![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

21 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

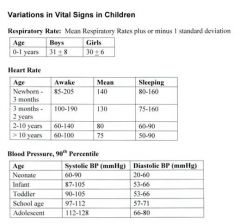

Vital signs in children:

|

|

|

|

Clues to location of the vomitus:

|

Undigested food: Esophageal or gastric origin

Digested food: Gastroduodenal origin Bile: Postampullary origin Blood: Above the ligament of Treitz Feculent: Bacterial overgrowth, colon, necrotic bowel |

|

|

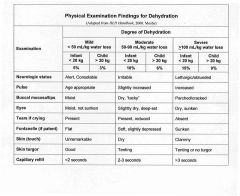

signs of dehydration in an infant:

|

decreased activity level, decreased urine output and increased thirst (in children old enough to indicate thirst). Signs may include tachycardia, tachypnea (if associated with acidosis) weight loss, decreased production of tears, tacky or “dry” mucous membranes, sunken fontanelle and delayed capillary refill. Hypotension and loss of skin turgor (e.g., skin tenting) may be seen with severe dehydration

|

|

|

Degrees to dehydration and clinical findings:

|

|

|

|

Hypetrophic Pyloric Stenosis: Epidemiology

|

affects 1 in 3,000 individuals, with a male:female ratio of 4:1. It is the most common reason for an abdominal operation in the first 6 months of life. It is more common in northern Europeans, less common in African-Americans and very rare in Asians. The disorder tends to aggregate in families, particularly in the children of an affected mother. There is a higher incidence in infants with blood groups O or B.

|

|

|

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: Clinical Presentation

|

Normally the vomiting starts at 3-4 weeks of age, but symptoms may develop as early as 1 week of age and as late as 3 months; it is almost never symptomatic in the newborn nursery. The vomiting may have variable force, but is classically described as projectile. Vomiting may initially be delayed after feedings, but eventually occurs immediately after feedings as the pylorus becomes progressively more obstructed. Vomitus is nonbilious. Fever and diarrhea are absent. Appetite is initially preserved, though severely dehydrated patients may develop lethargy and decreased feeding. On physical exam the diagnosis has traditionally been established by palpating the pyloric mass (firm, mobile, 2 cm, olive shaped, in the midepigastrium above and to the right of the umbilicus); it is easier to palpate after vomiting when the musculature is more relaxed. In some cases jaundice may be associated with pyloric stenosis. The examiner may visualize gastric peristalsis after feeding.

Infants with pyloric stenosis may also have significant electrolyte abnormalities associated with continuous vomiting. Most commonly this presents as hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, due to the loss of hydrochloric acid in the vomitus. The sodium is often low as well, while potassium is usually normal |

|

|

When should electrolytes be measured in children with suspected dehydration?

|

(1) Children with moderate to severe dehydration; (2) Dehydrated children whose history and physical findings are inconsistent with a straightforward diarrheal episode; and (3) Children at risk for hyponatremia or hypernatremia.

|

|

|

hypernatremia and potential causes:

|

most commonly occurs when water intake is reduced in the face of excessive water loss (from vomiting or diarrhea). Hypernatremia also develops when there is ingestion of hypertonic fluids (boiled milk, home-made solutions to which salt is added, improperly mixed formula or significantly inadequate breast milk supply).

|

|

|

Treatment for hypernatremia

|

slow replacement of fluids. Serum sodium should be lowered slowly, not more than 1meq/2hr (10meq/24hr).

|

|

|

development of hyponatremia

|

ingestion of hypotonic fluids, such as fluids without salt (including free water) and improperly mixed formula.

|

|

|

What are the most common electrolyte abnormalities in pyloric stenosis?

|

hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, due to the loss of hydrochloric acid in the vomitus. The sodium and potassium are usually normal.

|

|

|

What is the most common cause of gastroenteritis in infants?

|

Rotavirus

|

|

|

Features of Rotavirus:

|

affects almost all children by age 5 years. Rotavirus spreads efficiently via a fecal-oral route. Outbreaks are common in children's daycare centers. The incubation period is approximately 48 hours. It selectively infects and destroys villus tip cells in the small intestine (duodenum).

|

|

|

Diagnosis and Treatment of Rotavirus:

|

The diagnostic test is rotavirus antigens in feces, done by two methods: enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or latex agglutination (LA). EIA has 95-100% sensitivity and specificity. LA is much faster, but is less sensitive and specific. Tx is rehydrate

|

|

|

Prevention of Rotavirus:

|

RotaTeq: After completion of three doses, the efficacy of the vaccine against severe gastroenteritis is 98%; against any severity, efficacy is 74%. Vaccination early in life mimics a child's first natural infection and may prevent severe cases of rotavirus disease and sequelae (e.g., dehydration, physician visits, hospitalization, and death). A three-dose series is recommended to be administered at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months of age. The vaccine's side effects include a slightly increased incidence of mild, self-limited vomiting and diarrhea within 7 days after vaccination.

|

|

|

Calculating Fluid Therapy in Children: 4 Steps:

|

1. Support cardiovascular circulation 2. Correct dehydration 3. Provide maintenance fluids 4. Replace any ongoing losses

|

|

|

1. Support cardiovascular circulation

|

in otherwise healthy patients with moderate or severe dehydration, who have evidence of diminished urine output or impaired cardiac output (as evidenced by tachycardia), an IV fluid bolus of 20 mL/kg of normal saline (without dextrose) is given over 20 minutes to one hour. The bolus is repeated until the patient has urinated and the tachycardia has improved. The bolus is in addition to the fluids described below. Caution should be taken in patients with evidence of increased ICP, renal failure or cardiac failure.

|

|

|

2. Correct dehydration

|

The next step is to calculate and replace the patient's current fluid deficit. To do so, multiply the patient's weight in grams (remembering that grams and milliliters are interchangeable) by the estimated percent dehydration. In cases of mild-moderate dehydration, the deficit should be replaced over the next 24 hours: half of the deficit should be replaced over the first 8 hours and the second half of the deficit over the final 16 hours. If you choose to use the oral route, you need to give the fluids very slowly to prevent further vomiting, giving no more than 5 to 10 mL every 1-5 minutes. You may increase the amount as tolerated to meet the replacement need.

If you choose to use the IV route, use a solution of D5 1/4 normal saline. A solution of D5 1/2 normal saline may be used for patients >10kg. Once the child is voiding, 20 mEq/L of KCl should be added to the IV fluids. |

|

|

What should be done for kids with hypernatremia?

|

Patients with suspected or known hypernatremia (Na >150) should have their deficit replaced evenly over 48 hours, taking care not to drop the sodium faster than 1mEq/2hrs. The deficit can be replaced with either IV or oral rehydration solutions.

|

|

|

3. Provide maintenance fluids

|

For infants <10kg, daily maintenance fluids needs are calculated at 100 mL/kg/d. This can be delivered with either IV or oral rehydration solutions, or with full-strength formula or breast milk. Daily maintenance needs are given in addition to the bolus and deficit fluids calculated above.

|

|

|

Maintenance fluid calculations for children of different sizes:

|

0-10 kg: 100 mL/kg per day

10-20 kg: 1000 mL (+ 50 mL/kg for each >10 kg) per day >20 kg: 1500 mL (+ 20 mL/kg for each >20 kg) per day |