: hormones: hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidismE: electrolyte disturbancesD: depression (so-called pseudodementia) |

|

|

|

What are the Risk factors for dementia |

Alcohol Tobacco Physical inactivity Depression Diet Life events Cardiovascular risk factors |

|

|

|

Q |

With regard to DLBVisual hallucinations are rare Step wise progression is classical Parkinsonian symptoms are common Cholinesterase inhibitors are considered in the Mx Haloperidol is safe in the Mx of behavioural disturbance

|

|

|

|

What are the types of dementia |

Alzheimer disease Vascular dementia Lewybody dementia Frontotemporal dementia |

|

|

|

What is DLB |

progressive, degenerative dementia of unknown etiology. Affected patients generally present with dementia preceding motor signs, particularly with visual hallucinations and episodes of reduced responsiveness. |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

What are the clinical features that help distinguish DLB from Alzheimer disease |

•Fluctuations in cognitive function with varying levels of alertness and attention (eg, excessive daytime drowsiness despite adequate nighttime sleep or daytime sleep >2 hours, staring into space for long periods, episodes of disorganized speech) •Visual hallucinations •Parkinsonian motor features •Relatively early extrapyramidal features (vs may occur late in Alzheimer disease) •Anterograde memory loss: May be less prominent (vs prominent early sign in Alzheimer disease) •More prominent executive function deficits and visuospatial impairment (eg, Stroop, digit span backwards)

|

|

|

|

When should we consider DLB over Parkinson disease |

When dementia precedes motor signs, particularly with visual hallucinations and episodes of reduced responsiveness, the diagnosis of DLB should be considered. |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

What is the epidemiology like in DLB |

Most studies suggest that DLB is slightly more common in men than in women.DLB is a disease of late middle age and old age. The aforementioned study in southwestern France found that the incidence of DLB increased continuously with advancing age, whereas that of Parkinson disease decreased after age 85 years.

|

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

What is the progression of DLB like |

DLB is a disorder of inexorable progression. The rate of progression varies, and some investigators think that progression is faster than that of Alzheimer disease. Patients eventually die from complications of immobility, poor nutrition, and swallowing difficulties |

|

|

|

Q |

I |

|

|

|

Q |

Recognised findings in dementiaVisuo spatial dysfunctionDelusionsWord fimding difficultyApraxiaVisual hallucinations |

|

|

|

What is dementia of Lewy body |

Dementia is chronic, global, usually irreversible deterioration of cognition. Diagnosis is clinical; laboratory and imaging tests are usually used to identify treatable causes. Treatment is supportive. Cholinesterase inhibitors can sometimes temporarily improve cognitive function. Dementia may occur at any age but affects primarily the elderly. It accounts for more than half of nursing home admissions.

(see Table: Differences Between Delirium and Dementia*).EtiologyDementias may result from primary diseases of the brain or other conditions (see Table: Classification of Some Dementias).The most common types of dementia areAlzheimer diseaseVascular dementiaLewy body dementiaFrontotemporal dementiasHIV-associated dementiaDementia also occurs in patients with Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, other prion disorders, and neurosyphilis. Patients can have > 1 type (mixed dementia).Some structural brain disorders (eg, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma), metabolic disorders (eg, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency), and toxins (eg, lead) cause a slow deterioration of cognition that may resolve with treatment. This impairment is sometimes called reversible dementia, but some experts restrict the term dementia to irreversible cognitive deterioration.Depression may mimic dementia (and was formerly called pseudodementia); the 2 disorders often coexist. However, depression may be the first manifestation of dementia.Age-associated memory impairment refers to changes in cognition that occur with aging. The elderly have a relative deficiency in recall, particularly in speed of recall, compared with recall during their youth. These changes do not affect daily functioning and thus do not indicate dementia. However, the earliest manifestations of dementia are very similar.Mild cognitive impairment causes greater memory loss than age-associated memory impairment; memory and sometimes other cognitive functions are worse in patients with this disorder than in age-matched controls, but daily functioning is typically not affected. In contrast, dementia impairs daily functioning. Up to 50% of patients with mild cognitive impairment develop dementia within 3 yr.Any disorder may exacerbate cognitive deficits in patients with dementia. Delirium often occurs in patients with dementia.Drugs, particularly benzodiazepines and anticholinergics (eg, some tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, benztropine), may temporarily cause or worsen symptoms of dementia, as may alcohol, even in moderate amounts. New or progressive kidney or liver failure may reduce drug clearance and cause drug toxicity after years of taking a stable drug dose (eg, of propranolol).Prion mechanisms appear to be involved in most or all neurodegenerative disorders that first manifest in the elderly. A normal cellular protein sporadically (or via an inherited mutation) becomes misfolded into a pathogenic form or prion. The prion then acts as a template, causing other proteins to misfold similarly. This process occurs over years and in many parts of the CNS. Many of these prions become insoluble and, like amyloid, cannot be readily cleared by the cell. Evidence implies prion or similar mechanisms in Alzheimer disease (strongly), as well as in Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, frontotemporal dementia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. These prions are not as infectious as those in Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, but they can be transmitted.Classification of Some DementiasClassificationExamplesBeta-amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tanglesAlzheimer diseaseTau abnormalitiesChronic traumatic encephalopathyCorticobasal ganglionic degenerationFrontotemporal dementia (including Pick disease)Progressive supranuclear palsyAlpha-synuclein abnormalitiesLewy body dementiaParkinson disease dementiaHuntingtin gene mutationHuntington diseaseCerebrovascular diseaseVascular dementias:Binswanger diseaseLacunar diseaseMulti-infarct dementiaStrategic single-infarct dementiaIngestion of drugs or toxinsAlcohol-associated dementiaDementia due to exposure to heavy metalsInfectionsFungal: Dementia due to cryptococcosisSpirochetal: Dementia due to syphilis or Lyme diseaseViral:HIV-associated dementia, postencephalitis syndromesPrion disordersAlzheimer diseaseAmyotrophic lateral sclerosisCreutzfeldt-Jakob diseaseFrontotemporal dementiaHuntington diseaseParkinson diseaseVariant Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseaseStructural brain disordersBrain tumorsChronic subdural hematomasNormal-pressure hydrocephalusOther potentially reversible disordersDepressionHypothyroidismVitamin B12 deficiencySymptoms and Signs(See also Behavioral and Psychologic Symptoms of Dementia.)Dementia impairs cognition globally. Onset is gradual, although family members may suddenly notice deficits (eg, when function becomes impaired). Often, loss of short-term memory is the first sign. At first, early symptoms may be indistinguishable from those of age-associated memory impairment or mild cognitive impairment, but then progression becomes apparent.Although symptoms of dementia exist in a continuum, they can be divided intoEarlyIntermediateLatePersonality changes and behavioral disturbances may develop early or late. Motor and other focal neurologic deficits occur at different stages, depending on the type of dementia; they occur early in vascular dementia and late in Alzheimer disease. Incidence of seizures is somewhat increased during all stages.Psychosis—hallucinations, delusions, or paranoia—occurs in about 10% of patients with dementia, although a higher percentage may experience these symptoms temporarily.Early dementia symptomsRecent memory is impaired; learning and retaining new information become difficult. Language problems (especially with word finding), mood swings, and personality changes develop. Patients may have progressive difficulty with independent activities of daily living (eg, balancing their checkbook, finding their way around, remembering where they put things). Abstract thinking, insight, or judgment may be impaired. Patients may respond to loss of independence and memory with irritability, hostility, and agitation.Functional ability may be further limited by the following:Agnosia: Impaired ability to identify objects despite intact sensory functionApraxia: Impaired ability to do previously learned motor activities despite intact motor functionAphasia: Impaired ability to comprehend or use languageAlthough early dementia may not compromise sociability, family members may report strange behavior accompanied by emotional lability.Intermediate dementia symptomsPatients become unable to learn and recall new information. Memory of remote events is reduced but not totally lost. Patients may require help with basic activities of daily living (eg, bathing, eating, dressing, toileting).Personality changes may progress. Patients may become irritable, anxious, self-centered, inflexible, or angry more easily, or they may become more passive, with a flat affect, depression, indecisiveness, lack of spontaneity, or general withdrawal from social situations.Behavior disorders may develop: Patients may wander or become suddenly and inappropriately agitated, hostile, uncooperative, or physically aggressive.By this stage, patients have lost all sense of time and place because they cannot effectively use normal environmental and social cues. Patients often get lost; they may be unable to find their own bedroom or bathroom. They remain ambulatory but are at risk of falls or accidents secondary to confusion.Altered sensation or perception may culminate in psychosis with hallucinations and paranoid and persecutory delusions.Sleep patterns are often disorganized.Late (severe) dementia symptomsPatients cannot walk, feed themselves, or do any other activities of daily living; they may become incontinent. Recent and remote memory is completely lost. Patients may be unable to swallow. They are at risk of undernutrition, pneumonia (especially due to aspiration), and pressure ulcers. Because they depend completely on others for care, placement in a long-term care facility often becomes necessary. Eventually, patients become mute.Because such patients cannot relate any symptoms to a physician and because elderly patients often have no febrile or leukocytic response to infection, a physician must rely on experience and acumen whenever a patient appears ill.End-stage dementia results in coma and death, usually due to infection.DiagnosisDifferentiation of delirium from dementia by history and neurologic examination (including mental status)Identification of treatable causes clinically and by laboratory testing and neuroimagingSometimes formal neuropsychologic testingRecommendations about diagnosis of dementia are available from the American Academy of Neurology.Distinguishing type or cause of dementia can be difficult; definitive diagnosis often requires postmortem pathologic examination of brain tissue. Thus, clinical diagnosis focuses on distinguishing dementia from delirium and other disorders and identifying the cerebral areas affected and potentially reversible causes.Dementia must be distinguished from the following:Delirium: Distinguishing between dementia and delirium is crucial (because delirium is usually reversible with prompt treatment) but can be difficult. Attention is assessed first. If a patient is inattentive, the diagnosis is likely to be delirium, although advanced dementia also severely impairs attention. Other features that suggest delirium rather than dementia (eg, duration of cognitive impairment—see Table: Differences Between Delirium and Dementia*) are determined by the history, physical examination, and tests for specific causes.Age-associated memory impairment: Memory impairment does not affect daily functioning. If affected people are given enough time to learn new information, their intellectual performance is good.Mild cognitive impairment: Memory and/or other cognitive functions are impaired, but impairment is not severe enough to interfere with daily activities.Cognitive symptoms related to depression: This cognitive disturbance resolves with treatment of depression. Depressed older patients may experience cognitive decline, but unlike patients with dementia, they tend to exaggerate their memory loss and rarely forget important current events or personal matters. Neurologic examinations are normal except for signs of psychomotor slowing. When tested, patients with depression make little effort to respond, but those with dementia often try hard but respond incorrectly. When depression and dementia coexist, treating depression does not fully restore cognition.Clinical criteriaThe most recent National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association diagnostic guidelines specify that a general diagnosis of dementia requires all of the following:Cognitive or behavioral (neuropsychiatric) symptoms interfere with the ability to function at work or do usual daily activities.These symptoms represent a decline from previous levels of functioning.These symptoms are not explained by delirium or a major psychiatric disorder.The cognitive or behavioral impairment should be diagnosed based on a combination of history from the patient and from someone who knows the patient plus assessment of cognitive function (a bedside mental status examination or, if bedside testing is inconclusive, formal neuropsychologic testing). In addition, the impairment should involve ≥ 2 of the following domains:Impaired ability to acquire and remember new information (eg, asking repetitive questions, frequently misplacing objects or forgetting appointments)Impaired reasoning and handling of complex tasks and poor judgment (eg, being unable to manage a bank account, making poor financial decisions)Language dysfunction (eg, difficulty thinking of common words, errors speaking and/or writing)Visuospatial dysfunction (eg, inability to recognize faces or common objects)Changes in personality, behavior, or comportmentIf cognitive impairment is confirmed, history and physical examination should then focus on signs of treatable disorders that cause cognitive impairment (eg, vitamin B12 deficiency, neurosyphilis, hypothyroidism, depression—see Table: Causes of Delirium).Assessment of cognitive functionThe Mini-Mental Status Examination (see Examination of Mental Status) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is often used as a bedside screening test. When delirium is absent, the presence of multiple deficits, particularly in patients with an average or a higher level of education, suggests dementia. The best screening test for memory is a short-term memory test (eg, registering 3 objects and recalling them after 5 min); patients with dementia fail this test. Another test of mental status assesses the ability to name multiple objects within categories (eg, lists of animals, plants, or pieces of furniture). Patients with dementia struggle to name a few; those without dementia easily name many.Neuropsychologic testing should be done when history and bedside mental status testing are not conclusive. It evaluates mood as well as multiple cognitive domains. It takes 1 to 3 h to complete and is done or supervised by a neuropsychologist. Such testing helps primarily in differentiating the following:Age-associated memory impairment, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia, particularly when cognition is only slightly impaired or when the patient or family members are anxious for reassuranceDementia and focal syndromes of cognitive impairment (eg, amnesia, aphasia, apraxia, visuospatial difficulties, impairment of executive function) when the distinction is not clinically evidentTesting may also help characterize specific deficits due to dementia, and it may detect depression or a personality disorder that is contributing to poor cognitive performance.Laboratory testingTests should include thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12 levels. Routine CBC and liver function tests are sometimes recommended, but yield is very low.If clinical findings suggest a specific disorder, other tests (eg, for HIV or syphilis) are indicated. Lumbar puncture is rarely needed but should be considered if a chronic infection or neurosyphilis is suspected. Other tests may be used to exclude causes of delirium.Biomarkers for Alzheimer disease can be useful in research settings but are not yet routine in clinical practice. For example, in CSF, the tau level increases and beta-amyloid decreases as Alzheimer disease progresses. Also, routine genetic testing for the apolipoprotein E4 allele (apo ε4) is not recommended.(For people with 2 ε4 alleles, the risk of developing Alzheimer disease by age 75 is 10 to 30 times that for people without the allele.)NeuroimagingCT or MRI should be done in the initial evaluation of dementia or after any sudden change in cognition or mental status. Neuroimaging can identify potentially reversible structural disorders (eg, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, brain tumors, subdural hematoma) and certain metabolic disorders (eg, Hallervorden-Spatz disease, Wilson disease).Occasionally, EEG is useful (eg, to evaluate episodic lapses in attention or bizarre behavior).PET with fluorine-18 (18F)–labeled deoxyglucose (fluorodeoxyglucose, or FDG) or single-photon emission CT (SPECT) can provide information about cerebral perfusion patterns and help with differential diagnosis (eg, in differentiating Alzheimer disease from frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body dementia).Amyloid radioactive tracers that bind specifically to beta-amyloid plaques (eg, florbetapir, flutemetamol, florbetaben) have been used with PET to image amyloid plaques in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. This testing should be used when the cause of cognitive impairment (eg, mild cognitive impairment or dementia) is uncertain after a comprehensive evaluation and when Alzheimer disease is a diagnostic consideration. Determining amyloid status via PET is expected to increase the certainty of diagnosis and management.PrognosisDementia is usually progressive. However, progression rate varies widely and depends on the cause. Dementia shortens life expectancy, but survival estimates vary.TreatmentMeasures to ensure safetyProvision of appropriate stimulation, activities, and cues for orientationElimination of drugs with sedating or anticholinergic effectsPossibly cholinesterase inhibitors and memantineAssistance for caregiversArrangements for end-of-life careRecommendations about treatment of dementia are available from the American Academy of Neurology. Measures to ensure patient safety and to provide an appropriate environment are essential to treatment, as is caregiver assistance. Several drugs are available.Patient safetyOccupational and physical therapists can evaluate the home for safety; the goals are toPrevent accidents (particularly falls)Manage behavior disordersPlan for change as dementia progressesHow well patients function in various settings (ie, kitchen, automobile) should be evaluated using simulations. If patients have deficits and remain in the same environment, protective measures (eg, hiding knives, unplugging the stove, removing the car, confiscating car keys) may be required. Some states require physicians to notify the Department of Motor Vehicles of patients with dementia because at some point, such patients can no longer drive safely.If patients wander, signal monitoring systems can be installed, or patients can be registered in the Safe Return program. Information is available from the Alzheimer’s Association.Ultimately, assistance (eg, housekeepers, home health aides) or a change of environment (living facilities without stairs, assisted-living facility, skilled nursing facility) may be indicated.Environmental measuresPatients with mild to moderate dementia usually function best in familiar surroundings.Whether at home or in an institution, the environment should be designed to help preserve feelings of self-control and personal dignity by providing the following:Frequent reinforcement of orientationA bright, cheerful, familiar environmentMinimal new stimulationRegular, low-stress activitiesOrientation can be reinforced by placing large calendars and clocks in the room and establishing a routine for daily activities; medical staff members can wear large name tags and repeatedly introduce themselves. Changes in surroundings, routines, or people should be explained to patients precisely and simply, omitting nonessential procedures. Patients require time to adjust and become familiar with the changes. Telling patients about what is going to happen (eg, about a bath or feeding) may avert resistance or violent reactions. Frequent visits by staff members and familiar people encourage patients to remain social.The room should be reasonably bright and contain sensory stimuli (eg, radio, television, night-light) to help patients remain oriented and focus their attention. Quiet, dark, private rooms should be avoided.Activities can help patients function better; those related to interests before dementia began are good choices. Activities should be enjoyable, provide some stimulation, but not involve too many choices or challenges.Exercise to reduce restlessness, improve balance, and maintain cardiovascular tone should be done daily. Exercise can also help improve sleep and manage behavior disorders.Occupational therapy and music therapy help maintain fine motor control and provides nonverbal stimulation.Group therapy (eg, reminiscence therapy, socialization activities) may help maintain conversational and interpersonal skills.DrugsEliminating or limiting drugs with CNS activity often improves function. Sedating and anticholinergic drugs, which tend to worsen dementia, should be avoided.The cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine are somewhat effective in improving cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer disease or Lewy body dementia and may be useful in other forms of dementia. These drugs inhibit acetylcholinesterase, increasing the acetylcholine level in the brain.Memantine, an NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) antagonist, may help slow the loss of cognitive function in patients with moderate to severe dementia and may be synergistic when used with a cholinesterase inhibitor.Drugs to control behavior disorders (eg, antipsychotics) have been used.Patients with dementia and signs of depression should be treated with nonanticholinergic antidepressants, preferably SSRIs.Caregiver assistanceImmediate family members are largely responsible for care of a patient with dementia (see Family Caregiving for the Elderly). Nurses and social workers can teach them and other caregivers how to best meet the patient’s needs (eg, how to deal with daily care and handle financial issues); teaching should be ongoing. Other resources (eg, support groups, educational materials, Internet web sites) are available.Caregivers may experience substantial stress. Stress may be caused by worry about protecting the patient and by frustration, exhaustion, anger, and resentment from having to do so much to care for someone. Health care practitioners should watch for early symptoms of caregiver stress and burnout and, when needed, suggest support services (eg, social worker, nutritionist, nurse, home health aide).If a patient with dementia has an unusual injury, the possibility of elder abuse should be investigated.End-of-life issuesBecause insight and judgment deteriorate in patients with dementia, appointment of a family member, guardian, or lawyer to oversee finances may be necessary. Early in dementia, before the patient is incapacitated, the patient’s wishes about care should be clarified, and financial and legal arrangements (eg, durable power of attorney, durable power of attorney for health care) should be made. When these documents are signed, the patient’s capacity should be evaluated, and evaluation results recorded. Decisions about artificial feeding and treatment of acute disorders are best made before the need develops.In advanced dementia, palliative measures may be more appropriate than highly aggressive interventions or hospital care.Key PointsDementia, unlike age-associated memory loss and mild cognitive impairment, causes cognitive impairments that interfere with daily functioning.Be aware that family members may report sudden onset of symptoms only because they suddenly recognized gradually developing symptoms.Consider reversible causes of cognitive decline, such as structural brain disorders (eg, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma), metabolic disorders (eg, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency), drugs, depression, and toxins (eg, lead).Do bedside mental status testing and, if necessary, formal neuropsychologic testing to confirm that cognitive function is impaired in ≥ 2 domains.Recommend or help arrange measures to maximize patient safety, to provide a familiar and comfortable environment for the patient, and to provide support for caregivers.Consider adjunctive drug therapy, and recommend making end-of-life arrangements.More InformationLast full review/revision March 2018 by Juebin Huang, MD, PhDResources In This ArticleDrugs Mentioned In This ArticleDelirium and DementiaOverview of Delirium and DementiaDeliriumDementiaAlzheimer DiseaseBehavioral and Psychologic Symptoms of DementiaChronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)HIV-Associated DementiaLewy Body Dementia and Parkinson Disease DementiaNormal–Pressure HydrocephalusVascular DementiaDeliriumAlzheimer DiseaseTap to switch to the Consumer VersionAlso of InterestMManual

|

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Q |

|

|

|

Q |

Merck Manuals Professional EditionMerck ManualsFree - In Google PlayView MERCK MANUALProfessional VersionTap to switch to the Consumer VersionShareEmailLinkedInFacebookGoogle+TwitterLewy Body Dementia and Parkinson Disease DementiaBy Juebin Huang, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Neurology, Memory Impairment and Neurodegenerative Dementia (MIND) Center, University of Mississippi Medical Center CLICK HERE FOR Patient EducationLewy body dementia is chronic cognitive deterioration characterized by cellular inclusions called Lewy bodies in the cytoplasm of cortical neurons. Parkinson disease dementia is cognitive deterioration characterized by Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra; it develops late in Parkinson disease.(See also Overview of Delirium and Dementia and Dementia.)Dementia is chronic, global, usually irreversible deterioration of cognition.Lewy body dementia is the 3rd most common dementia. Age of onset is typically > 60.Lewy bodies are spherical, eosinophilic, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions composed of aggregates of alpha-synuclein, a synaptic protein. They occur in the cortex of some patients with primary Lewy body dementia. Neurotransmitter levels and neuronal pathways between the striatum and the neocortex are abnormal.Lewy bodies also occur in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson disease, and dementia (Parkinson disease dementia) may develop late in the disease. About 40% of patients with Parkinson disease develop Parkinson disease dementia, usually after age 70 and about 10 to 15 yr after Parkinson disease has been diagnosed.Because Lewy bodies occur in Lewy body dementia and in Parkinson disease dementia, some experts think that the 2 disorders may be part of a more generalized synucleinopathy affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems. Lewy bodies sometimes occur in patients with Alzheimer disease, and patients with Lewy body dementia may have neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Lewy body dementia, Parkinson disease, and Alzheimer disease overlap considerably. Further research is needed to clarify the relationships among them.Both Lewy body dementia and Parkinson disease dementia have a progressive course with a poor prognosis.Dementia should not be confused with delirium, although cognition is disordered in both. The following usually helps distinguish dementia from delirium:Dementia affects mainly memory, is typically caused by anatomic changes in the brain, has slower onset, and is generally irreversible.Delirium affects mainly attention, is typically caused by acute illness or drug toxicity (sometimes life threatening), and is often reversible.Other specific characteristics also help distinguish the dementia and delirium (see Table: Differences Between Delirium and Dementia*).Symptoms and SignsLewy body dementiaInitial cognitive deterioration in Lewy body dementia resembles that in other dementias; it involves deterioration in memory, attention, and executive function and behavioral problems.Extrapyramidal symptoms (typically including rigidity, bradykinesia, and gait instability) occur (see also Overview of Movement and Cerebellar Disorders). However, in Lewy body dementia (unlike in Parkinson disease), cognitive and extrapyramidal symptoms usually begin within 1 yr of each other. Also, the extrapyramidal symptoms differ from those of Parkinson disease; in Lewy body dementia, tremor does not occur early, rigidity of axial muscles with gait instability occurs early, and deficits tend to be symmetric. Repeated falls are common.Fluctuating cognitive function is a relatively specific feature of Lewy body dementia. Periods of being alert, coherent, and oriented may alternate with periods of being confused and unresponsive to questions, usually over a period of days to weeks but sometimes during the same interview.Memory is impaired, but the impairment appears to result more from deficits in alertness and attention than in memory acquisition; thus, short-term recall is affected less than digit span memory (ability to repeat 7 digits forward and 5 backward).Patients may stare into space for long periods. Excessive daytime drowsiness is common.Visuospatial and visuoconstructional abilities (tested by block design, clock drawing, or figure copying) are affected more than other cognitive deficits.Visual hallucinations are common and often threatening, unlike the benign hallucinations of Parkinson disease. Auditory, olfactory, and tactile hallucinations are less common. Delusions occur in 50 to 65% of patients and are often complex and bizarre, compared with the simple persecutory ideation common in Alzheimer disease.Autonomic dysfunction is common, and unexplained syncope may result. Autonomic dysfunction may occur simultaneously with or occur after onset of cognitive deficits. Extreme sensitivity to antipsychotics is typical.Sleep problems are common. Many patients have rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, a parasomnia characterized by vivid dreams without the usual physiologic paralysis of skeletal muscles during REM sleep. As a result, dreams may be acted out, sometimes injuring the bed partner.Parkinson disease dementiaIn Parkinson disease dementia (unlike in Lewy body dementia), cognitive impairment that leads to dementia typically begins 10 to 15 yr after motor symptoms have appeared.Parkinson disease dementia may affect multiple cognitive domains including attention, memory, and visuospatial, constructional, and executive functions. Executive dysfunction typically occurs earlier and is more common in Parkinson disease dementia than in Alzheimer disease.Psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, delusions) appear to be less frequent and/or less severe than in Lewy body dementia.In Parkinson disease dementia, postural instability and gait abnormalities are more common, motor decline is more rapid, and falls are more frequent than in Parkinson disease without dementia.DiagnosisClinical criteriaNeuroimaging to rule out other disordersDiagnosis is clinical, but sensitivity and specificity are poor.A general diagnosis of dementia requires all of the following:Cognitive or behavioral (neuropsychiatric) symptoms interfere with the ability to function at work or do usual daily activities.These symptoms represent a decline from previous levels of functioning.These symptoms are not explained by delirium or a major psychiatric disorder.Evaluation of cognitive function involves taking a history from the patient and from someone who knows the patient plus doing a bedside mental status examinationor, if bedside testing is inconclusive, formal neuropsychologic testing.Diagnosis of Lewy body dementia is considered probable if 2 of the following 3 features are present and is considered possible if only one is present:Fluctuations in cognitionVisual hallucinationsParkinsonismSupportive evidence consists of repeated falls, syncope, REM sleep disorder, and sensitivity to antipsychotics.Overlap of symptoms in Lewy body dementia and Parkinson disease dementia may complicate diagnosis:When motor deficits (eg, tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity) precede and are more severe than cognitive impairment, Parkinson disease dementia is usually diagnosed.When early cognitive impairment (particularly executive dysfunction) and behavioral disturbances predominate, Lewy body dementia is usually diagnosed.Because patients with Lewy body dementia often have impaired alertness, which is more characteristic of delirium than dementia, evaluation for delirium should be done, particularly for common causes such asDrugs, particularly anticholinergics, psychoactive drugs, and opioidsDehydrationInfectionCT and MRI show no characteristic changes but are helpful initially in ruling out other causes of dementia. PET with fluorine-18 (18F)–labeled deoxyglucose (fluorodeoxyglucose, or FDG) and single-photon emission CT (SPECT) with 123I-FP-CIT (N-3-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-[4-iodophenyl]-tropane), a fluoroalkyl analog of cocaine, may help identify Lewy body dementia but are not routinely done.Definitive diagnosis requires autopsy samples of brain tissue.TreatmentSupportive careTreatment is generally supportive. For example, the environment and should be bright, cheerful, and familiar, and it should be designed to reinforce orientation (eg, placement of large clocks and calendars in the room). Measures to ensure patient safety (eg, signal monitoring systems for patients who wander) should be implemented.Troublesome symptoms can be treated.DrugsKey PointsBecause Lewy bodies occur in Lewy body dementia and in Parkinson disease, some experts hypothesize that the 2 disorders are part of the same synucleinopathy affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems.Suspect Lewy body dementia if dementia develops nearly simultaneously with parkinsonian features and when dementia is accompanied by fluctuations in cognition, loss of attention, psychiatric symptoms (eg, visual hallucinations; complex, bizarre delusions), and autonomic dysfunction.Suspect Parkinson disease dementia if dementia begins years after parkinsonian features, particularly if executive dysfunction occurs early.Consider use of rivastigmine and sometimes other cholinesterase inhibitors to try to improve cognition. |

|

|

|

What |

Dementias can be classified in several ways :Alzheimer or non-Alzheimer type Cortical or subcortical Irreversible or potentially reversible Common or rare |

|

|

|

Q |

W |

|

|

|

What |

W |

|

|

|

Q |

W |

|

|

|

Q |

W |

|

|

|

What |

Q |

|

|

|

What |

Q |

|

|

|

What |

Merck Manuals Professional EditionMerck ManualsFree - In Google PlayView MERCK MANUALProfessional VersionTap to switch to the Consumer VersionShareEmailLinkedInFacebookGoogle+TwitterAlzheimer Disease(Alzheimer's Disease)By Juebin Huang, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Neurology, Memory Impairment and Neurodegenerative Dementia (MIND) Center, University of Mississippi Medical Center CLICK HERE FOR Patient EducationAlzheimer disease causes progressive cognitive deterioration and is characterized by beta-amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex and subcortical gray matter.(See also Overview of Delirium and Dementia and Dementia.)Alzheimer disease, a neurocognitive disorder, is the most common cause of dementia; it accounts for 60 to 80% of dementias in the elderly. In the US, an estimated 10% of people ≥ 65 have Alzheimer disease. The percentage of people with Alzheimer disease increases with age:Age 65 to 74: 3%Age 75 to 84: 17%Age ≥ 85: 32% (1)The disease is twice as common among women as among men, partly because women have a longer life expectancy. Prevalence in industrialized countries is expected to increase as the proportion of the elderly increases.Overview of Alzheimer DiseaseOverview of Alzheimer DiseaseOverview of Alzheimer DiseaseGeneral referenceEtiologyMost cases are sporadic, with late onset (≥ 65 yr) and unclear etiology. Risk of developing the disease is best predicted by age. However, about 5 to 15% of cases are familial; half of these cases have an early (presenile) onset (< 65 yr) and are typically related to specific genetic mutations.At least 5 distinct genetic loci, located on chromosomes 1, 12, 14, 19, and 21, influence initiation and progression of Alzheimer disease.Mutations in genes for the amyloid precursor protein, presenilin I, and presenilin II may lead to autosomal dominant forms of Alzheimer disease, typically with presenile onset. In affected patients, the processing of amyloid precursor protein is altered, leading to deposition and fibrillar aggregation of beta-amyloid; beta-amyloid is the main component of senile plaques, which consist of degenerated axonal or dendritic processes, astrocytes, and glial cells around an amyloid core. Beta-amyloid may also alter kinase and phosphatase activities in ways that eventually lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau and formation of neurofibrillary tangles.Other genetic determinants include the apolipoprotein (apo) E alleles (ε). Apo E proteins influence beta-amyloid deposition, cytoskeletal integrity, and efficiency of neuronal repair. Risk of Alzheimer disease is substantially increased in people with 2 ε4 alleles and may be decreased in those who have the ε2 allele. For people with 2 ε4 alleles, risk of developing Alzheimer disease by age 75 is about 10 to 30 times that for people without the allele.Variants in SORL1 may also be involved; they are more common among people with late-onset Alzheimer disease. These variants may cause the gene to malfunction, possibly resulting in increased production of beta-amyloid.The relationship of other factors (eg, low hormone levels, metal exposure) and Alzheimer disease is under study, but no definite causal links have been established.PathophysiologyThe 2 pathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer disease areExtracellular beta-amyloid deposits (in senile plaques)Intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (paired helical filaments)The beta-amyloid deposition and neurofibrillary tangles lead to loss of synapses and neurons, which results in gross atrophy of the affected areas of the brain, typically starting at the mesial temporal lobe.The mechanism by which beta-amyloid peptide and neurofibrillary tangles cause such damage is incompletely understood. There are several theories.The amyloid hypothesis posits that progressive accumulation of beta-amyloid in the brain triggers a complex cascade of events ending in neuronal cell death, loss of neuronal synapses, and progressive neurotransmitter deficits; all of these effects contribute to the clinical symptoms of dementia.Prion mechanisms have been identified in Alzheimer disease. In prion diseases, a normal cell-surface brain protein called prion protein becomes misfolded into a pathogenic form termed a prion. The prion then causes other prion proteins to misfold similarly, resulting in a marked increase in the abnormal proteins, which leads to brain damage. In Alzheimer disease, it is thought that the beta-amyloid in cerebral amyloid deposits and tau in neurofibrillary tangles have prion-like, self-replicating properties.Symptoms and SignsPatients have symptoms and signs of dementia.The most common first manifestation isLoss of short-term memory (eg, asking repetitive questions, frequently misplacing objects or forgetting appointments)Other cognitive deficits tend to involve multiple functions, including the following:Impaired reasoning, difficulty handling complex tasks, and poor judgment (eg, being unable to manage bank account, making poor financial decisions)Language dysfunction (eg, difficulty thinking of common words, errors speaking and/or writing)Visuospatial dysfunction (eg, inability to recognize faces or common objects)Alzheimer disease progresses gradually but may plateau for periods of time.Behavior disorders (eg, wandering, agitation, yelling, persecutory ideation) are common.DiagnosisSimilar to that of other dementiasFormal mental status examinationHistory and physical examinationLaboratory testingNeuroimagingGenerally, diagnosis of Alzheimer disease is similar to the diagnosis of other dementias.Evaluation includes a thorough history and standard neurologic examination. Clinical criteria are 85% accurate in establishing the diagnosis and differentiating Alzheimer disease from other forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia.Traditional diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer disease include all of the following:Dementia established clinically and documented by a formal mental status examinationDeficits in ≥ 2 areas of cognitionGradual onset (ie, over months to years, rather than days or weeks) and progressive worsening of memory and other cognitive functionsNo disturbance of consciousnessOnset after age 40, most often after age 65No systemic or brain disorders (eg, tumor, stroke) that could account for the progressive deficits in memory and cognitionHowever, deviations from these criteria do not exclude a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease, particularly because patients may have mixed dementia.The most recent (2011) National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association diagnostic guidelines (1, 2) also include biomarkers for the pathophysiologic process of Alzheimer disease:A low level of beta-amyloid in CSFBeta-amyloid deposits in the brain detected by PET imaging using radioactive tracer that binds specifically to beta-amyloid plaques (eg, Pittsburgh compound B [PiB], florbetapir)Other biomarkers indicate downstream neuronal degeneration or injury:Elevated levels of tau protein in CSFDecreased cerebral metabolism in the temporoparietal cortex measured using PET with fluorine-18 (18F)–labeled deoxyglucose (fluorodeoxyglucose, or FDG)Local atrophy in the medial, basal, and lateral temporal lobes and the medial parietal cortex, detected by MRIThese findings increase the probability that dementia is due to Alzheimer disease. However, the guidelines (1, 2) do not advocate routine use of these biomarkers for diagnosis because standardization and availability are limited at this time. Also, they do not recommend routine testing for the apo ε4 allele.Differential diagnosisDistinguishing Alzheimer disease from other dementias is difficult. Assessment tools (eg, Hachinski Ischemic Score—see Table: Modified Hachinski Ischemic Score) can help distinguish vascular dementia from Alzheimer disease. Fluctuations in cognition, parkinsonian symptoms, well-formed visual hallucinations, and relative preservation of short-term memory suggest Lewy body dementia rather than Alzheimer disease (see Table: Differences Between Alzheimer Disease and Lewy Body Dementia).Patients with Alzheimer disease are often better-groomed and neater than patients with other dementias.Modified Hachinski Ischemic ScoreFeaturePoints*Abrupt onset of symptoms2Stepwise deterioration (eg, decline-stability-decline)1Fluctuating course2Nocturnal confusion1Personality relatively preserved1Depression1Somatic complaints (eg, body aches, chest pain)1Emotional lability1History or presence of hypertension1History of stroke2Evidence of coexisting atherosclerosis (eg, PAD, MI)1Focal neurologic symptoms (eg, hemiparesis, homonymous hemianopia, aphasia)2Focal neurologic signs (eg, unilateral weakness, sensory loss, asymmetric reflexes, Babinski sign)2*Total score is determined:< 4 suggests primary dementia (eg, Alzheimer disease).4–7 is indeterminate.> 7 suggests vascular dementia.PAD = peripheral arterial disease.Differences Between Alzheimer Disease and Lewy Body DementiaFeatureAlzheimer DiseaseLewy Body DementiaPathologySenile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and beta-amyloid deposits in the cerebral cortex and subcortical gray matterLewy bodies in neurons of the cortexEpidemiologyAffects twice as many womenAffects twice as many menInheritanceFamilial in 5–15% casesRarely familialDay-to-day fluctuationSomeProminentShort-term memoryLost early in the diseaseLess affectedDeficits in alertness and attention more than in memory acquisitionParkinsonian symptomsVery rare, occurring late in the diseaseNormal gaitProminent, obvious early in the diseaseAxial rigidity and unstable gaitAutonomic dysfunctionRareCommonHallucinationsOccur in about 20% of patients, usually when disease is moderately advancedOccur in about 80%, usually when disease is earlyMost commonly, visualAdverse effects with antipsychoticsCommonPossible worsening of symptoms of dementiaCommonAcute worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms, which may be severe or life threateningDiagnosis referencesPrognosisAlthough progression rate varies, cognitive decline is inevitable. Average survival from time of diagnosis is 7 yr, although this figure is debated. Average survival from the time patients can no longer walk is about 6 mo.TreatmentGenerally similar to that of other dementiasPossibly cholinesterase inhibitors and memantineSafety and supportive measures are the same as that of all dementias. For example, the environment should be bright, cheerful, and familiar, and it should be designed to reinforce orientation (eg, placement of large clocks and calendars in the room). Measures to ensure patient safety (eg, signal monitoring systems for patients who wander) should be implemented.Providing help for caregivers, who may experience substantial stress, is also important. Nurses and social workers can teach caregivers how to best meet the patient’s needs. Health care practitioners should watch for early symptoms of caregiver stress and burnout and, when needed, suggest support services.Drugs to treat Alzheimer diseaseCholinesterase inhibitors modestly improve cognitive function and memory in some patients. Four are available. Generally, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine are equally effective, but tacrine is rarely used because of its hepatotoxicity.Donepezil is a first-line drug because it has once/day dosing and is well-tolerated. The recommended dose is 5 mg po once/day for 4 to 6 wk, then increased to 10 mg once/day. Donepezil 23 mg once/day dose may be more effective than the traditional 10 mg once/day dose for moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Treatment should be continued if functional improvement is apparent after several months, but otherwise it should be stopped. The most common adverse effects are GI (eg, nausea, diarrhea). Rarely, dizziness and cardiac arrhythmias occur. Adverse effects can be minimized by increasing the dose gradually (see Table: Drugs for Alzheimer Disease).Memantine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, appears to improve cognition and functional capacity of patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. The dose is 5 mg po once/day, which is increased to 10 mg po bid over about 4 wk. For patients with renal insufficiency, the dose should be reduced or the drug should be avoided. Memantine can be used with a cholinesterase inhibitor.Efficacy of high-dose vitamin E (1000 IU po once/day or bid), selegiline, NSAIDs, Ginkgo biloba extracts, and statins is unclear. Estrogen therapy does not appear useful in prevention or treatment and may be harmful. Clinical trials with investigational drugs that target beta-amyloid peptide accumulation and clearance have not been successful although some studies are still ongoing.Drugs for Alzheimer DiseaseDrug NameStarting DoseMaximum DoseCommentsDonepezil5 mg po once/day23 mg once/day (for moderate to severe Alzheimer disease)Generally well-tolerated but can cause nausea or diarrheaGalantamine4 mg po bidExtended-release: 8 mg once/day in the am12 mg bidExtended-release: 24 mg once/day in the amPossibly more beneficial for behavioral symptoms than other drugsModulates nicotinic receptors and appears to stimulate release of acetylcholine and enhances its effectMemantine5 mg po bid10 mg bidUsed in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer diseaseRivastigmineLiquid or capsule: 1.5 mg bidPatch: 4.6 mg/24 hLiquid or capsule: 6 mg bidPatch: 13.3 mg/24 hAvailable in liquid solution and a patchPreventionPreliminary, observational evidence suggests that risk of Alzheimer disease may be decreased by the following:Continuing to do challenging mental activities (eg, learning new skills, doing crossword puzzles) well into old ageExercisingControlling hypertensionLowering cholesterol levelsConsuming a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fatsDrinking alcohol in modest amountsHowever, there is no convincing evidence that people who do not drink alcohol should start drinking to prevent Alzheimer disease.Key PointsAlthough genetic factors can be involved, most cases of Alzheimer disease are sporadic, with risk predicted best by patient age.Differentiating Alzheimer disease from other causes of dementia (eg, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia) can be difficult but is often best done using clinical criteria, which are 85% accurate in establishing the diagnosis.Treat Alzheimer disease similarly to other dementias.More InformationLast full review/revision March 2018 by Juebin Huang, MD, PhDResources In This ArticleDrugs Mentioned In This ArticleDelirium and DementiaOverview of Delirium and DementiaDeliriumDementiaAlzheimer DiseaseBehavioral and Psychologic Symptoms of DementiaChronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)HIV-Associated DementiaLewy Body Dementia and Parkinson Disease DementiaNormal–Pressure HydrocephalusVascular DementiaDementiaBehavioral and Psychologic Symptoms of DementiaTap to switch to the Consumer VersionAlso of InterestMManualTEST YOURKnowledgeThe use of cerebral catheter angiography has dramatically decreased with the advent of which of the following?CT angiographyDuplex Doppler ultrasonographyEchoencephalographyMyelographyAM I CORRECT?Latest NewsFDA OKs Nucala for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With PolyangiitisNEWSHealthDayFDA OKs Nucala for Eosinophilic...Atherosclerosis ID'd in Many Without CV Risk FactorsNEWSHealthDayAtherosclerosis ID'd in Many Without CV...Disrupted Sleep Linked to Increased Amyloid-β ProductionNEWSHealthDayDisrupted Sleep Linked to Increased...Alternative Diagnosis for Many Referred for Optic NeuritisNEWSHealthDayAlternative Diagnosis for Many Referred...15 Million Americans Expected to Have Alzheimer's by 2060NEWSHealthDay15 Million Americans Expected to Have...More News Overview of Alzheimer DiseaseOverview of Alzheimer DiseaseOverview of Alzheimer DiseaseMore Videos STUDENTSTORIESA MEDICAL EDUCATION BLOG My Newfound ObsessionAshleighMy Newfound ObsessionThroughout my life, I have always had a job. Since I was 16, I was working somewhere part-time and earning my own money (even if it was minimum wage)...Creating a Study Space on a BudgetKimiaCreating a Study Space on a BudgetI’ve been moving to a new place and hadn’t had much time or wifi to post. But now that things are starting to settle I thought I’d share my favorite room...More Student StoriesPreviousNext123456MManualMerck and the Merck ManualsMerck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA is a global healthcare leader working to help the world be well. From developing new therapies that treat and prevent disease to helping people in need, we are committed to improving health and well-being around the world. The Merck Manual was first published in 1899 as a service to the community. The legacy of this great resource continues as the Merck Manual in the US and Canada and the MSD Manual outside of North America. Learn more about our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.MERCKMANUALSABOUTDISCLAIMERPERMISSIONSPRIVACYCONTRIBUTORSTERMS OF USELICENSINGCONTACT USGLOBAL MEDICAL KNOWLEDGEVETERINARY EDITION© 2019 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA TRUSTe European Safe Harbor certification Validate TRUSTe privacy certification

|

|

|

|

What |

Dementia should not be confused with delirium, although cognition is disordered in both. The following helps distinguish them: Dementia affects mainly memory, is typically caused by anatomic changes in the brain, has slower onset, and is generally irreversible. Delirium affects mainly attention, is typically caused by acute illness or drug toxicity (sometimes life threatening), and is often reversible.Other specific characteristics also help distinguish the 2 disorders |

|