![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

20 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

Surveillance questions |

• Is surveillance part of a top-down responsibilising neo-liberal project of control, or a positive bottom-up response to growing insecurity? • Potentially empowering? • Context of what seems to be an unstoppable wave of crime, producing more support for more punitive approaches • Desire for revenge on those making our lives a misery, and on those who seem to be having too good a time in their offending |

|

|

Norris, McCahill and Wood, (2004) ‘The growth of CCTV – a global perspective’, Germain et al, (2013) ‘A prosperous business’, |

• CCTV first used in UK for traffic management in late 1950s • By 1970s, CCTV used to monitor football hooligans and political demonstrations • Monitoring of risky populations, not known offenders |

|

|

Big bang of CCTV |

• Late 80s, early 90s • 1984 – Brighton bombing of Tory party conference hotel • 1993 – James Bulger case provoked explosion of demand for more CCTV • Lowering costs of technology • Huge gov’t funding of CCTV installations in public spaces • £4.5bn spent on CCTV in UK, 1995-2004 • Very little regulation, discussion or public opposition to this trend • Increasing partnership of gov’t with commercial sector |

|

|

The global diffusion of CCTV |

• Four-stage development of CCTV: • Private sector, e.g. banks, shopping malls • Diffusion into institutions – schools, hospitals • More limited diffusion into public space • Move towards ubiquity – everywhere assumed to be monitored • Much more debate about this in other European countries – more concern over issues of privacy and liberty • Very uneven spread of CCTV • UK has far more CCTV than anywhere else in Europe • Change not driven by availability of technology, but by demand • By 2003, UK had 40,000 open street cameras • Only 1000 in all other European countries – astonishing disparity • UK’s uncritical embrace of culture of control |

|

|

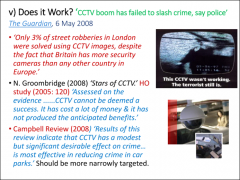

Does CCTV work? |

• Groombridge, ‘Stars of CCTV’, 2005 – CCTV has been expensive and ineffective • Massive investment in CCTV has failed to prevent crime in the UK • Only 3% of street robberies solved with CCTV • Campbell Report, 2008 – CCTV most effective in car parks, should be more targeted • What are CCTV systems really for? • How good are they at crime reduction? • CCTV as a populist, symbolic message, a ‘friendly eye in the sky’ • Garland, 2001 – offers us comfort after disappointment of other crime reduction strategies |

|

|

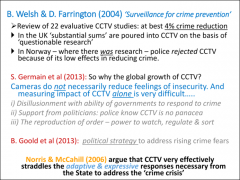

Welsh and Farrington, ‘Surveillance for crime prevention’, 2004 |

• Maybe 4% reduction at best •CCTV not efficient in dealing with crime •No real assessment in UK of impact, large sums spent merely because of public demand •Norwegian police rejected CCTV because of lack of evidence of efficacy, more concern about invasion of privacy

•Assessing effectiveness of CCTV is difficult

|

|

|

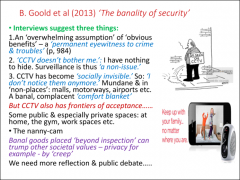

CCTV for everyone: Goold et al, 2013 |

•Goold et al, ‘The banality of security’, 2013 – CCTV may be more about a political gesture to allay public fears than an effective crime prevention measure •About the reproduction of control and ordering of public space •CCTV straddles two key functions of state •Both a adaptive and an expressive response to crime crisis •CCTV not really about reducing crime, more about addressing our anxieties about crime

– interviews identified three popular responses: •Overwhelming assumption of obvious benefits of CCTV •Surveillance seen as a non-issue – ‘nothing to worry about if you have nothing to hide'

•CCTV has become socially invisible – seen as mundane and uncontroversial |

|

|

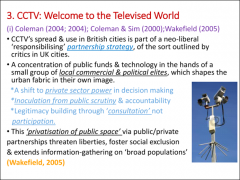

CCTV: welcome to the televised world |

• Coleman, 2004; Coleman and Sim, 2000; Wakefield, 2005 • CCTV as part of a neo-liberal responsibilising partnership strategy • Concentration of power, funds and technology in the service of local commercial and political elites • Marginal interest in reducing crime • More about shaping the urban fabric and public spaces in their own image • Who is eligible to use these spaces, and who should be excluded? • Producing a theme park-like, risk-free, deviance-free public space – spectacle cities, but safe cities • Unaccountable power • Shift to private sector decision makers • Lack of debate, participation, public scrutiny or accountability • Privatisation of public space producing social exclusion |

|

|

CCTV and the ‘landscape of denial’

Coleman, ‘Images from a neo-liberal city’, 2003 |

•Categorising and classifying the users of public spaces – a policing of culture in pursuit of a new urban aesthetic • Commercialisation and commodification of urban space • Increasing criminalisation of deviancy, of users perceived to be inappropriate • Evading discussion about important issues of inequality and inclusion • ‘Joyless pleasure’ – ‘riskless risk’, lack of spontaneity, denying local cultural expression, hostility to social mixing • A marketed and branded version of the city • Dealing with aesthetics more than crime • Emphasis on spectacle and consumption • Systems sold to us on basis of crime reduction, but harnessed to commercial interests |

|

|

CCTV and the homeless |

• Huey, ‘False security or grater social inclusion?’, 2010 • Does CCTV give homeless people protection or lead to greater harassment? • Differing views exist |

|

|

CCTV: beyond penal modernism |

• Norris and McCahill, ‘CCTV: beyond penal modernism’, 2006 • ‘New penology’ based not on observation and monitoring of identified individuals, but rather on universal surveillance • Pre-emptive concerns • Groups classified by levels of dangerousness • Simon, 1994 |

|

|

Proactive exclusion: findings (a) |

• Proactive exclusion as a key feature of control strategies • Move away from formal legal regulation to ‘privatised, unaccountable justice |

|

|

Proactive exclusion: findings (b) |

• Blurring of private and public policing • ‘Hybrid policing’ – diffusion of control to diverse agencies • Co-option of private systems for policing • A rolling out rather than a rolling back of the state |

|

|

Critique of culture of control thesis |

• New culture of control is not complete or efficient, despite Garland’s assertions • Profit-driven organisations cut costs, recruiting poorly-paid and poorly-trained staff • Monitoring cameras is a boring task, and people are badly motivated to do it effectively • Postmodern technologies, but used through modern eyes – focus on familiar suspects |

|

|

Growth of digital surveillance |

• Graham and Wood, ‘Digitalising surveillance’, 2003 • Removes human subjectivity, although computers have to be told what to look for • Interconnection of surveillance systems – movement of data • Allows for the tracking and sorting of populations on a real-time basis • Surveillance creep ensures the integration of data sets, presented as inevitable • We know little about how our personal data is transferred and shared between organisations• |

|

|

Multiple ‘digital selves’ (a) |

• Creation of subjects through databases • When you’re put on hold in a phone queue, the system is often deciding how important a customer you are, and thus how long you should spend in the queue • Norms of behaviour are automatically policed by software • Normative notions embedded in software codes • Are you an appropriate user? • Will you be granted access? |

|

|

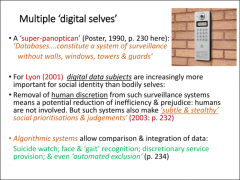

Multiple ‘digital selves’ (b) |

• Lyon, 2001 • Digital data subjects increasingly important for social ID |

|

|

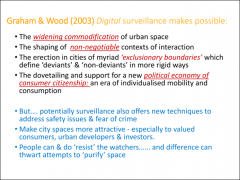

Widening commodification of public space |

• Graham and Wood, ‘Digitalising surveillance: categorisation, space, inequality’, 2003 • New model of consumer citizenship, individualised mobility and consumption • It’s possible to turn the tables, to ‘watch the watchers’, to respond and reject the culture of control |

|

|

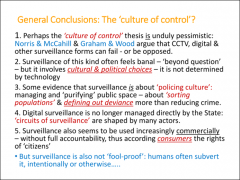

General conclusions on the culture of control |

|

|

|

Rose, ‘Government and control’, 2000 |

• Securitisation of identity • Monitored patterns of credit rating, consumption, access • Surveillance designed into the fabric of everyday life • No ‘Big Brother’, or centralised agency of control • Control widely dispersed and often disorganised • Tangential involvement of the state • Profoundly shaping late-modern citizenship • Circuits of inclusion and exclusion, in both real and online world • Surveillance feels banal because ubiquitous, but has been chosen – not inevitable • Used for policing culture • Increasing commercialisation of citizen |