![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

26 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

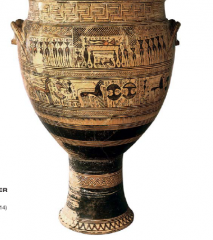

Vase from Dipylon Cemetery, Athens c 750 BCE

|

|

|

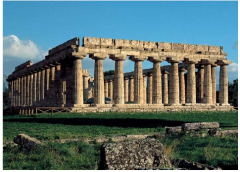

Temple of Hera I, Paestum, Italy c 550 BCe

A particularly well-preserved Archaic Doric temple, at the former Greek colony of Poseidonia. Dedicated to Hera, the wife of Zeus.A row of columns called the peristyle surrounded the main room, the cella. The columns of Hera I are especially robust only about four times as high as their maximum diameter and topped with a widely flaring capital and a broad, blocky abacus, creating an impression of great stability and permanence. As the column shafts rise, they swell in the middle and contract again toward the top, giving them a sense of energy and lift. Hera I has nine—across the short ends of the peristyle, with a column instead of a space at the center of the two ends. The entrance to the enclosed vestibule has three columns in between flanking wall piers, and a row of columns runs down the center of the wide cella to help support the ceiling and roof. The unusual two-aisle, two-door arrangement suggest two presiding deities. |

|

|

l

|

|

|

l

|

|

|

l

|

|

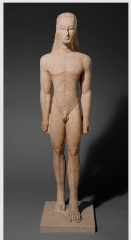

Kouros Figure c 580 BCE

In addition to statues designed for temple exteriors, sculptors of the Archaic period created a new type of large, free-standing statue made of wood, terra cotta, limestone, or white marble.These free-standing figures were brightly painted and sometimes bore inscriptions indicating that individual men or women had commissioned them for a commemorative purpose. They have been found marking graves and in sanctuaries, where they lined the sacred way from the entrance to the main temple.Kouroi ,nearly always nude, have been variously identified as gods, war-riors, and victorious athletes. Because the Greeks associated young, athletic males with fertility and family continuity, the kouros figures may have symbolized ancestors. This recalls the pose and proportions of Egyptian sculpture of Menkaure,this young Greek stands rigidly upright, arms at his sides, fists clenched, and one leg slightly in front of the other. However, the Greek artist has cut away all stone |

continued

from around the body to make the human form free-standing. Archaic kouroi are also much less lifelike than their Egyptian forebears. Anatomy is delineated with linear ridges and grooves that form regular, symmetrical patterns. The head is ovoid and schematized, and the wiglike hair evenly knotted into tufts and tied back with a narrow ribbon. The eyes are relatively large and wide open, and the mouth forms a conventional closed-lip expression known as the Archaic smile.In Egyptian sculpture, male figures usually wore clothing associated with their status, such as the headdresses, necklaces, and kilts that identified them as kings. The total nudity of the Greek kouroi is unusual in ancient Mediterranean cultures, but it is acceptable even valued in the case of young men. Not so with women. |

|

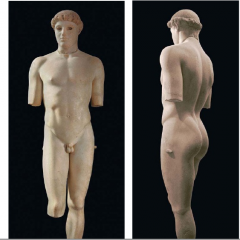

ANAVYSOS KOUROS The powerful, rounded, athletic body of a kouros documents the increasing interest of artists and their patrons in a more lifelike rendering of the human figure The pose, wiglike hair, and Archaic smile echo the earlier style, but the massive torso and limbs have carefully rendered, bulging muscularity, suggesting heroic strength. The statue, a grave monument to a fallen war hero, has been associated with a base inscribed: “Stop and grieve at the tomb of the dead Kroisos, slain by wild Ares [god of war] in the front rank of battle.” However, there is no evidence that the figure was meant to preserve the likeness of Kroisos or anyone else. He is a symbolic type, not a specific individual.

|

Kroisos/Anavysos Kouros c 525 BCE

A female statue of this type is called a kore plural korai..Greek for “young woman,” The kore in though she is a votive rather than a funerary statue. Like the kouros she has rounded body forms, but unlike him, she is clothed. She has the same motionless, vertical pose but her bare arms and head convey a sense of soft flesh covering a real bone structure, and her smile and hair are considerably less stylized. The original painted colors on both body and clothing must have made her seem even more lifelike, and she also once wore a metal crown and jewelry. |

|

|

Standing Youth Kritian Boy c 480 BCE

the Greeks established an ideal of beauty that has endured in the Western world to this day. Scholars have associated Greek Classical art with three general concepts: humanism, rationalism, and idealism The softly rounded body forms, broad facial features, and calm expression give the figure an air of self-confident seriousness. His weight rests on his left, engaged leg, while his right, relaxed leg bends slightly at the knee, and a noticeable curve in his spine counters the slight shifting of his hips and a subtle drop of one of his shoulders. We see here the beginnings of contrapposto, the convention later developed in full by High Classical sculptors such as Polykleitos of presenting standing figures with opposing alterna-tions of tension and relaxation around a central axis. The slight turn of the head invites the spectator to follow his gaze and move around the figure, admiring the small marble statue from every angle. |

|

|

Myron,Diskobolos (discus thrower) 450 BCE

|

|

|

Iktinos and Kallikrates, the Parthenon,

|

|

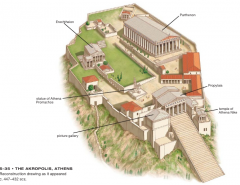

Beginning at entrance (counterclockwise)

1. Temple of Atehna Nike 2.Propylaia 3.Parthenon 4.Erectheion 5.Picture Gallery/museum |

Early /High Classical

Athens Acropolis 447-438 BCE |

|

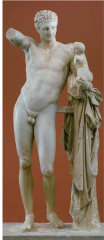

4th Century Classical Art

Praxitleles,Hermes and the Infant Son Dionysus,330 BCE Throughout the fifth century bce, sculptors had accepted and worked within standards for the ideal proportions and forms of the human figure, as established by Pheidias and Polykleitos at mid century. But fourth-century bce artists began to challenge and modify those standards.In particular, a new canon of proportions associated with the sculptor Lysippos emerged for male figures now eight or more “heads” tall rather than the six-and-a-half or seven-head height of earlier works. The calm, noble detachment characteristic of High Classical figures gave way to more sensitively rendered expressions of wistful introspection, dreaminess, even fleeting anxiety or light heartedness.The Late Classical sculptor Praxiteles carved a “Hermes of stone who carries the infant Dionysos” for the Temple of Hera at Olympia. The statue depicting the messenger god Hermes teasing the baby Dionysos with a bunch of grapes. The |

continued

sculpture highlights the differences between the fourth and fifth century bccentury bce Classical styles. Hermes has a smaller head and a more sensual and sinuous body than Polykleitos’ Spear Bear. His off-balance, S-curving pose, requires him to lean on a post a clear contrast with the balanced posture of Polykleitos’ work. Praxiteles also created a sensuous play of contrasting textures over the figure’s surface, juxtaposing the gleam of smooth flesh with crumpled draperies and rough locks of hair. Praxiteles humanizes his subject with a hint of narrative—two gods, one a loving adult and the other a playful child, caught in a moment of absorbed companionship. |

|

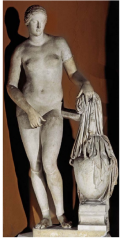

4th Century Classical Art

Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Knidos, 350-340BCE Praxiteles created a daring statue of Aphrodite for the city of Knidos in Asia Minor. Although artists of the fifth century bce had begun to hint boldly at the naked female body beneath tissue-thin drapery as in the panel showing a Nike adjusting her sandal this Aphrodite was apparently the first statue by a well-known Greek sculptor to depict a fully nude woman, and it set a new standard. Although nudity among athletic young men was admired in Greek society, nudity among women was seen as a sign of low character. The acceptance of nudity in statues of Aphrodite may be related to the gradual merging of the Greeks’ concept of this goddess with some of the characteristics of the Phoenician goddess Astarte (the Babylonian Ishtar), who was nearly always shown nude in Near Eastern art.In the version of Praxiteles’ statue the goddess is preparing to take a bath, with a water jug and her discarded clothing at her side. Her |

Her hand is caught in a gesture of modesty that only calls attention to her nudity. Her strong and well toned body leans forward slightly, with one projecting knee in a seductive pose that emphasizes the swelling forms of her thighs and abdomen.

|

|

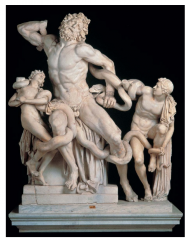

Athanadorus,Hagesandros,Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoon and his Sons, 1stc BCE

|

This kind of deliberate attempt to elicit a specific emotional response in the viewer is known as expressionism, and it was to become a characteristic of Hellenistic art.This complex sculptural composition illustrates an episode from the Trojan War when the priest Laocoön warned the Trojans not to bring within their walls the giant wooden horse left behind by the Greeks. The gods who supported the Greeks retaliated by sending serpents from the sea to destroy Lao-coön and his sons as they walked along the shore. The struggling figures, anguished faces, intricate diagonal movements, and skillful unification of diverse forces in a complex composition all suggest a strong relationship between Rhodian and Pergamene sculptors. Although sculpted in the round, the Laocoön was composed to be seen frontally and from close range, and the three figures resemble the relief sculpture on the altar from Pergamon.

|

|

|

Nike Of Samothrace

THE NIKE OF SAMOTHRACE This winged figure of Victory is even more theatrical than the Laocoön. In its original setting in a hill-side niche high above the theater in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods at Samothrace, perhaps drenched with spray from a fountain this huge goddess must have reminded visitors of the god in Greek plays who descends from heaven to determine the out-come of the drama. The forward momentum of the Nike’s heavy body is balanced by the powerful backward thrust of her enormous wings. The large, open movements of the figure, the strong contrasts of light and dark on the deeply sculpted forms, and the contrasting textures of feathers, fabric, and skin typify the finest Hellenistic art. The wind whipped costume and raised wings of this Nike indicate that the work probably commemorated an important naval victory. |

|

Roman Art

Dionysiac Mystery Frieze, Pompeii 60-50 BCE |

Here a series of elaborate figural murals from the mid first century bce seem to portray the initiation rites of a mystery religion, probably the cult of Bacchus, which were often performed in private homes as well as in special buildings or temples. Perhaps this room in this villa was a shrine or meeting place for such a cult to this god of vegetation, fertility,and wine. Bacchus (or Dionysus) was one of the most important deities in Pompeii.The entirely painted architectural setting consists of a simulated marble dado (similar to that which we saw in the House of the Vettii) and, around the top of the wall, an elegant frieze sup-ported by painted pilaster strips. The figural scenes take place on a shallow “stage” along the top of the dado, with a background of a brilliant, deep red—now known as Pompeian red—that, as we have already seen, was very popular with Roman painters. The tableau unfolds around the entire room, perhaps a succession of events that culminate in the acceptance of

|

|

Roman Art

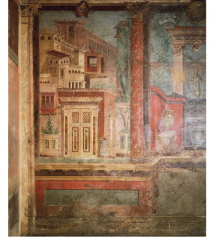

Wall Painting from Villa of Publius Fannus Synistor |

A complex combination of painted fantasies fills the walls of a reception room off the peristyle garden.At the base of the walls is a lavish frieze of simulated colored-marble revetment, imitating the actual stone veneers that are found in some Roman residences. Above this “marble” dado are broad areas of pure red or white, onto which are painted pictures resembling framed panel paintings, swags of floral garlands, or unframed figural vignettes. The framed picture here illustrates a Greek mythological scene from the story of Ixion, who was bound by Zeus to a spinning wheel in punishment for attempting to seduce Hera. Between these pictorial fields, and along a long strip above them that runs around the entire room, are fantastic architec-tural vistas with multicolored columns that recede into fictive space through the use of fan-ciful linear perspective. The fact that this fictive architecture is occupied here and there by volumetric figures enchances the 3d spaital defenition.

|

|

|

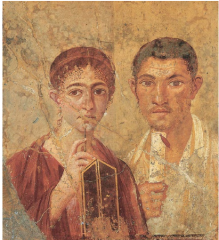

Portrait of Husband and Wife Pompeii 70-79ceThe swarthy, wispy-bearded man addresses us with a direct stare, holding a scroll in his left hand, a conven-tional attribute of educational achievement seen frequently in Roman portraits. Though his wife overlaps him to stake her claim to the foreground, her gaze out at us is less direct. She also holds fashionable attributes of literacy the stylus she elevates in front of her chin and the folding writing tablet on which she would have used the stylus to inscribe words into a wax infill. This picture is comparable to a modern studio portrait photograph perhaps a wedding picture with its careful lighting and retouching, con-ventional poses and accoutrements. But the attention to physiog-nomic detail note the differences in the spacing of their eyes and the shapes of their noses, ears, and lips makes it quite clear that we are in the presence of actual human likenesses.

|

|

Wall Painting in the Ixion Room of the house of the Vetti, Pompeii, 70-79ce

|

The walls of a room from another villa, this one at Boscoreale, farther removed from Pompeii and dating slightly later, open onto a fantastic urban panorama Surfaces seem to dissolve behind an inner frame of columns and lintels, opening onto a maze of complicated architectural forms, like the painted scenic back-drops of a stage. Indeed, the theater may have inspired this kind of decoration, as the theatrical masks hanging from the lintels seem to suggest. By using a kind of intuitive perspective, the artists have created a general impression of real space beyond the wall. Intuitive perspective, the architectural details follow diagonal lines that the eye interprets as parallel lines receding into the distance, and objects meant to be perceived as far away from the surface plane of the wall are shown gradually smaller and smaller than those intended to appear in the foreground.

|

|

Augustus of Primaporta, Early 1st ce

This work demonstrates the creative combination of earlier sculptural traditions that is a hallmark of Augustan art. In its idealization of a specific ruler and his prowess, the sculpture also illustrates the way Roman emperors would continue to use portraiture for propaganda that not only expressed their authority directly, but rooted it in powerfully traditional stories and styles.The sculptor of this larger-than-life marble statue adapted the standard pose of a Roman orator by melding it with the contrapposto and canonical proportions developed by the Greek High Classical sculptor Polykleitos, as exemplified by his Spear Bearer. Like the heroic Greek figure, Augustus’ portrait captures him in the physical prime of youth, far removed from the image of advanced age idealized in the coin portrait of Julius Caesar. Although Augustus lived almost to age 76, in his portraits he is always a vigorous ruler, eternally young. But like Caesar, and unlike |

the Spear Bearer ,Augustus’ face is rendered with the kind of details that make this portrait an easily recognizable likeness.To this combination of Greek and Roman traditions, the sculptor of the Augustus of Primaporta added mythological and historical imagery that exalts Augustus’ family and celebrates his accomplishments. Cupid, son of the goddess Venus, rides a dolphin next to the emperor’s right leg, a reference to the claim of the emperor’s family, the Julians, to descent from the goddess Venus through her human son Aeneas. Augustus’ torso armor is also covered with figural imagery. Mid-torso is a scene representing Augustus’ 20 bce diplomatic victory over the Parthians; a Parthian (on the right) returns a Roman mili-tary standard to a figure variously identified as a Roman soldier the goddess Roma. Looming above this scene at the top of the cui-rass is a celestial deity who holds an arched canopy, implying that the peace signified by the scene below has cosmic implications.

|

|

|

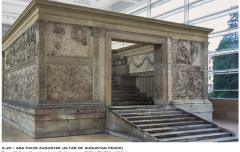

Ara Pacis Augustae (altar of Augustan Peace) Rome, 13-9 BCE

Pax Romana The processional frieze son the exterior sides of the enclosure wall clearly reflect Classical Greek works like the ionic frieze of the Parthenon.With 3-d figured wrapped in revealing drapperies that also create rythmic patterns of rippling folds. Unlike the Greek sculptors of the Parthenon the ara Pacis depicted actual individuals participating in events known. |

|

|

Pont-du-Gard, Nimes, France 70-80 Bce

|

|

Colosseum, Rome 70-80 BCE

|

The curving, outer wall of the Colosseum consists of three levels of arcades surmounted by a wall-like attic (top) story. Each arch is framed by engaged columns. Entablature-like friezes mark the divisions between levels. Each level also uses a different archi-tectural order, increasing in complexity from bottom to top: the plain Tuscan order on the ground level, Ionic on the second level, Corinthian on the third, and Corinthian pilasters on the fourth. The attic story is broken by small, square windows, which origi-nally alternated with gilded-bronze shield-shaped ornaments called cartouches , supported on brackets that are still in place.

|

|

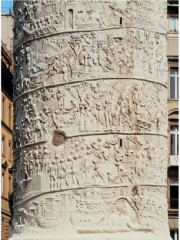

Column of Trajan, Rome 113-116 BCE

The relief decoration on the COLUMN OF TRAJAN spirals upward in a band that would stretch almost 625 feet if laid out straight. Like a giant, unfurled version of the scrolls housed in the libraries next to it, the column presents a continuous pictorial narrative of the Dacian campaigns. The remarkable sculpture includes more than 2,500 individual figures linked by land-scape and architecture, and punctuated by the recurring figure of Trajan. The narrative band slowly expands from about 3 feet in height at the bottom, near the viewer, to 4 feet at the top of the column, where it is farther from view. The natural and architectural elements in the scenes have been kept small so the important figures can occupy as much space as possible. The scene at the beginning of the spiral, at the bottom of the column, shows Trajan’s army crossing the Danube River on a pontoon bridge to launch the first Dacian campaign o |

continued

In this spectacular piece of imperial ideology or propaganda, Trajan is portrayed as a strong, stable, and efficient commander of a well-run army, and his barbarian enemies are shown as worthy opponents of Rome. |

|

|

Arch of Constantine, Rome 312-315 BCE

|

|

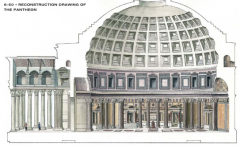

The Romans were pragmatic builders, and their practicality extended from recognizing and exploiting undeveloped potential in construction methods and physical materials to organizing large scale building works. Their exploitation of the arch and the vault is typical of their adapt and improve approach.Today we can see the sides of the rotunda flanking the entrance porch building. pass through the rectilinear and restricted aisles of the portico and the huge main door to encounter the gaping space of the giant rotunda (circular room) surmounted by a vast, bowl-shaped dome, 143 feet in diameter and 143 feet from the floor at its summit.Standing at the center of this hemispherical temple intensely aware of the shape and tangibility of the luminous space itself. Our eyes are drawn upward over the patterns made by the sunken panels, or coffers,in the dome’s ceiling to the light entering the 29-foot-wide ococulus, or round central opening, which illuminates a bril-liant circle again

|

The Panthenon, Rome

Marble veneer and two tiers of richly colored architectural detail conceal the internal brick arches and concrete structure of the 20-foot-thick walls of the rotunda. More than half of the original decoration—a wealth of columns, pilasters, and entablatures—survives. The simple rep-etition of square against circle, established on a large scale by juxta-posing the rectilinear portico against the circular rotunda, is found throughout the building’s ornamentation. The wall is punctuated by seven exedrae (niches)—rectangular alternating with semicir-cular—that originally held statues of gods. The square, boxlike coffers inside the dome, which help lighten the weight of the masonry, may once have contained gilded bronze rosettes or stars suggesting the heavens. |