![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

41 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

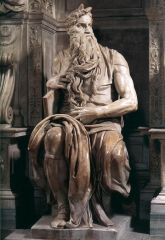

Michelangelo

Moses c. 1513-15 S. Pietro in Vincoli, Rome |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Michelangelo

Piazza Campidoglio "During the last 30 years of Michelangelo's life, his main pursuit was architecture." -Janson designed c. 1545 Rome |

a/t********/d/l

|

|

|

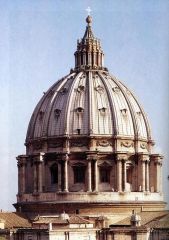

Michelangelo

Basilica of St. Peter begun in 1546 (dome completed by Giacomo della Porta, 1590) Rome |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Bacchanal (On the island of Andros) c.1518 Museo del Prado, Madrid This was the last in a series of magnificent paintings painted by Titian for Alfonso d'Este, Duke of Ferrara: another, also in the Prado, was the Worship of Venus; a third, Bacchus and Ariadne, is in the National Gallery, London. The subjects are taken from classical descriptions of works of art: here Titian reproduces a picture the writer Philostratus saw in Naples in the second century AD, representing the people of the Greek Island of Andros making merry on the river of wine that Dionysus had created. This splendid opportunity to emulate the past was not lost on Titian, whose brilliant naturalism and marvellous colour declare him the equal of Apelles. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Pesaro Altarpiece 1519-26 Pesaro Chapel, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice Titian was neither such a universal scholar as Leonardo, nor such an outstanding personality as Michelangelo, nor such a versatile and attractive man as Raphael. He was principally a painter, but a painter whose handling of paint equalled Michelangelo's mastery of draughtsmanship. This supreme skill enabled him to disregard all the time-honoured rules of composition, and to rely on colour to restore the unity which he apparently broke up. We need but look at Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family which was begun only some fifteen years after Giovanni Bellini's Madonna with saints to realize the effect which his art must have had on contemporaries. It was almost unheard of to move the Holy Virgin out of the centre of the picture, and to place the two administering saints - St Francis, who is recognizable by the Stigmata (the wounds of the Cross), and St Peter, who has deposited the key (emblem of his dignity) on the steps of the Virgin's throne - not symmetrically on each side, as Giovanni Bellini had done, but as active participants of a scene. In this altar-painting, Titian had to revive the tradition of donors' portraits, but did it in an entirely novel way. The picture was intended as a token of thanksgiving for a victory over the Turks by the Venetian nobleman Jacopo Pesaro, and Titian portrayed him kneeling before the Virgin while an armoured standard-bearer drags a Turkish prisoner behind him. St Peter and the Virgin look down on him benignly while St Francis, on the other side, draws the attention of the Christ Child to the other members of the Pesaro family, who are kneeling in the corner of the picture. The whole scene seems to take place in an open courtyard, with two giant columns which rise into the clouds where two little angels are playfully engaged in raising the Cross. Titian's contemporaries may well have been amazed at the audacity with which he had dared to upset the old-established rules of composition. They must have expected, at first, to find such a picture lopsided and unbalanced. Actually it is the opposite. The unexpected composition only serves to make it gay and lively without upsetting the harmony of it all. The main reason is the way in which Titian contrived to let light, air and colours unify the scene. The idea of making a mere flag counterbalance the figure of the Holy Virgin would probably have shocked an earlier generation, but this flag, in its rich, warm colour, is such a stupendous piece of painting that the venture was a complete success." |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Raphael

Baldassare Castiglione c. 1514 Commissioned by Castiglione (Louvre) The Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione, a literary figure active at the court of Urbino in the early years of the 16th century, may or may not have been painted by Raphael. According to a letter of 1516 from Pietro Bembo to Cardinal Bibbiena, "The Portrait of M. Baldassar Castiglione... [and that of Duke Guidobaldo di Montefeltro] would seem to be by the hand of one of Raphael's pupils". But the high quality and masterful combination of pictorial elements which distinguish the painting (note the affection inherent in the intelligent and calm face of Castiglione) lead one to believe that the master participated in some way in its execution. Certainly the shaded tonalities of the clothing and the unusually light background indicate the hand of a skillful and experienced painter. Baldassare Castiglione, a humanist and a writer, was one of the most important men of the Italian Renaissance. His popular book "Il cortegiano" (The Courtier) summed up the tastes and culture of the Renaissance, it gives insights into the thinking and culture at the court of Urbino at the turn of the 16th century, and is written in a style that is delightfully clear and precise. Rubens admired Raphael's portrait of Castiglione so much that he copied it. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

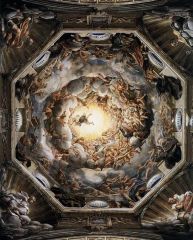

Correggio

The Assumption of the Virgin c. 1525 Duomo, Parma The fresco of the Assumption of the Virgin in the dome of the cathedral of Parma marks the culmination of Correggio's career as a mural painter. This fresco (a painting in plaster with water-soluble pigments) anticipates the Baroque style of dramatically illusionistic ceiling painting. The entire architectural surface is treated as a single pictorial unit of vast proportions, equating the dome of the church with the vault of heaven. The realistic way the figures in the clouds seem to protrude into the spectators' space is an audacious and astounding use for the time of foreshortening. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Man with the Glove c. 1520 Louvre |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Pope Paul III and His Grandsons 1546 Museo di Capodimonte, Naples According to Vasari this painting was commissioned by the Farnese family in 1546. Titian arrived to Rome in 1545 and he met there several cardinals and artists and he was even received by Pope Paul III. A few decades earlier, Pope Leo X (1475-1521), who was a great patron of Pope Paul III, was also portrayed by Raphael with two of his relatives, his nephews Giulio de' Medici and Luigi de Rossi. Giulio later became Pope Clement VII. The political allusion to this painting is clear in Paul III's decision to be portrayed with two of his younger relatives. In terms of composition, though, Titian is scarcely influenced by Raphael. He finds his own subtle means of expressing the political claims of Paul III. Titian shows the old, stooped pope grasping the armrest with his left hand, and he gives the pontiff a wily expression quite at odds with the conventions of state portraiture. The free movement of the models - quite unusual in contemporary portrait paintings - contributes to the extraordinary qualities of this group portrait. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Danae (DAN-ee) (Mother by Zeus of Perseus, who killed the Medusa and rescued Andromeda from the sea monster) c. 1544-46 Museo di Capodimonte,Naples It was through Aretino in 1539 that Titian first offered his services to the family of the Farnese Pope Paul III. After painting the Pope's grandson Ranuccio in 1542, Titian's next commission for the family was a Danaë seduced by Jupiter in the guise of a shower of gold coin. He began the canvas in Venice in 1544 for Ranuccio's elder brother, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, and when he left for Rome the following year, he took it with him to finish. Giorgio Vasari, the biographer and protege of Michelangelo, brought the Master to see it. The latter was full of compliments in Titian's presence, but according to Vasari later complained that, though he liked the colouring and style, "it was a pity that in Venice they never learned to draw and that their painters did not have a better method of study." The pose is obviously Michelangelesque while the cupid is based on a statue in the style of Lysippus, which Titian would have known since it was already in Venice in the collection of Cardinal Grimani. X-rays reveal an underlying composition close to the Venus of Urbino, but as a papal legate remarked to Cardinal Alessandro, the erotic Danaë made the Venus of Urbino look like "a Theatine nun". The model was reputedly the Cardinal's mistress, a courtesan named Angela. |

a/t*********/d/l

|

|

|

Parmigianino

Gian Galeazzo Sanvitale, Count of Fontanellato (near Parma) 1524 Pinacoteca, Museo Nazionale, Naples |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Parmigianino

Madonna of the Long Neck begun 1534, left unfinished in 1540 Baiardi Chapel, Santa Maria dei Servi, Parma (Uffizi) |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Empress Isabel of Portugal (wife of Charles V) 1548 Museo del Prado, Madrid |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

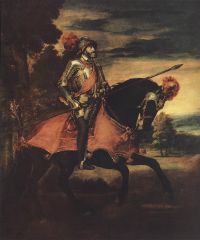

Titian

Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg 1548 Museo del Prado, Madrid This is one of Titian's most dramatic and monumental portraits, conveying not so much the personality of the sitter as the high ideals of his imperial office. At the Battle of Mühlberg the Emperor had defeated the Schmalkadic League of Protestant princes, and in Titian's picture he is portrayed as the archtypal Christian knight victorious against heresy - a kind of modern St George. Apart from the brilliant creaton of a memorable image, Titan shows his skill in the consummate handling of textures, such as the diffusion of the evening sunlight through the landscape and the captivating sheen of the armour. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Titian

Christ Crowned with Thorns c. 1570 Alte Pinakothek, Munich In his final years Titian painted a series of paintings dedicated to the passion of Christ. These works, which include the Crowning with Thorns, are pervaded with immense dramatic power, the brushstrokes gradually dissolve into rapidly applied dabs of pigment. The aim is no longer to reproduce nature but to directly convey the raw emotion of the painter, who is participating fully in the tragic subject of his picture. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Correggio

Jupiter and Io early 1530s Vienna, commissioned by Federigo Gonzaga Two vertical canvases depicting Io and Ganymede, datable to 1531-32, are now in Vienna. These were made for Federigo Gonzaga, first duke of Mantua. The duke intended to line a room in his palace with the Loves of Jupiter. Jupiter was a mythical ancestor of the Gonzaga family and, in his amorous exploits, not unlike Federigo. |

a/t/d/l/ commissioned by

|

|

|

Correggio

Ganymede early 1530s Vienna |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Agnolo Bronzino

Allegory of Venus c. 1546 National Gallery, London. Commissioned by Cosimo I as a gift to Francis I of France "High Mannerism is identified with the second generation of Mannerists. They transformed the styles of Rosso, Pontormo, and Parmigianino into one of cool perfection that filtered out the highly personal sensibilities of those artists. As a result they produced few masterpieces. In their best works, however, formal beauty becomes the esthetic counterpart of esoteric thought. |

a/t/d/l/ commissioned by

|

|

|

Agnolo Bronzino

Cosimo I de' Medici in Armour c. 1545 Uffizi |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Agnolo Bronzino

Eleonora of Toledo with her son Giovanni de' Medici c. 1545 Uffizi |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Jacopo SansOVino

St. James 1511-1518 Duomo, Florence |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Jacopo SanSOvino

Mint (Left) and library of St. Mark's (Biblioteca Marciana) begun c. 1537 Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Giulio Romano

Palazzo del Te 1527-34 Mantua |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Bartolommeo Ammanati

Courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti 1558-70 Florence |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

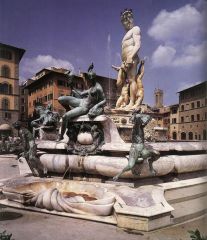

Bartolommeo Ammanati

Fountain of Neptune 1559-75 Piazza della Signoria, Florence Since 1550 there was a rivalry between Bandinelli, Cellini and Ammanati to make a fountain in the Piazza della Signoria. After Bandinelli's death in 1560 Cellini and Ammanati both sought the commission, which Michelangelo and Vasari ultimately secured for Ammanati, an experienced carver. In 1565 Ammanati's model for the giant was set up for the wedding of Francesco de' Medici and Giovanna d'Austria, although the marble was only completed in 1570 and the fountain unveiled in 1575. Ammanati's Neptune stands on a sea-shell chariot, pulled by four horses rising out of the water, and carries a general baton. Neptune is presented as a civic protector, alluding to Cosimo's efforts to increase the water supply and to establish a viable port at Livorno. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Benvenuto Cellini

Saltcellar of Francis I 1539-43 Vienna |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Benvenuto Cellini

Perseus 1545-1554 commissioned by Cosimo I for the Loggia della Signoria The sculpture shows Perseus, holding the head of the Medusa which he has cut off and from whose blood the winged horse Pegasus will be born. This masterpiece in bronze was sculpted between 1545 and 1554 for the Loggia dei Lanzi (an open-air gallery) and has stood there ever since. The sculpture can be considered as the result of a direct competition with Donatello's earlier sculpture, Judith and Holophernes. The modelling of the reliefs in bronze on the marble base is so exquisitely done that it suggests the precision of the goldsmith rather than the sculptor's art. |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Giorgio Vasari

Loggia of the Palazzo degli Uffizi begun 1560 Florence |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Andrea Palladio

Villa Rotonda c. 1567-70 Vicenza |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Andrea Palladio

S. Giorgio Maggiore designed 1565 Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Giorgio Vasari

Perseus and Andromeda 1570-72 Palazzo Vecchio, Florence |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Jacopo Tintoretto

Christ Before Pilate c. 1566-67 Scuola di San Rocco, Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Jacopo Tintoretto

Ariadne, Venus and Bacchus (on the Isle of Naxos, where Ariadne has been abandoned by Theseus after giving him the ball of thread to aid in his plight against the Minotaur) 1576 Sala di Anticollegio, Palazzo Ducale, Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Jacopo Tintoretto

The Last Supper 1592-94 S. Giorgio Maggiore, Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

El Greco

The Agony in the Garden 1597-1600 The Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

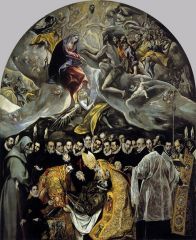

El Greco

Burial of Count Orgaz 1586 Toledo, Spain |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Paolo Veronese

Christ in the House of Levi 1573 Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Paolo Veronese

Mars and Venus United by Love 1570 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna)

Rape of the Sabines 1581-83 Loggia dei Lanzi The Rape of the Sabines marked the climax of Giambologna's career as an official Medici sculptor. This great marble was unveiled in the Loggia dei Lanzi in January 1583 in place of Donatello's Judith. The group is indebted to Giambologna's study of Hellenistic sculpture, particularly in the voids which penetrate the three interlocked figures. On a technical level it represents the fullfilment of an aspiration from antiquity. Ancient sources record sculptures made from a single block, a claim which the Renaissance discovered was not true. Giambologna intended to surpass antiquity by sculpting a large group from a single block that also involved a complicated lift. The result is the first sculpture with no principal viewpoints, it forms a spiral that is the culmination of the "figura serpentina". |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

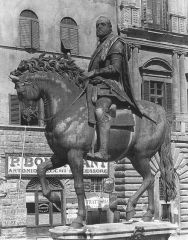

Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna)

Equestrian Monument to Cosimo I 1587-95 Piazza della Signoria, Florence |

a/t/d/l

|

|

|

Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna)

Hercules and the Centaur 1600 Loggia dei Lanzi |

a/t/d/l

|